The San Antonio Museum of Art retrospective, Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, is impressive and a triumph for the museum. This exciting exhibit can be seen in the museum’s large Cowden Gallery from September 20, 2024 through January 12, 2025.

Four decades ago Mesa-Bains introduced the concept of ofrendas [home altars] as a way to retrieve and preserve cultural memory. Ofrendas have been a part of Mexican culture since the 15th-century Spanish colonial years. Over the last 175 years [post U.S.-Mexican War period], Mexican Americans have blended the Indigenous and pre-Spanish colonial ofrendas with modern versions to continue the practice of honoring family, community, and significant Latino/a historical figures such as the Virgen de Guadalupe, Cesar Chavez, and Dolores Huerta.

A native of Northern California, Amalia Mesa-Bains received a Bachelor of Arts degree from San Jose State University in 1966. In the early 1980s, she earned a Master’s and Doctorate in Clinical Psychology. During her early years as an artist, she taught bilingual and ESL classes in the San Francisco School District. She installed her first altar for a Day of the Dead exhibit titled “Five Woman Altar” at San Francisco’s Galeria de la Raza in 1975. During her teaching years, she prepared ofrendas of Frida and Diego [1977] and Homage to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz [1981] two important exhibits illustrating her devotion to feminist subjects.

Art historian Emma Perez, the author of Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities, notes that from the 1980s to the present, Mesa-Bains “has used dress and ‘domesticana’ to explore the spaces of women’s gendered, and transgressive, social and cultural activities in her altar-based installations.” In nearly 50 years of creating art, Mesa-Bains has gained fame for her installations, but her career also includes exhibit curator, author, visual artist, and educator.

Mesa-Bains is recognized as one of the founders of the Chicano Art Movement. She is among the first Chicana artists to create altars and related installations and was among the first Latinas collected by the Smithsonian. Her “Ofrenda for Dolores Del Rio” installed at the Mexican Museum in San Francisco in 1984 and revised [1991] was collected by the Smithsonian American Art Museum as part of the exhibition Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art. Mesa-Bains is a recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship (commonly known as a “genius grant”), the only Chicana visual artist to be recognized with this prestigious award.

“The collection of wondrous objects in the Mesa-Bains’ installations,” notes art scholar Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, “transmit knowledge and learning together with the spirit of enchantment.” Ybarra-Frausto’s book Amalia Mesa-Bains: Rituals of Memory, Migration, and Cultural Space is a superb introduction to her work. Ybarra-Frausto suggests “The artist’s lived mestiza experience is an essential element of her artistic practice.” Ybarra-Frausto credits Mesa-Bains with uncovering and reclaiming “women-centered knowledge systems, artistic practices, and forms of expressive culture that have sustained group identity, historical memory, and solidarity with feminist struggles worldwide.”

As an artist, Mesa-Bains has evolved over forty years of creative activity. Her start as an artist in the late 1960s and early 1970s coincided with the early years of the worldwide peace movement and international calls for social justice. She recalls that her “practice formed within a model of justice, cultural reclamation, and community commitment, while my family history and the history of my community have provided me with purpose and direction.”

Like the Renaissance artists of the 15th century, Mesa-Bains brings wide-ranging knowledge to her creative work. Her treatment of universal themes of life, death, family, migration, womanhood, healing, and resiliency found in her installations reveals her training as an artist, educator, psychologist, cultural interpreter, curator, and activist. Her understanding of Mexican and Mexican-American culture is also formed by years of study of five centuries of Indigenous, Mestizo, and Black experiences in the Americas.

Mesa-Bains is a stellar storyteller, and the objects and imagery she employs are retrieved from many sources, including personal mementos, historical accounts, ancestral memories, spiritual rendition, folk traditions, domestic spaces, and art history. In her treatment of womanhood, Mesa-Bains presents us with cultural heroes including Dolores Del Rio, Frida Kahlo, and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Her presentation of Frida Kahlo in the late seventies is among the first by an American artist, and she is credited with introducing Frida to a wider audience outside of Mexico.

Mesa-Bains especially admired Dolores Del Rio, the popular Mexican movie star of the 1940s and 1950s. Harriett and I saw the wonderful installations of Mesa-Bains’ Dolores Del Rio at the Mexican Museum in San Francisco [1983] and at the exhibition CARA: Chicano Art Resistance and Affirmation at UCLA’s Wright Gallery [1990]. Mesa-Bains constructed nine installations devoted to Dolores Del Rio. Writing in Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Jonathan Yorba commented: ‘Dolores Del Rio gave Chicanas an alternative to the Anglo-American standard of beauty.”

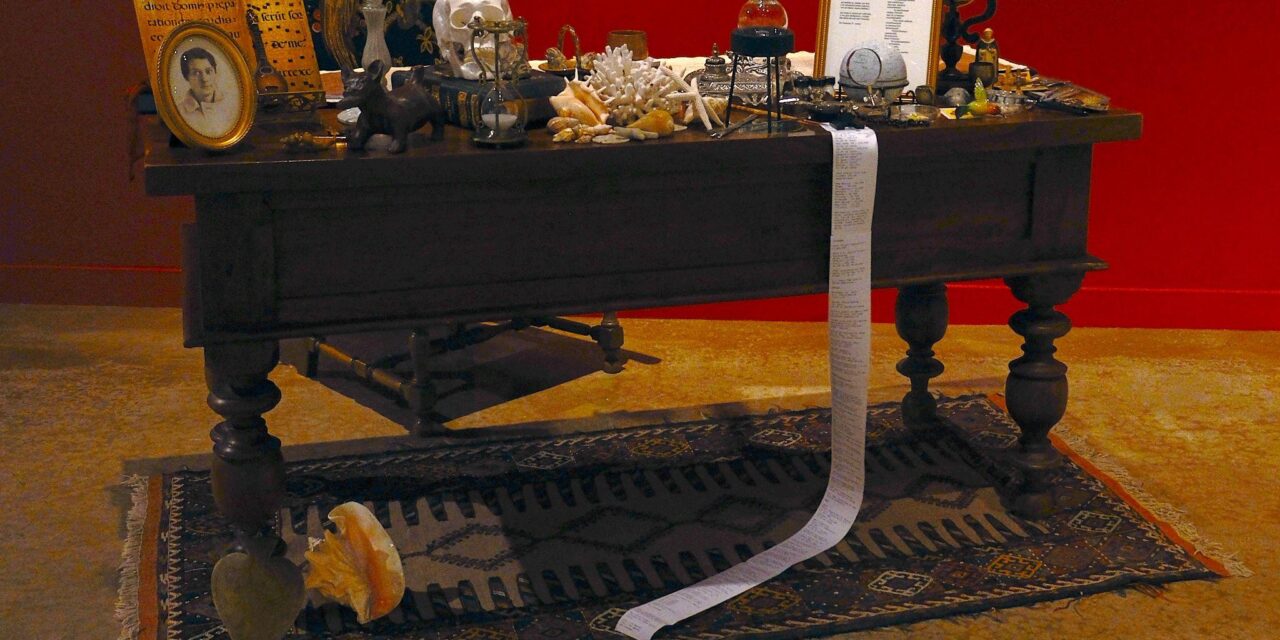

Over the last two decades, Mesa-Bains has broadened her interpretations of an ofrenda and expanded on her installations to include sculpture, furniture, and print collages. In her homage to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, she utilizes a replica of a 17th-century desk with books and objects to illustrate her devotion to scholarship. Sor Juana was born in Mexican City and joined a Catholic religious order as a teen. Scholars note that she began her life as a nun in 1667 so that she could study at will. Sor Juana was self-taught and spent her entire life as a nun assembling a library of over 4,000 books, one of the largest private collections of the colonial period. She became an acclaimed writer of the Spanish-American colonial period writing plays and poetry. Sor Juana is considered the first published feminist in Latin America.

Emma Perez notes “desk-as-altar here figures the predicament, sacrifice, and heroic accomplishment of

brilliant women like Sor Juana under the patriarchal, religious, and social institutions of seventeen century colonial Mexico.” The ‘altar-as-desk’ Perez suggests, “speaks to how cultures are ‘written’ or constructed through the gendering of religious practice and experience.”

The work of Mesa-Bains “is a feast for the eyes” commented SAMA curator Lana Meador. Meador expects the San Antonio community will relate especially to objects and imagery in the exhibit drawn from folk traditions, art history, domestic spaces, spiritual practices, ancestral history, and personal mementos. Mesa-Bains also excavates untold and underrecognized narratives. Her major series of four multimedia installations titled Venus Envy, spans distinct cultures and historical periods to celebrate heroic, archetypal, mythic, and ancestral women.

The exhibit concludes with two powerful mixed-media installations: The Circle of Ancestors and a sculpture of the Rio Grande flowing from the mountains of New Mexico through Texas. The Circle of Ancestors is an arrangement of seven chairs, each chair an altar to a rebellious woman. Among those recognized are her mother and grandmother, Chicana artist Judy Baca, and Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz. Migration across the US-Mexico border has persisted as one of the most pressing issues of our times. Mesa-Bains used hand-blown glass globes to represent the rushing Rio Grande. She placed the names of border towns in Mexico on one side and the United States border towns on the other side of the sculptured rocks.

Visionary Concepts of Amalia Mesa-Bains at San Antonio Museum of Art