By Dr. Ricardo Romo

When I returned to Texas in January 1980 after a 13 year hiatus, I found my hometown of San Antonio undergoing monumental political transformations and subtle social and cultural changes.

Every town and city in America experienced change over the latter part of the 20th century. Some more than others. A quarter century after WWII, while the Alamo city was undergoing changes it was trailing significantly behind Houston and Dallas in improving its economic footing as these other Texas cities surged ahead in population, skilled jobs, and overall wealth. Community leaders such as Henry Cisneros and Ernesto Cortes

vowed to alter the slow pace of urban improvements. This is an account of how they accomplished their goals.

Community Empowerment

Numerous Latino political change agents emerged in the mid 1970s in San Antonio who merit attention. The account of Westside resident Ernesto Cortes is central to understanding how political change came about.

Cortes, a Central Catholic High School graduate, earned a degree from Texas A&M at age 19. He enrolled in the PhD program in Economics at the University of

Texas at Austin the following year. However, in 1967 he made a monumental decision and joined Cesar Chavez’ efforts to unionize workers in the Rio Grande Valley, a decision that led him to abandon his graduate studies. The Valley farm workers earned less than a dollar an hour and labored in the spring and summer months in sweltering heat with only short breaks for water and food. Although small employment gains were made, nonetheless, Cortes felt that his work was best suited for an urban grassroots movement. Thus he left the Valley to organize the urban poor of San Antonio.

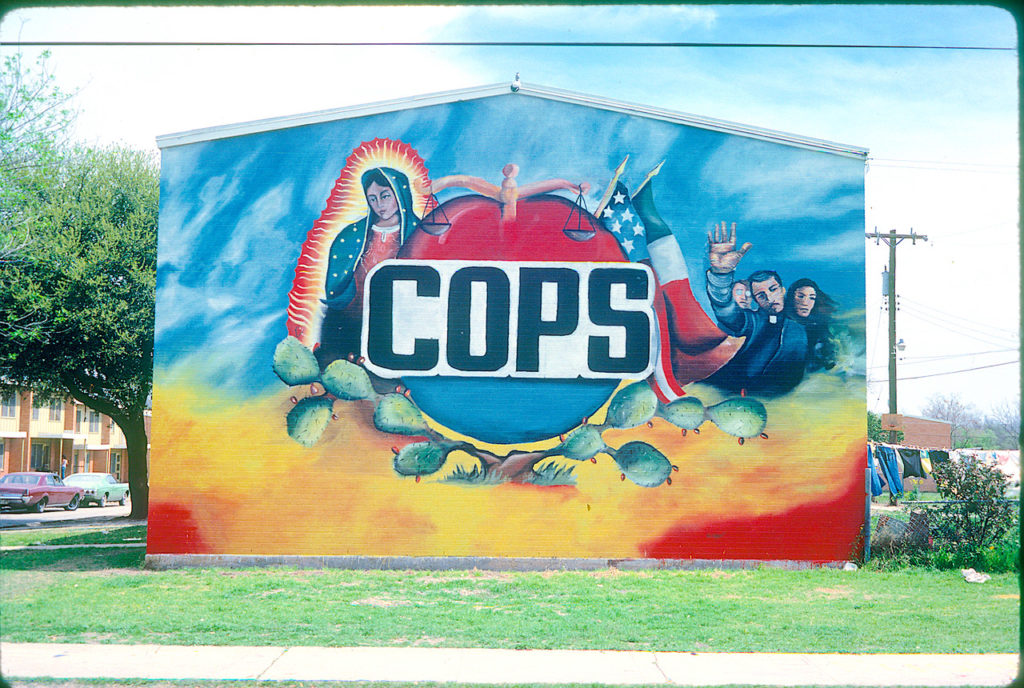

By 1974 Cortes had become a full time community organizer in San Antonio’s Southside and in the Westside low income neighborhoods. He introduced the grassroot concept of “people power” that led to the creation of

Communities Organized for Public Service [COPS].

COPS’ earliest successes came after several crippling floods devastated homes and businesses near the Westside creeks.

In an essay by Moises Sandoval titled “The Decolonization of a City” the author noted that by their

fourth year of existence, COPS drew 6,000 delegates to its annual meeting. While the delegates pressed for

improvements in their communities, they were also demanding higher wages and employment benefits. Sandoval noted that Mexican Americans on average earned $8,000 a year or less, and many subsisted on

income below the $5,500 poverty level. COPS became a powerful voice that criticized the city’s policy of allocating generous tax breaks to industries and companies that paid wages below the national average.

Rising Political Power

When Henry Cisneros entered the San Antonio city council race in 1975, he did so with the endorsement of the Good Government League [GGL] which controlled city politics over nearly a quarter century. Cisneros, also a Central Catholic High School graduate, earned degrees from Texas A&M, Harvard, and George Washington University. When Cisneros first entered politics, COPS had been in existence for only a year and their political muscle had yet to reach full strength.

When Henry Cisneros entered the San Antonio city council race in 1975, he did so with the endorsement of the Good Government League [GGL] which controlled city politics over nearly a quarter century. Cisneros, also a Central Catholic High School graduate, earned degrees from Texas A&M, Harvard, and George Washington University. When Cisneros first entered politics, COPS had been in existence for only a year and their political muscle had yet to reach full strength.

In addition, in 1975, Cisneros ran prior to the creation of single member districts and getting elected meant that he had to run city-wide for his post. The GGL, controlled by wealthy Northsiders, seldom lost an election when they endorsed a candidate. Cisneros won the city-wide election in 1975 and was elected two more times following the implementation of single member districts. By 1981 when he ran for Mayor, Cisneros no longer needed the GGL. He won with strong COPS support, although COPS never officially campaigned for a local candidate.

In the early 1980s COPS and Cisneros were at the peak of their political power. In Cisneros’ run for a second term as Mayor, he won with 94.2 percent of the vote. He won the next two terms with large margins, making him one of the most successful four-term mayors of a major U.S. city. The eighties were also good years for COPS. COPS gained the endorsement of Archbishop Patricio Flores as well as strong financial support from Catholic parishes.

COPS gained a reputation for holding rigorous accountability sessions, which called on political candidates to explain their political goals and visions in short crisp answers. COPS’ leaders, several of whom were ordinary housewives and blue collar workers, were admired by the Latino community and feared by politicians.

As is evident, COPS, which Ernesto Cortes was central to creating, and Mayor Henry Cisneros were the major change agents of the 1970s and 1980s in San Antonio, a remarkable period when a record number of Latinos became politically engaged. Latino engagement contributed to the rise of future young political leaders like Julian and Joaquin Castro, and other Bexar county Latino leaders such as Leticia Van De Putte.

Ricardo Romo

All Photos–credit Romo