By Dr. Ricardo Romo

The Culebra Street corridor is the only community on the Westside where for over a half a century (1930-1980) Latinos, Blacks and Anglos lived in close proximity.

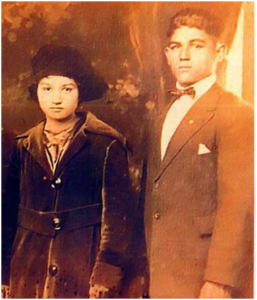

In the last fifty years the community has changed dramatically in terms of racial and ethnic mix, but the diverse history of the neighborhood is important. My mother, Alicia Saenz, grew up just south of Culebra Street and lived on Leal and Ruiz during the period 1930-1945.

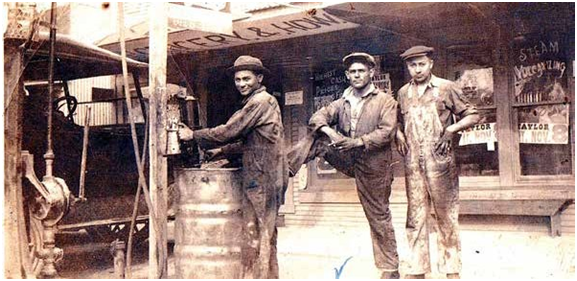

Her dad, Jose Maria Saenz, lived on Ruiz most of his life, two blocks from his son Jesus Saenz, who worked for the railroad and as a garage mechanic before starting his own company, Saenz Electric. My mom’s sister, Frances Gonza- lez, lived four houses from their dad’s house.

My grandfather’s eldest son, Jesus Saenz, and his wife joined the Virgil Elizondo family as caretakers of Christ The King church on Leal Street. The Elizondos had a grocery store across the street from the church which was less than fifty yards from their home. Virgil Elizondo, who became a Catholic priest in the 1960s, went on to head San Fernando Cathedral. He also taught reli- gion for many years at Notre Dame University. I recall going to watch movies in the Christ The King church yards. Along a tall church wall priests and nuns hung a large bed sheet and used a movie projector to show Mexican movies.

My grandfather’s eldest son, Jesus Saenz, and his wife joined the Virgil Elizondo family as caretakers of Christ The King church on Leal Street. The Elizondos had a grocery store across the street from the church which was less than fifty yards from their home. Virgil Elizondo, who became a Catholic priest in the 1960s, went on to head San Fernando Cathedral. He also taught reli- gion for many years at Notre Dame University. I recall going to watch movies in the Christ The King church yards. Along a tall church wall priests and nuns hung a large bed sheet and used a movie projector to show Mexican movies.

However, before 1970, few Latinos lived north of Culebra. It was the old Northside. The neighborhood’s two schools, Horace Mann Middle School and Jefferson High School, enrolled a largely Anglo major- ity student population. Irving Middle School enrolled almost all Mexican American students, and the majority of Latinos from the neighborhood went to Tech High School.

This Culebra Street corridor, which in the 1940-1970 era consisted of a vast area between Culebra on the north and Mar- tin on the south, was bordered by Colorado Street on the eastern section and 36th street on the western side. This area remained largely segregated during this period.

In the pre Richard Nixon era, communities across the south vigorously sought to keep the racial divide or Jim Crow seg- regation in place. In 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court chipped away at segregation when it handed down the Brown vs. Board of Education decision making segregated schools illegal. The civil rights laws of the Lyndon Johnson administration followed, but southern states, Texas included, sought to turn the clock back on racial equality and social justice.

The Culebra Street corridor had a unique feature as a West- side community. Culebra Street was a major thoroughfare, but it also served as the racial and ethnic divide between Anglos and Mexicans in the city. Historian David Montejano, who grew up in the neighborhood south of Culebra Street, has elaborated on the growing ra- cial tensions in that part of the city in the aftermath of the 1954 Brown decision. His essay on this topic appears in this issue of La Prensa Texas. The essay previously appeared in the Texas Observer.

Latinos began to cross to the northern side of Culebra Street in the mid 1950s to attend Horace Mann Middle School which was north of Woodlawn Ave. While my family lived on Monterey Street in the West- side, my parents insisted that my brother Henry and I attend Horace Mann instead of Irving Middle School. Henry and I arrived at Mann in 1956, the second year of the educational integration experiment. Most San Antonio schools were still segregated by residential boundaries for Latinos. Prior to 1954 Blacks attended segregated schools and were restricted from buying property in White neighborhoods. Schools such as Mann were more than 95 percent white until the school boundaries changed in 1955. The integration of San Antonio schools, which began in 1954, allowed students from the barrios to attend high schools out- side of the Westside. In 1955 Horace Mann enrolled students from the Menchaca Courts (all Latinos) for the first time. The housing project, just south of Culebra Street near 24th had previously sent all of its stu- dents to Irving Middle School. In 1956, Horace Mann was over 90 percent Anglo and it seemed to me that less than 50 Latino students were enrolled.

The inclusion of Latino stu- dents from the southern side of Culebra Street at Horace Mann appears to have introduced so- cial integration problems. The Garcia family which lived on Blue Ridge near the Menchaca Courts enrolled their oldest son Jesse at Horace Mann in 1957.

The following year the Garcia family attempted to enroll their younger son Eddie, but were told that the school district boundaries had changed and he would have to attend Irving. The city bus which took us from the Westside to Horace Mann then went on to Jefferson High School. There were no African American students at Mann in the 1950s, but they were permitted to enroll at Jef- ferson High School. Our bus route took us past the Popular and Zarzamora Street intersection where African American students boarded our bus on

their way to Jefferson.

Despite the limited attempts to desegregate San Antonio schools, the ethnic racial communities remained largely segregated. The African American community was concentrated in the area between Ruiz and Culbera, largely near the Zarzamora commercial district, known at that time as Lincoln Heights.

The origins of the African American community in the west end of San Antonio has an interesting history which may be traced to the immediate post Civil War era (post 1865) when Dr. Anthony Michael Dignowity, a physician and Czech immigrant, registered city land sales to Black families.

Dr. Dignowity, who built his home in the area that is now known as Dignowity Hills in the eastside of the city, was an abolitionist according to Everett L. Fly, San Antonio architect and historian. Fly has documented the sale of residential property in San Antonio to African Americans during the second half of the 19th century. By the early 1940s, the African American community was centered in one large neigh- borhood surrounding Lincoln Courts, one of the city’s segregated public housing units. Growing up, I visited my grand- parents often and would spend the evenings playing basketball at Dunbar Middle School. There, on the basketball courts, I met a young Dunbar middle school student by the name of Warren McVea, who became a

Texas football hero.

By the time Warren McVea finished high school, he was the African American community’s most famous resi- dent. Warren McVea lived two blocks from Dunbar Middle School and two blocks from my grandfather’s house. In high school, McVea scored nearly 600 points over three football seasons, including 38 points in a playoff game with Robert E. Lee High School. McVea received 75 scholarship offers, most from out-of-state schools, but McVea’s mother convinced him to stay in Texas. McVea is credited with breaking the color barrier in Texas college football when he enrolled at the University of Houston in 1964. At the University of Houston, McVea set a school record as a runner, receiver and kick return specialist with 3,009 career all- purpose yards. He played in the NFL for six seasons earning a Super Bowl ring in the Kansas City’s Chiefs 23-7 victory over the Minnesota Vikings in 1970. The Culebra neighborhood pro- duced many other well-known San Antonians. Over many years the Culebra corridor was home to Latino businessmen and women, musicians, and politicians, including former San Antonio mayor Ed Garza. Former City Councilwoman Mary Alice Cisneros lived in the Culebra Street corridor on Perez Street. Her parents, Porfirio and Annie Perez, raised nine children on income from a grocery store and bakery. They initially sold groceries out of the house, eventually opening the Perez Grocery Store in the late forties.

In a 2007 Texas Monthly story, Mary Alice told reporter Jan Jarboe Russell: “All nine children worked in the store, which became as famous for its role as a mom-and-pop bank and social service agency as it was for its pan dulce and barbacoa.” Mary Alice told Russell that as a young girl she remembered “helping custom- ers translate their immigration papers, cashing checks marked with an X for neighbors who could not read or write, as well as stacking groceries, waiting on customers, and working the cash register.” She met her fu- ture husband Henry Cisneros at a neighborhood baseball game when she was 12. They married seven years later.

The Culebra corridor community has been losing its diversity over the past 50 years and soon the neighborhood will have almost a total La- tino population. Located in the 78207 zip code area identified as one of the poorest areas of San Antonio, this region now has a public school enrollment that is 97.2 percent Latino.

The African-American population in the Culebra corridor resided largely in the area of Lincoln Courts (Zarzamora to 19th Street) and in the sur- rounding dwellings between Ruiz and Culebra. Drawing from U.S. Census data, it is estimated that African Americans in this community numbered 1,823 in 2014, a decline of five hundred residents from the previous count in 2010.

Most people consider the Westside a Latino community, but the African American residents have an important history in the Westside that should not be overlooked by historians. Moreover, the Culebra Street corridor is one of the culturally rich neighborhoods that has contributed greatly to the social fabric of the city.

Photos from the Dr. Ricardo Romo Family albums.