The gradual decline of cursive handwriting instruction in elementary schools reflects broader societal shifts towards digital communication. While cursive was once a staple of the curriculum, many schools have phased it out in favor of keyboarding and other technological skills that are deemed more relevant in today’s digital age. As a result, younger generations are growing up with limited exposure to cursive, and many adults also find themselves relying more on emails and texting for communication.

This shift away from cursive has practical implications for both individuals and institutions. For instance, cursive writing offers cognitive benefits, such as improved fine motor skills, memory retention, and literacy. The absence of cursive instruction may deprive students of these benefits, potentially impacting their overall development. Additionally, the lack of cursive proficiency among younger generations means that important historical and personal documents written in cursive could become increasingly difficult to read and interpret.

My own personal experience with cursive is a testament to its enduring value. Mamá was a firm believer in early childhood education, and especially, she wanted me to learn the English language. Consequently, when I was three years old, Mamá enrolled me in the neighborhood schools, “las escuelitas,” that were taught by retired women teachers who turned a room in their house into a classroom. The primary objective was for the students to learn the English language and become proficient at speaking, cursive writing, and reading. Since in those days St. Augustine School did not have pre-kindergarten or kindergarten classes, the escuelitas filled that very important void and quite successfully. The ones I attended before enrolling in the first grade were held during the year and also in the summer. A corollary to the first objective was that we wanted to learn the English language.

Across the street from our house, at the northeast corner of San Pablo Avenue and Iturbide Street, lived the Salazar family, composed of three women, in a two-story brick house. During my visits with Mamá and when I was four years old, Conchita noticed my enthusiasm for reading and decided to open una escuelita. She used an empty one-story, big room with a high ceiling located contiguous to the west side of their house where a colorful mural is now located on the wall facing San Pablo Avenue. And every morning, around eight o’clock, I sat next to her, and she taught me the English language along with science, geography, literature, and arithmetic skills. I can still feel her huge puffy hand over mine as she helped me improve my cursive writing. Doing the writing exercises and reading the children’s books she had at home convinced me that reading and writing are synonymous, that is, a good reader is a good writer and a good writer is a good reader. And this truism has been the cornerstone of my professional and personal life.

Learning cursive at a young age from Conchita and later refining my cursive writing skills at St. Augustine School under the guidance of the nuns has clearly left a lasting impact. For me, cursive is not just a method of writing but a cherished tradition that connects me to my past and enriches my daily life. Whether jotting down notes, drafting essays, or penning articles, cursive remains an integral part of my creative process to this day.

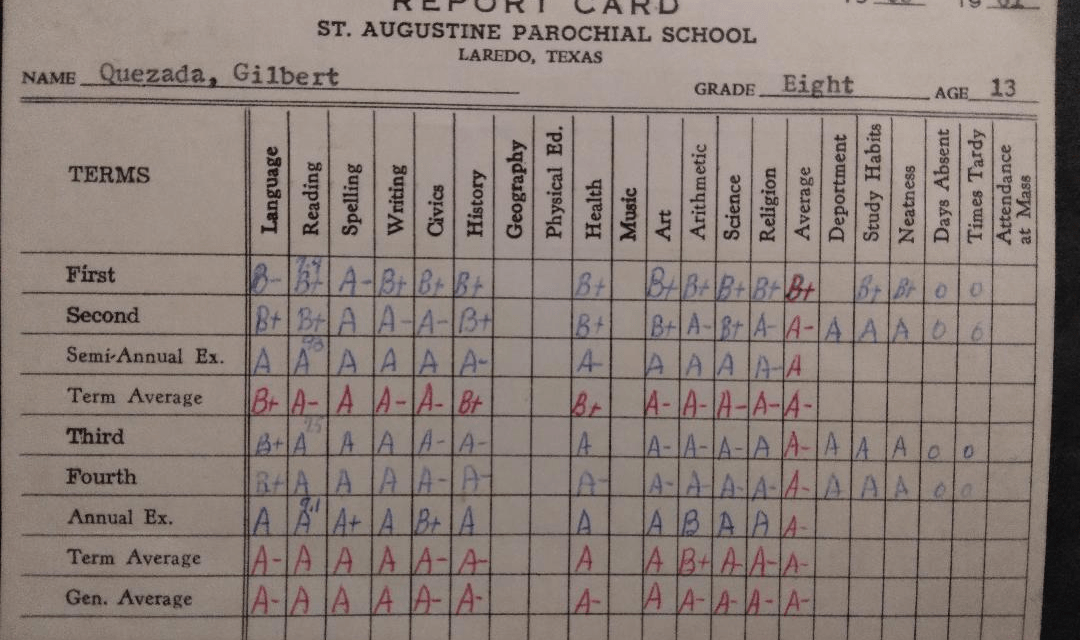

This is my report card when I finished the eighth grade at St. Augustine School, and all the students received a grade for writing, which was cursive.

The situation at the National Archives highlights the growing need for individuals who can read cursive. As fewer people are able to decipher cursive handwriting, the demand for volunteers who possess this skill has increased. The ability to read cursive is now seen as a valuable asset, especially for historical preservation. The staff at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., have even described the ability to read cursive as a “superpower,” emphasizing its importance in understanding and preserving the past.

While the decline of cursive instruction is undeniable, there are efforts to keep this art form alive. Some educators and advocates are pushing for the reintroduction of cursive in school curricula, arguing that it is an essential skill that should not be lost. Additionally, online resources and courses are available for those who wish to learn or improve their cursive writing abilities, ensuring that this tradition can continue to be passed down to future generations.

In conclusion, the shift away from cursive handwriting in schools reflects a broader trend towards digital communication, with significant implications for both individuals and institutions. Your personal experience with cursive underscores its enduring value and the importance of preserving this skill. As the National Archives continue to seek volunteers who can read cursive, it is clear that this “superpower” remains a vital tool for understanding and preserving our history.

You may be interested in reading the following article that was just published in USA Today by Elizabeth Weise by clicking on the following link:

Can you read cursive? It’s a superpower the National Archives is looking for.

And if you can read cursive then you have this superpower talent that the National Archives is interested in you. So, if you are interested in volunteering to read some old historical documents that are written in cursive and are at the National Archives, all that’s required is to: sign up online and then launch in.

Gilberto

P.S. “Family is a little world created by love in a home where memories are made and are cherished for years to come.” by J. Gilberto Quezada

P.P.S. As I get older, I am hoping that one day I will be able to say that I have realized the potential that Almighty God put into me. May God bless you always and fill you with an abundance of good health and may God bless America.