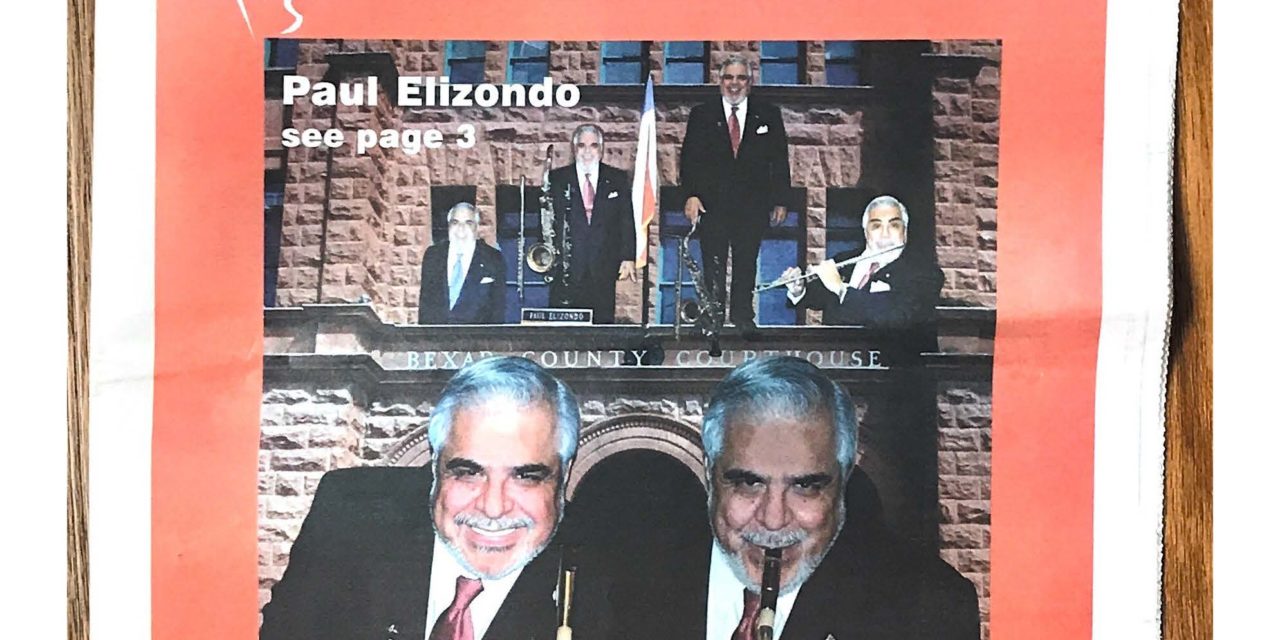

This article was published October 21, 2001 in La Prensa when Paul Elizondo was still performing in jazz festivals and as part of the San Antonio Jazz Orchestra. Rest in Peace Commissioner.

Paul Elizondo belongs to a very special breed of musicians.

“Our goal has always been to have a very special and diverse group. One that can play anything and fit anywhere because Hispanics are not a one-dimensional people,” Elizondo said during an exclusive interview at his office.

“Our motto is ‘music at it’s best.’ We Texicans have many kinds of music in our roots so it’s very important that we sustain and nurture all of our musical heritage.”

Most importantly, Elizondo is one of the few pioneers who continues to perform. Couple that with his record as a public servant and he stands out above many of his musical peers. You see, the silver haired musician wears two hats.

During the week, he is a pillar of strength, unrelenting, firm and fierce in executing his administrative and executive responsibilities as a county commissioner. But come Friday evening, he slips out the side door of the Bexar County Courthouse and becomes a mild mannered musician who plays flute, clarinet, alto, tenor and baritone saxophones.

As one of the few remaining musical pioneers, he toots his many horns as the Alamo City’s “Pied Piper of the Big Band Sound.”

As a public servant, the San Antonio native served in the United States Marine Corps ( 1957 – 1959) and as a teacher/administrator(1960-1978). He spent 14 of those years in the Edgewood School District and the remainder as a band director and artist-in-residence with the San Antonio Independent School District.

After serving two terms as a Texas State Representative for District 57-1 ( 1979- 1982). He was elected Bexar County Commissioner for Precinct Two, a position to which he has been continuously re-elected since 1982.

As a result, most people are more familiar with his public record as an elected official than his vinyl records. Therefore, this article will touch on Elizondo’s musical career. which spans to over half a century. It is also a fact that the musicians in his family date back much before that.

“My grandfather, Paz Elizondo, played accordion and other relatives played violin and guitar where they lived as sharecroppers with Germans and Bohemians en un rancho in Dryer, Texas,” he said.

It was here that Paz, who spoke what little English he knew with a German accent, picked up the accordion and learned to play polkas, redovas, Shottises, corridos and valses for family gatherings. It was also here where Paul Elizondo Sr. was born and reared before moving to San Antonio.

“Unlike my uncles, my father who was 6-feet-2-inches tall, played saxophone and clarinet and It was from his love for jazz, blues and the big band sound that I developed my taste, primarily for American and Mexican big band music while my cousins played conjunto music.”

“However, my father did admire good accordion players. This was before drums and later the electric bass were incorporated into conjunto music. As a result, I learned to appreciate all types of music.’’ Elizondo continued.

“When he came to San Antonio, my father made his living as a barber. As a hobby, my father studied electronics during and after World War II. After a long hospitalization for tuberculosis, he went to work al Kelly Field.

“At home, he built his own homemade amplifiers and speaker cabinets. Next, he connected a record player and microphone to this system and became one of the first deejays for parties. He was not a professional musician, but he performed a valuable musical service both by the music he selected and for his unique announcing style,” the commissioner recalled.

These were the earliest influences and musical seeds planted in Paul Elizondo Jr.’s heart as a child. However. they did not begin to sprout until 1950, when the then 15-year-old enrolled in band at Central Catholic High School. He wanted to play the trombone, but he was 4-feet-8-inches tall and his arm could not stretch the slide out far enough, so he wound up learning to play alto saxophone, later followed by the larger tenor and baritone saxophones.

By December, he had learned to play well enough to participate in a Christmas concert. His grandfather, who had now retired and moved to San Antonio, was very proud of the grandson he would often tell, ‘’I’m not going to teach you to play accordion porque mijo no va hacer músico lírico, el va a saber tocar por nota. My grandson is not going to play by ear, he is going to learn to play by note.”

During the early ‘50s, first Ramiro Cervera, and later Johnny Sarro, both who graduated from Lanier High School had already formed their own orchestras, as had Central alumnus Richard Cortez. It was an era when most high schools sported student generated dance bands formed by enterprising young band members, and Elizondo joined Central’s Melodeers plus Sarro and Cortez’s bands.

“It wasn’t hard getting gigs because kids usually made $4.50 per night,” he said with a laugh, “Besides, orchestras here were also well received by the Anglo community because of our military bases. We had to be sharp to successfully compete with Hispanic, Anglo and service bands.’’

It was also around this time frame that Master musicians, who had studied in Mexico’s conservatorio de musica came to this country. Among these were Juan Garcia Esquivel and Mateo Camargo. Esquivel went on to achieve international fame just as “Esquivel” for being the first to use voices long before Ray Conniff, and for his eclectic musical arrangements, which led them to quickly become a mainstay of the Las Vegas lounge circuit.

“San Antonio became a musical magnet,” the county commissioner said. “In fact, all of those musicians moved here because the demand was not so much for ethnic music, before music of the era. Thus, San Antonio developed a highly skilled caliber of musicians.”

Because of the insecurity that comes with the life of a musician, some of these talented musical masters chose to get full-time job to support and provide for their families. One of these gentlemen was Gilberto Murillo, a machinist at Kelly Air Force Base and one of the senior Elizondo’s colleagues. In respect to his friendship with Elizondo Sr, the Mexican music maestro agreed to give Paul Jr saxophone lessons.

“Quietly demanding, he was an inspiration and I learned enough music theory and harmony from him to get a music scholarship and to keep from having to crack a book in college for a couple of years up until I had to study counterpoint,” Elizondo recalled.

When Elizondo graduated from Central Catholic High School in 1953, he was offered several academic scholarships. Among those was the first LULAC scholarship to major in law. My parents were very disappointed when I turn down those scholarships. She wanted me to be a lawyer. He wanted me to be an engineer. Instead, I join the professional musicians union and accepted a music scholarship to St Mary’s University.

Between 1952 and 1954, Elizondo played all the saxophones, clarinet and flute with Jesse Gonzalez, Emilio Caceres, Eduardo Martinez and Gilbert Fierros orchestras. He also played with Fatz Gonzalez and The Harmoneers. “But the top man was Jesse Gonzalez because of his personal, sophisticated and hip arrangements and the band’s musicianship,” Elizondo added.

Johnny Esquivel, Jesse Gonzalez, Johnny Rodriguez, Gilbert Fierros and Cruz Arizmendi all had college degrees and it was these top notch, well-educated musicians, who inspired Elizondo’s generation to enter the Public School teaching profession.

It was during this time that then close- shaved and clean cut, baby-faced college student sported horn-rimmed glasses . “They were cool and they were in style, besides I had a slight astigmatism of the eye because I was doing a lot of reading and a lot of studying,” he explained.

Turning the interview back to the bands, Elizondo said, “ I was hired by all of them because I was a utility sax player. That means I could play all the saxophones and fill any chair in the second section of these bands. Few people owned televisions sets so the best entertainment was to go out and dance boleros, swing, polkas and Latin rhythms like the suby, porro, danzon, rhumba, mambo and cha cha cha.

“I was ambitious and part of the young and the restless. I wouldn’t think twice about carrying all these saxes, plus a clarinet and flute on the bus from my home on 402 E. Lubbock Street on the south side to any gig. Afterwards, I would get a ride home with one of the musicians.

There were lots of bands and therefore lots of opportunities to perform. That’s the advantage of knowing how to read music. That’s also one of the reasons my grandfather wanted me to learn how to read notes. I’m glad my father got to see me play with the symphony and conduct my own band.

However that didn’t mean big bucks. I found that out during gigs in Albuquerque, New Mexico when a 14- piece band alternated with Paulino Bernal. His 4-Piece conjunto made more money than we did. He got paid $8,000 while our band went for about $1,500. Hell, we were reading music but the guys playing by ear were the ones making the money. So I wonder where I would be and what I would be making if I had learned to play the accordion.”

“While I was raised more into the sounds of Coleman Hawkins,Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Duke Ellington, who is Jordan, Count Basie and others of the legendary era. I also find out how popular our own homegrown tejano orchestras were outside of Texas.

“I found out how big Beto Villa was when I was saw his portrait alongside all my musical heroes as one of the band leaders who had filled up his Montana State Dancehall.”

There’s a Mexican saying that says ‘El musico se hace en el teatro’ (the musician is created in the theater). Taking this into account, Elizondo became part of the theater orchestras at the Alameda, Nacional and Empire Theatres. With them he backed up Agustín Lara, Libertad Lamarque, Toña La Negra, Pedro Vargas, Cecilia Cruz Manolo, Alejandro Alvarado, Los Hermanas Navarro and many other stars.

Later his own band should have stayed with Pablo Beltran Ruiz, Paris Prado La Sonora Santanera, Tito Puente, El Gran Combo, Mike Laure, the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, the Airmen of Note, Mariano Merceron, Vicente Fernandez and Juan Gabriel, when he was a rock and roller.

On top of playing with so many bands, Elizondo also made extra money as a studio musician for James Wolf’s Riol and Tom Tanner’s TNT record labels.

Therefore Elizondo’s signature saxophone sound can be heard on countless Tejano music records. In addition, he also composed and recorded many of his own Tunes as 45 RPM singles.

“Chili bean,” “Surfside” and “Monkey Time” (Domar Records) are three of these compositions. Then there were his recordings of “Chivarico”, “Jugo de Pina,” “Tu Boquita de Flor,” and “Me Cai De La Nube” for UAR Records.

As a sideman, Elizondo backed up for different vocalist like Ramiro Cervera- Javier Chapa, Val Martinez and Adaline Salas-Cuesta. He also backed up Salvador Rubio on “Mi Ultimo Refugio” as a part of Lalo Ruiz’s Orchestra.

Ruiz and Martinez both moved to Los Angeles meanwhile the Saint Mary University Music major also freelanced with Tex Beneke, Al Sturchio, Bobby Brown, Lee Castle, Pete Brewer, John Launer, Rudy Carr and the Bobby Galvan orchestras because as he stated he was a ‘utility musician’ and available.’

Elizondo also toured with Russ Gary, Chuck Cabot, Henry King, Buddy Brock and Ed Gerlach orchestra’s. This means his experience range from proms, wedding, rodeos, circuses, ice capades, night clubs and dinner clubs to fancy country clubs and concert stages from the Mexican border to the Canadian border and to the Far East.

Immediately upon graduating from St Mary’s University in 1957. Elizondo joined the U.S. Army Corps, got rid of the glasses, grew a matinee Idol type mustache, went through all the infantry training and emerged as a mature looking young man.

He was ultimately assigned to the Marine Corps Depot Band in San Diego California and the 1st Marine Air Wing Band in Iwakuni, Japan. This meant touring Hong Kong Taiwan, Burma and the rest of the Far East. Returning to San Antonio on October 31st 1959, Elizondo sat in with Bobby Galvan orchestra that same night.

“I went on to play with Arturo Lopez, John Esquivel, Roberto Chavez, Arnulfo Garcia and Eugenio J Nolasco orchestras. Felix Solis plus Ramiro’s Cervera also had top bands at the time,” Elizondo said.

Thanks to Manuel Leal who worked at KUKA, in 1961 Elizondo,Jacinto Guzman, Julio Dominguez and other local musicians joined the Luis Arcaraz Orchestra and off they went on a stateside tour. Louis and Victor Reyes and Corpus Christi trombonist Joe Gallardo and other Texas musicians formed part of a later edition of this famous International band.

Later, these musicians subbed and doubled up with Beto Villa, who opened for Arcaraz.

“I remember we would sit in with Beto Villa then we would run backstage, change coats and come back out as Luis Alcaraz’s band. Little did the people realize we were the same musicians! It was very challenging to say the least.”

Asked to compare these famous Pioneers, Elizondo said, “ Beto Villa had lots of persona. Arcaraz more profound, more refined. Eduardo Martinez didn’t play but he was very charming, and Emilio Caceres was the best musician; he was a genius. He would often improvise strike a certain chord he liked and start to compose on the spot . Often while the band and the public were waiting for the next tune to begin.

By 1963, Galvan had gone into the music store business in Corpus and hung up his baton. Solis was long established and many sidemen urged Elizondo to form his own orchestra. The feasibility became more apparent after a super successful gig he put together at the last minute with a makeshift handful of San Antonio musicians from other bands.

“In 1967, we hit the mark when we learned to play for the people instead of playing for ourselves,” the commissioner said. Some of the Social Clubs were not too pleased with our new repertoire but slowly I learn to read people and play for their taste.

My band became a reflection of the city amalgamation of cultural styles and social mores,” Elizondo explained.

When asked what is your secret, “I can summarize that in one word- Quality!” Elizondo said with great pride. “You’re going to hear good musicians play good music. We concentrate on having a full Dance Floor. Therefore, we gauge ourselves by the number of dancers and the applause. We play to people from all walks of life. We like to brag that we will play and please both your grandmother and your granddaughter.”