By Isa Fernández

Isa Fernández, MPA is a Legacy Corridor Business Alliance Program Manager at Westside Development Corporation, a freelance photographer and peace and justice advocate.

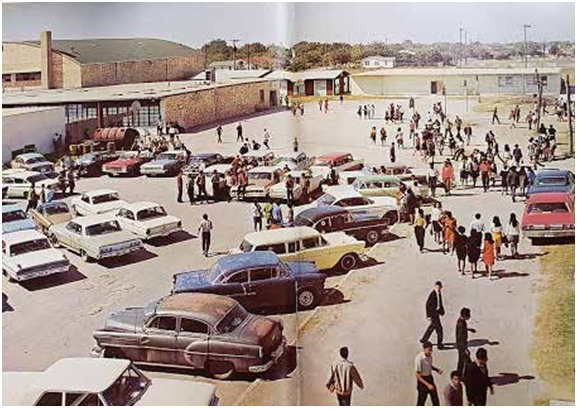

The time was set for nearly 3,000 Edgewood High School students – 9:20 AM on Thurs- day, May 16th, 1968. After months of planning, students would finally walk out of classes to protest the glaring inequalities of the public education system and gain national recognition by arguing public education inequities (due to how Texas public schools are funded in part by property taxes) were robbing them of their future by paving the way into a life of lower-paying employment or endanger their lives through military enlistment. Education and Civil Rights attorney and Edgewood High School alumni David Hinojosa relayed that while most states use approximately 10-20% of property taxes towards education, Texas is 50%, placing the burden on the local tax base to pay for public education. “Property taxes are incredibly disparate, focusing on above and below the ground rather than who is in the classroom,” says Hinojosa. As such, low- income residents experienced dramatic inequities despite Edgewood families paying one of the highest percentages of their income to Bexar county. Their grievances spurred parents to initiate a school finance equity fight that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Rodriguez v. SAISD (1973) and their political activism helped produce a notable generation of activists, educators, scholars and professionals working to promote justice and inspire new generations of activists.

SCHOOL TEMPERATURE

It was true. Students at Edgewood High School in 1968 were living and breathing in dilapidated conditions, freezing in the winter and melting in the summer be- cause the school had no air conditioner. They used outdated books that promoted racial superiority of Anglos. The equipment they used was generations behind. Teachers and counselors would redirect students to lower-level academic courses, avoid sharing information about college and instead encourage them to join the military. Edgewood alumni were dying at a much higher rate during the Vietnam War than any other ethnicity because military recruitment, like today, targeted minority students attending low-income public schools which resulted in the devastating loss of life. “We had lost 54 kids in a 16 square mile per capita was the largest loss in the entire United States, mostly EISD, mostly Edgewood High School graduates,” said Richard Herrera, alumni of Edgewood High School, (Class of ’69, retired Southwestern Bell lineman and current DJ), where nearly 90% of the students in the district were of Mexican origin. So, when a handful of students who had spent time visiting other schools saw what life could be like with functional facilities, new textbooks and educational equipment, they developed a list of eight demands to improve education for themselves and generations that followed by presenting the list of request to the Principal and Vice Principal. The list, abbreviated for publication, is indicated by bold print:

1). Inadequate policing of building and grounds, rest- room supplies: We request more adequate janitorial service than is presently available. Two janitors are inadequate for the area to be kept clean and policed. Many of the restroom facilities lack running water, toilet tissue and/or soap. This deficiency is a health hazard and must be remedied. Plaster in many rooms falls in chunks while classes are in session and heavy rains have caused many leaks which have not been repaired.

Bathrooms were horrible. “It was never clean. If you would walk in your shoes would be sticky. You would go in, and don’t touch anything. The teacher’s bathrooms were locked because they were just for administrators. There was one upstairs for women administrators and teachers. Students said restrooms were locked during class hours, that there was no toilet pa- per,” said Ben Gutierrez, an English teacher and one of the few certified teachers at the time. Gutierrez asked the Vice Principal, “What the hell’s going on? There’s no toilet paper and so he said, “We’re teaching the boys a lesson be- cause they would get the rolls of toilet paper and stuff them down the commode, and then it would all gush out, so now they don’t have a place to go pee” and I said, well, that is not right.”

“We had no air conditioning in that school,” says Richard Herrera. “All the guys carried handkerchiefs. You put them around your neck so you wouldn’t sweat your collar, because we didn’t have a big, large wardrobe.” Teacher Ben Gutierrez shared a striking anecdotal story, “It was freezing. I had my jacket and my gloves, and the principal said, “Gutierrez, take your jacket off, and take your gloves off, and pretend that you’re warm. So, the students can take off their jackets also and don’t complain that it’s below 32. Well at that time, a science teacher said, “Can you come into my room?” Mr. Mangum, he said, the beaker, put the water…look, it’s turning to ice in the classroom.”

Resondo Gutierrez, Class of ’68, who served as Junior Class President (who now is a physical therapist and president of the Edgewood District Veterans, Inc.), explained: “We’re talking about a basic environment, but aside from that, our gymnasium. No shower stalls, and dirty showers giving students zero privacy and athlete’s foot. Facilities were in rundown conditions. Many were missing windowpanes. Replacement of faulty tools in school shops, installation of stair rails and fire extinguishers and extermination of rodents and insects…and we want a gym, not a barn,”

2). Inadequate qualified teachers: Many teachers are not fully qualified to teach the subjects which they have been hired to teach. We re- quest that this inadequacy be remedied…

90% of teachers at Edge- wood were non-degreed and non-certified. Subsequently, they were paid substantially lower salaries than teachers in wealthier districts.

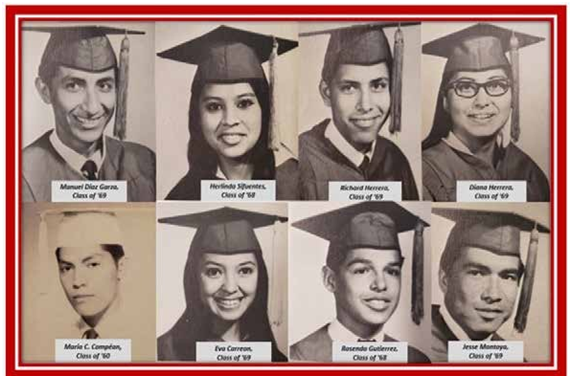

Pictured Left to Right: Richard Herrera, Janie Perez, Richard Garcia, Rosendo Gutierrez, Herlinda Sifuentes, Manuel Diaz Garza, Yolanda Montoya, Mario C. Compéan, Jesse Montoya, Rey Flores, Diana Herrera

3). Inadequate control of monetary records of various clubs and general funds: We request that the monetary records be audited by a com- mittee of qualified parents and administrators and that club monies be entered in the names of the respective clubs for which they have been collected.

4). Inadequate level of academic courses and facilities for teaching: We ask for higher standards with respect to academic courses, as well as a wider variation of such courses to obtain comparability, with those of other schools to better prepare those students planning college study on graduation. Examples are: Chemistry, Physics, Algebra, Computer Programming, Updated Printing and Photography Shops. (An evaluation of present vocational and technical training should be in accord with the technical need for the local community); more speakers on various career opportunities should be engaged. Professional counseling should be made available to all students, as well as counseling on scholarships, loans, grants, and other higher education assistance programs.

Like the great majority of Edgewood’s students, Diana Herrera, Class of ’69 (who would eventually become a 30-year Edgewood Bilingual and Gifted Education teacher, OLLU and UTSA instructor and National Education Association representative) was not viewed as “college material.” Says her husband of 33 years, Richard Herrera – “When Diana went for counseling about going to college, she was told, ‘No, because you’re going to marry Richard and have babies.” When Mario C. Compéan, Class of ’60, (co-founder of MAYO, Texas Raza Unida Party, Committee for Barrio Betterment, Mexican American Unity Council and Centro Cultural Aztlan) expressed interest in going to college after learning about the possibility during an exit student interview, the guidance counselor outright laughed at him. Says Compéan, “I was a good student academically but had no options. I was not aware of any scholarship money. The counselors were no help…. when I found out about it, the next day I was at St. Mary’s campus. (But) when I first met the counselor that’s what he told me: your best option is the military. Sign up for the army.” When he said he wanted to go to college, the counselor “nearly fell out of his chair. He said, quote, “you don’t have what it takes to go to college.” I said, that’s what you think, not me. Very clearly, he said to me, “the best thing for you to do is to join the army.” That’s exactly what he told me.” Herlinda Sifuentes, Class of ’68, (retired business director AT&T and currently Hispanics Inspiring Students’ Performance and Achievement (HISPA) Operations Director and Edgewood Education Foundation president), expressed interest in becoming an engineer and wanted to take Algebra, but was steered to less challenging business math. Rey Flores, Class of ’71 was accused of cheating in math when he was in fact, excelling.

Students received donated, outdated equipment and books from schools with Anglo children. “Inside you sign for your book. The book was first lent out 10 years ago. We noticed we were using old books,” said Richard Herrera. There were manual typewriters, despite the technology being available for electronic. Some Chemistry teachers ordered lab books and chemicals labs, paying out of pocket. “The band wanted uniforms in the correct school colors and instruments that were not hand- me-downs discarded by other school district,” said Manuel Diaz Garza, Class of ‘69 who was active in Student Council and served as a Drum Major (and today is a senior consultant with the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project and Advisory Board Chair of the Alamo Colleges Westside Education and Training Center).

Students who wanted to take advanced classes in order to achieve their potential had to be bused to John F. Kennedy High School, the affluent nearby school at the time where certified teachers taught, classes needed to enter college were available, facilities were up to code and necessary educational materials were current. While some administrators and teachers laughed at the idea of sending Edgewood students to Kennedy for advanced courses, the top five students ended up being from Edgewood High School.

5. Grievance Board: We ask that a committee of faculty members be forced to listen to, investigate and act upon complaints of the student body.

6. Freedom to express views: We request the right to comment upon any school policy or policies felt to be detrimental to the student body without fear of being silenced, ignored or reproved.

7. Student Council to be Voice of Student Body: We request that the Student Council be the voice of the student body (and) no action be taken against any student or any teacher who has taken part in this non-violent student movement for the improvement of school conditions and the betterment of our educational standards.

8. We further and finally request that no action be taken against any student or any teacher who has taken part in this non-violent student movement for the improvement of school conditions and the betterment of our educational standards.

This, of course, wasn’t the case as many students were reprimanded and two teachers who were caught supporting students fired.

Despite “going about it the right way” nothing happened, which opened the gates for the historic walkout. Many attributed this to “how the attitudes that teachers saw us as Mexican American kids in the school…historical class bias. The roots of this take a whole discourse by itself. The set of stereotypes had one goal: to keep us subordinated as a people – politically, economically, socially, culturally,” explained Mario C. Compéan. Student discussions continued. At a subsequent gathering, student Eva Carreon, Class of ’68, (described fondly as “the little girl with the big mouth”) was quoted by her classmates as saying, “You know, we’ve been through this before. We’ve listed all of our requests. We need to do more than bring them up. We need to take the proposals to the right people” A few minutes after she spoke, the Principal who had been listening through the intercom showed up and said, “This convention is dismissed.” So, the students decided to go to the next level and provide the Superintendent with their demands. “Our requests then turned into demands,” said Rosendo, adding, “There are certain human rights that people are entitled to be treated humanely and the students were lacking a lot of stuff and I think intentionally because the surplus books, money, furniture, equipment, degree teachers, certified teachers went to the premier school then, Kennedy.”

STUDENTS WARNED, STUDENTS WALK

Students were clandestine in their plans to go to the Superintendent office, but members of MAYO, who knew the in- justice, showed up and word spread that if “they wouldn’t accept us at the Superintendent’s office, then we’re going to walk there,” says Diaz Garza. This resulted in administrators, teachers and staff warning students who were planning to walk out that they would not graduate if they participated. Likewise, students in sports were got threatened if they walked out, they wouldn’t be on teams the following year. Diana Herrera who was in Ben Gutierrez’s English class, but was unaware of his support recalls being told that she couldn’t walk out because her father worked at Lackland and it “receives federal funds.” Rosendo Gutierrez, along with other senior student leaders, was one of many pulled out of classes and warned person- ally by the principal and registrar, “You know, Rosendo, you’ve really worked very hard to get the scholarships that you’ve earned and we know that you’re one of our schools leaders, but what can you say to your classmates to calm this down?”…Remember – the reason that you have your scholarships is because of the recommendations from your principal and the registrar and the counselors and we can withdraw that at any time and you will not be allowed to graduate or to receive that… And so that really shook me up. And I said well, I can’t do anything. Then I left and then I hear that one by one my other classmates were called in too.” For this reason, many seniors stayed in. “We didn’t know they couldn’t keep us from graduating because we had all our credits, at least I didn’t, at that time.” After attempting to intimidate students from walking out, some teachers tried to stop nearly 3,000 protesting students by barricading the hallways and doors. Rosendo was locked in a classroom by one of his teachers to ensure he didn’t walk out.

When the school’s principal called the police, a group of at least 400 students, with some parents and community leaders, received a police escort as they marched five blocks to district headquarters cheering and carrying signs with messages such as, “Better education now, not tomorrow” and “Everyone in America deserves a good education.” Edgewood walkout alum Manuel Diaz Garza: “San Antonio Policemen were sent to arrest the students, but instead, they formed a protective police line to keep the students safe while crossing Old Highway 90 to the EISD Central Office on 34th Street. Turns out, some of the policemen were graduates of Edgewood High School and veterans that had returned from the War in Vietnam. They were also facing discrimination at the San Antonio Police Department as many of our parents faced discrimination upon return after serving our country during WWII.” Students marched to the district administration office’s main office to speak with the superintendent walking five blocks with a police escort and demanding to speak to Superintendent Bennie Steinhauser, who never emerged. They picked up some students from Escobar Junior High School along the way.

WALKOUT AFTERMATH

Administrators dismissed the protest as the work of out- side agitators such as Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO), (the St. Mary’s University student group the founded by Mario C. Compéan, the late Willie Velasquez, Ernie Cortez, Jose Angel Gutiérrez, Juan Patlan and Ignacio Perez, which would become Texas Raza Unida a political party focused on the needs of Mexican Americans which became prominent throughout Texas and Southern California), that served as consultants to Edgewood students. Both Velasquez and Compéan were Edgewood alumni with tight roots to their community who knew all too well what the younger generation of students was going through. Others additionally blamed Father Henry Casso and Priests Associated for Religious, Educational and Social Rights (PADRES), an organization of Mexican American priests mentoring Edgewood students. By blaming them, administrators attempted to minimize student involvement by suggesting they were “misled as to who their leaders were.” Yet teach- er Ben Gutierrez rightfully gives credit to the students saying, “These guys were the catalyst that gave others the courage to walk out and demand what was fair.” Not that they didn’t use “outside help” to the fullest. With the help of parents, students procured the support of a local attorney who presented their demands to the Edgewood school board a week after the walkout. Board members responded by proposing a school suggestion box. Some improvements were made – namely, restrooms were functional.

And although the subsequent Supreme Court case on the issue of public education inequality raised by brave Edgewood students, Rodri- guez v. SAISD (1973) was unsuccessful due to a conservative court which shockingly declared that education is not a fundamental right, but a privilege, it did help spark the national conversation about education inequality and is considered monumental in Mexican American history. Students were included in a United States Commission on Civil Rights hearing held in December 9-14, 1968 before the Commission on Civil Rights and detailed the inequities for posterity. It helped create Mexican American studies, a new generation of activists and scholars and is referenced in the continuing battle of equal education.

CONTINUING SOLIDARITY & COMMUNITY

After, the “Class of 68, we graduated. We left and we kept looking back…looking to see what’s going to change? What’s going to happen? Our history remains unknown,” says Diaz Garza, adding, “there’s not one plaque” in San Antonio commemorating their participation in the walkouts, which is considered monumental in education civil rights history. Edgewood High School closed campus in 1998 after a bond was passed to renovate the high school. Alumni were shocked to find that their school would instead be transformed into the Edge- wood High School Fine Arts Academy. The ISD didn’t make any special attempt to safeguard what many believe are Mexican American historical artifacts, letting the school be gutted.

Yet more than 50 years after the walkouts, student, faculty alumni and supporting groups like MAYO are still a tight knit group fighting for political, economic and social change, working together to plan the first national conference on the walkout to be held in November. “We still network with each other, we still talk to each other and you know, it’s important,” reiterates Diaz Garza. “I see a path to the future, but it does have to engage students. One of the things that I see that is very positive in what’s happened lately is Mexican American Studies and so to me, that’s one methodology to do organizing. Not only just to learn about cultural and social implications of what has done but do a transformation politically. We didn’t have this. We were asking for Chicano Studies. We had very few models of what we wanted or to be included. To me, this is one of the best routes or vehicles to be inclusive of younger people in high school, even elementary,” says Diaz Garza. “It’s very important that younger people get involved. On the one hand, it’s all about resources. Right now, because of what we did, partly, the current policies we’re seeing from the government, especially the state and national…those policies are directly…the goal is to undo everything we did. They’ve already been very successful. The question then becomes, who’s going to stop them? So, the younger people need to do it. Do they want to organize another Raza Unida or an- other MAYO? If not, what is it they want to organize? How are they going to tackle these problems? Because all of these policies are intended to keep us out of power, which means we won’t have resources. Which means there won’t be any opportunity, so if these younger people want opportunities, they need to start to get active, to make sure they are protecting their interests, fighting for their communities. Whatever is left in us, as elders, we have to make sure that somehow, that huge population gets the word. That they need to get active” says Compéan.

Join the National Chicano Student Walkouts Conference taking place on November 20-23, 2019, in San Antonio, Texas. For more information, please visit https://chicano- historytx.org/ncmsw-confer- ence/.

The author would like to thank Manuel Diaz Garza for his exten- sive help with this living history piece and his continued dedication to peace and justice and helping others.