In 1925, Calvin Coolidge took office as president, F. Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby, the Scopes trial was in the daily news, and Chrysler started producing cars. The Jazz Age continued throughout the Roaring Twenties as New York pulled ahead of London to become the largest city in the world.

Mexico was in the midst of the Cristero War in 1925. La Cristiada, the last major peasant uprising following the end of the Mexican Revolution, was a widespread struggle against the anti-Catholic policies of the Mexican government. The diaspora throughout Mexico caused wave after wave of insurgent activists to swarm through the country, pushing people south or north.

In Texas, oil replaced agriculture and lumber as the major industry in 1925. Immigration from Mexico – and the opening of new irrigation projects – spurred the development of large fruit and truck farming areas. “Ma” Ferguson, Texas’ first woman governor, opposed the Ku Klux Klan, fought against new liquor legislation, and pushed for extensive cuts in state appropriations.

The Gilded Age continued to boom in San Antonio with the construction of Classical Revival, Tudor, Spanish Eclectic, Queen Anne, and Craftsman style houses throughout the city. The Southwest Insane Asylum changed its name to the San Antonio State Hospital in 1925. And the San Antonio Junior College was formed, precursor of today’s Alamo Colleges.

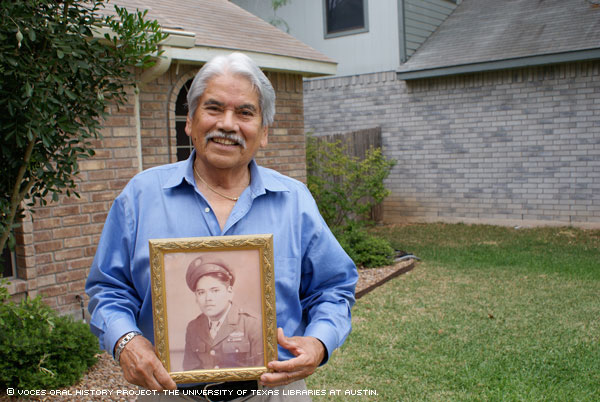

Also in 1925, Juan Mejía was born on September 13 in San Antonio. His parents, Cecilia Rosales Cepeda (a homemaker from Zacatecas) and Pedro Mejía (a waiter and baker from Guanajuato) had come to the United States during the Mexican Revolution. The family eventually had ten children, five of whom served in the U.S. military.

Juan grew up in the Great Depression, a period of poverty for millions across the United States. But because of the blatant discrimination against Mexican immigrants, it was even worse for the Mejía family.

Juan attended elementary school in Thorndale, a Texas town about 40 miles northeast of Austin, and helped his parents before and after classes. In the early 1930s, Juan would serve as a translator for his family’s business transactions. Farm labor sometimes meant the family had to travel to West Texas and the Midwest to find work.

But then, at a time when people were lucky to earn ten cents an hour, his dad got a good job with the Works Progress Administration. It paid $2.50 a day.

“After my father started working for the WPA, we ate better; we lived better, and our lives changed more than anything after World War II,” Juan recalled in a 2011 interview, “because then we all had work.”

Even though the Mejía family lived on a hardscrabble Texas ranch in the 1930s, intervening years have tempered the memories of those days.

“My childhood was beautiful,” Juan later recalled. “We just worked and played with things around the ranch. There were always lots of activities… My mother took great care of us and encouraged us to go to school.”

His appreciation for thriftiness and his strong work ethic were forged during these hard times. But for Juan, times were about to get a little rougher.

In 1943, shortly after his 18th birthday – before he graduated from high school – Juan enlisted to serve in World War Two. He later recalled his experiences in an interview with Laura Barberena.

“I wanted to go into the Army,” he said, “to be able to get to know other people and get to know everything. I was very happy. We all wanted to serve our country, all of us.”

He was sent to Camp Shelby in Mississippi for training and then to Massachusetts for transport to Europe. The RMS Aquitania, a 30-year-old British ship, moved American troops to Scotland. It was no longer a cruise ship in the Cunard Line. Sleeping quarters were cramped and the food was awful.

“The coffee was real bad, real bad,” Juan said. “For breakfast they gave us wieners.”

Their reception in England raised the moral of the troops. They would need it. The Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front, was just on the horizon. And the American forces took the worst of it, incurring the highest casualties of any operation during the war.

“The Germans came with all their artillery and with everything they had, airplanes and everything,” Juan recalled. “I saw my friends on the ground, dead. They killed my lieutenant. The last time I saw my commander, he had a shot here in his throat, and there was a chaplain, kneeling, giving him his last rites.”

Frank Trejo wrote in an oral history project that Juan and his unit had dug their Continued

foxholes when the captain told the men to rest before heading out again. When Juan woke up, he was alone.

“I just got up and went that-away – and went and went and went – until I heard a voice speaking English; and they were also lost.”

Juan said his whereabouts were unknown for about ten hours. His mother received a telegram that he was missing in action. A month later she got another telegram that Juan was hospitalized somewhere in Europe.

Juan was sent to Belgium to recuperate from exposure to the cold and damp. And that’s when a bomb went off. But Juan said it never occurred to him that he might die.

“The closest I got was when a piece of shrapnel fell on me here on my coat,” he recalled 66 years later. “I just did this, brushed it off.”

For his service, Juan received the European Theater of Operations Medal (for military duty during WWII), the Combat Infantryman Badge (in recognition of his risk and sacrifice), and the Good Conduct Medal (for his years of honorable and faithful service). More than five decades after the war, Juan was presented the Bronze Star. This award is presented for heroic service and meritorious achievement in the face of combat.

But one of Juan’s proudest achievements was when he earned his high school equivalency diploma in 1972 – almost 30 years after his education was interrupted.

After the war, Juan traded his military service for a job with the civil service.

“World War II opened doors for me,” Juan said, “to be able to work for the government because I didn’t have enough schooling, even though I didn’t have experience.”

He worked at Kelly Air Force Base for the next 34 years. Along the way, Juan married Enedina R. Mejía and raised eight children. His oldest daughter, Berta, went to law school and became a first assistant city attorney in Houston, before being appointed as a judge.

Other children include Rose, Virginia, Grace, Cecilia, Johnny, Arturo, and Gina. Arturo, a police detective in Houston, accompanied Juan on a trip to Europe in 2016.

“We visited the battlefields where he fought and paid homage at the cemetery where his comrades rest,” Arturo said. “It was very cathartic for him and an education for me. I never knew those parts of my dad’s life.”

After retirement from Kelly Field, Juan utilized his hardscrabble education from the Great Depression. Mejía Lawn Service indulged Juan’s green thumb and served as a first job to his many grandchildren. This allowed him to instill in his family of destiny a strong work ethic and sense of pride – attributes he inherited as a legacy from his parents.

A few weeks before his death, Juan was honored at Minute Maid Park in Houston for being a proud member of the Greatest Generation. The Houston Astros and thousands of baseball fans gave him a standing ovation. This Labor Day celebration was a fitting tribute to pay homage to a veteran on the weekend of his 93rd birthday.

Ever active and independent, Juan was killed as he rolled his wheelchair across a street on September 29, 2018. His death was preceded by his wife in 2006.

But he felt he led a blessed life. In looking back, he urged Latinos never to forget their culture.

“Always hold your head up high, and be proud of being Latino,” he said in 2011. “And serve your country when you are called.”

Juan Mejía A Veteran’s Day Tribute