By Vincent T. Davis,

Originally published by the SAExpress-News on Sep 16, 2024

Baseball myths and legends thrilled the boy. He was drawn to tall tales of hardball hitters, especially a first baseman called “El Oso.”

Folks in Barrio El Azteca, the old Laredo neighborhood, gave Ismael Montalvo the nickname because he was hairy as a grizzly bear.

El Oso was rumored to shave his wrists, neck and chest each day just to go out in public. Some said that when he walked barefoot, he didn’t leave a human footprint.

J. Gilberto Quezada grew up in Laredo and his appreciation of the sport grew as he spent time with his grandfather, an avid fan and umpire in the Mexican League. The boy looked forward to the days his abuelo took him to Washington Park to see Montalvo play with the hometown team, the Laredo Apaches.

As a teen, on Friday nights, he’d watch the weekly ritual of Lucha Libre on his family’s black and white television, his adrenaline rising with the lightning-fast moves of masked wrestlers launching themselves across the canvas. His mother waved her arms and cheered favorite luchadores who included “El Santo” and “Blue Demon.”

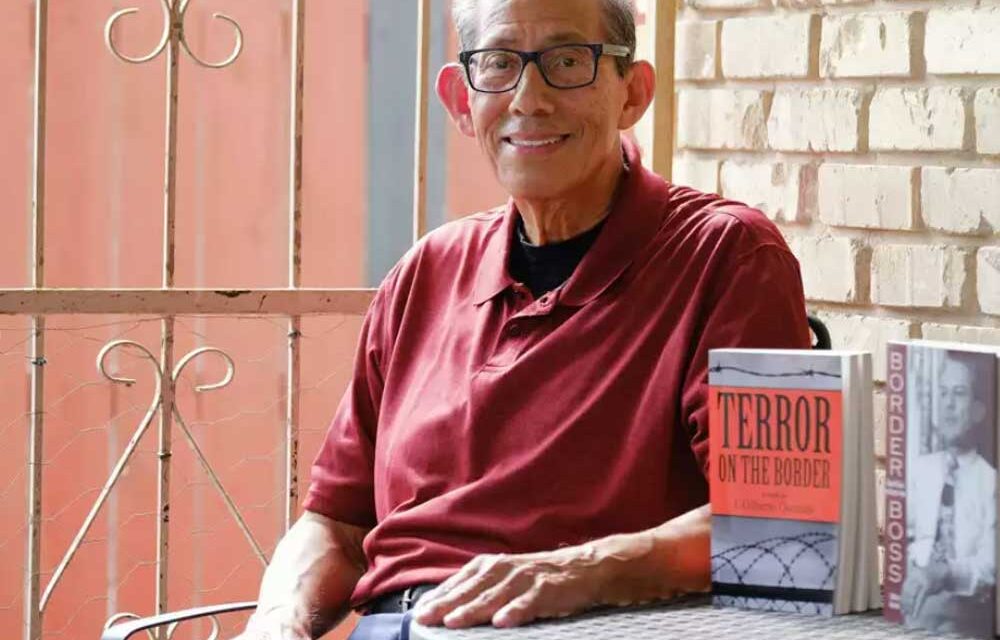

As he grew, Quezada used his love of words to log the exploits of sports heroes, life experiences and the Mexican culture that colored his world.

“I love to write,” Quezada, 77, said during a recent phone call. “It helps my mind.”

The retired educator and historian lives with his wife of 53 years, Jo Emma Bravo Quezada. He has shared essays and poems in blogs, magazines and personal correspondence. He wrote a well-regarded biography of a longtime South Texas political ally of then-U.S. Sen. Lyndon Johnson called “Border Boss: Manuel B. Bravo and Zapata County.” And he’s the author of a novel, “Terror on the Border.”

And for several years, Quezada has kept up a regular commentary in the California-based online magazine, Somos Primos (We are Cousins).

Moved by the passing of baseball legend Willie Mays on June 18, Quezada shared his lifelong love for the game with colleague and columnist Elaine Ayala, who introduced me to his essays.

I learned that his writing, on topics ranging across religion and politics, became a constant stream after he retired as a South San Antonio Independent School District associate superintendent in 2002.

Quezada wrote of Louis Cousins, a neighbor he learned had ties to the civil rights movement. In 1959, Cousins became the first Black student at all-white Maury High School in Norfolk, Va., enduring jeers from a crowd as he walked with his mother up the steps into the campus auditorium. A black and white photo shows Cousins sitting alone in one of the rows up front — the white students seated far behind him.

“I was not going to sit in the back anymore because I finally had an opportunity to be in the front,” Quezada recalled Cousins said.

The retired educator learned Cousins was a military veteran and, like him, a St. Mary’s University alumnus. They began meeting for breakfast to talk about their lives and literature. When Cousins unexpectedly passed away on Jan. 17, 2020, Quezada received the news in a call from his friend’s wife.

“He was an amazing person and well read on a variety of topics,” Quezada wrote. “I do miss his friendship. May his soul rest in peace.”

Many essays express his love of baseball. In 1952, Quezada started collecting baseball cards to see if the major leagues had Latinos on team rosters. He frequented mom-and-pop grocery stores in the barrio, scouring shelves for packs of cards with a slab of bubble gum, all for a penny. He’d sift through stacks and marvel over stats of his heroes. Classmates would stop by his house to trade doubles of cards of players from Cuba, Laredo and Mexico.

Quezada’s appreciation of athletes extended to basketball, namely Wilt Chamberlain. One Saturday evening in 1962, hot winds swept the neighborhood as he kept an eye out for his father, who drove a city bus. Each day, he waited at a bus stop to hand his papa a lunch box packed by his mother, receiving a quarter in return. Then Quezada would spend it on a comic, candy and soda at the Cardenas News Stand a few feet away.

That day, headlines on a San Antonio paper upended his routine — the night before, Chamberlain had scored 100 points as the Philadelphia Warriors beat the New York Knicks 169-147. He bought the paper and added to his treasure chest of sports memorabilia.

Quezada is grateful his mother didn’t toss his collection in the trash when he left Laredo in the fall of 1967 to attend St. Mary’s. On April 4, 1968, Quezada was studying in his dorm room at Charles Francis Hall when his roommate burst in, shouting that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Quezada closed his books and the two walked to Assumption Chapel, which was rapidly filling with students praying for the slain leader.

Quezada wrote his master’s thesis about Father Carmelo A. Tranchese, recognized for helping bring federal housing projects to San Antonio. Standing 5 feet, 8 inches tall, his parishioners called him El Padrecito, the little father.

He learned Spanish from his parents, both from Mexico, but when he was 4, his mother sent him to learn English from a retired teacher in the neighborhood. Quezada developed his love for reading and writing in a bedroom converted to a classroom, nurtured at St. Augustine Elementary School by Sister Mary Emmanuel.

The nun taught Quezada and classmates to quickly express thoughts, sending eight students to the blackboard to write on a topic for five minutes. All the kids had to write. The students would critique their work. By eighth grade Quezada got an A-plus grade on a 10-page assignment — a memoir dedicated to his parents.

Quezada was a junior at St. Augustine High School when he worked with Montalvo, his childhood legend. El Oso hired Quezada, who looked older than his age, to bartend at American Legion Post 59 after school and weekends.

And so the lifelong fan found himself in the presence of his idol. Quezada confirmed that large tufts of hair did indeed sprout from the former baseball player’s body. In a twist of fate, Montalvo bestowed his own nickname to the tall and lanky Quezada, the sobriquet “La Sorga.”

Without fame, recognition or popularity, the young sports fan had landed in the pantheon of pseudonyms — a space reserved for giants of the game.

Photo Caption: Retired educator J. Gilberto Quezada outside his home Friday with two of his published works, a novel and a biography of Manuel Bravo, a midcentury Zapata County politico.

Photo by Clint Datchuk