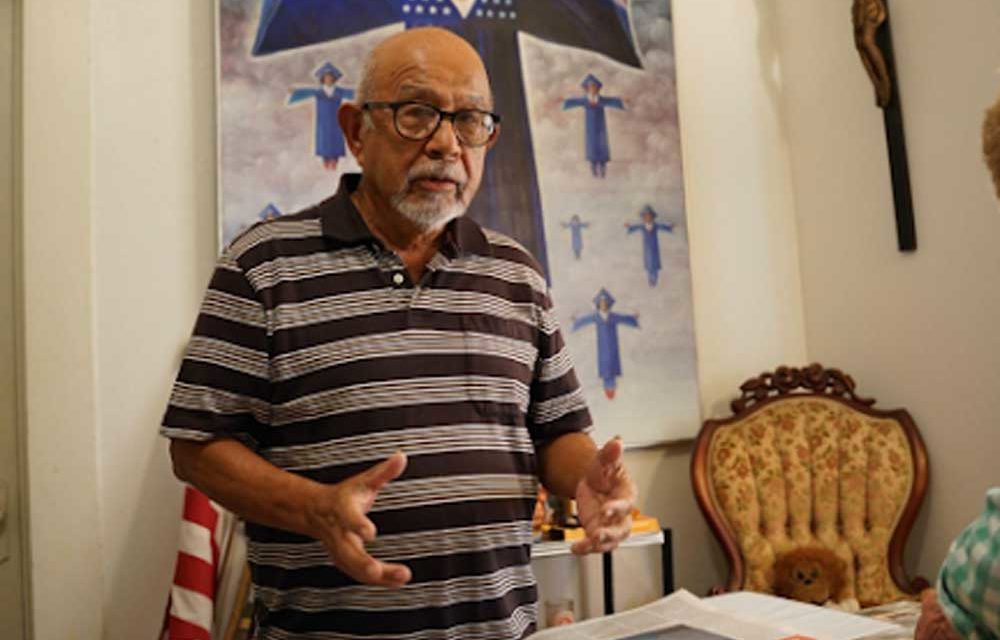

Jose Esquivel, one of the long-time Chicano artists in San Antonio and a co-founder of Con Safo, paints daily, an artistic activity he has committed himself to since the late 1960s. He is one of the founding members of the Chicano art movement in America. Before 1967 when Esquivel began his association with Con Safo, the American art world knew almost nothing about Latino or Mexican American art.

The Con Safo collective of ten San Antonio artists chose to identify themselves as Chicanos. Esquivel documented this art movement, including the preparation of the first Chicano art exhibits in Texas and the Midwest. Smithsonian curators with the Latino Museum recently connected with Jose Esquivel requesting all of his papers for their archives, as well as examples of his art. Esquivel’s artistic journey is an important part of Chicano art history.

One hot summer day in 1947 in San Antonio’s Westside, twelve-year-old Jose Esquivel knocked on the door of Porfirio Salinas, one of Texas’ leading landscape artists who was already a bright star among emerging native Latino artists of Texas. The young boy had been sent by his dad to Salinas’s home to cut the grass and help with other yard chores. Esquivel had never met an artist before, and he was immediately struck by the bluebonnet landscape canvasses piled up in the Salinas’s living room–a studio of a true master of Texas nature painting. Esquivel returned to the Salinas home many times to help with the yard work and other house chores. In the process, he also learned about art by talking to Salinas.

When Esquivel enrolled at San Antonio Technical and Vocational High School three years later, he made the decision to study art. The vocational schools of that era around the country taught only commercial art, but students were also encouraged to learn about fine art. [I know that school program well since I also attended Tech High School]. Esquivel excelled in commercial art, and following his graduation he received a scholarship to study at the Warner Hunter School of Art in San Antonio’s La Villita district. Hunter personally assisted low-income students with scholarships. Esquivel studied with Hunter for five years learning line drawing, watercolor, and oil painting.

Few Latino artists in San Antonio could make a living in fine arts painting, thus Esquivel found work as a commercial artist in the hotel industry. In an era before computers and digital printing, all hotel notices and signs were designed by in-house commercial artists. Signs announcing the location of the dining rooms and conference sessions, for example, were prepared by artists trained in commercial art.

Although Esquivel excelled at this work, he disliked the pressure associated with daily, and in some cases, hourly deadlines, so he left the hotels to work in offices of the city’s public utilities. That job provided better pay and financial security for his family. Esquivel was tasked with making charts and graphs for the company’s board and public presentations. His talents were quickly recognized, and he helped create the first art department of the giant San Antonio utilities company.

A group of local Chicano artists, notably Jesse Almazan, Jesse “Chista” Cantu, and Jose Esquivel, began meeting in 1967 at the Almazan Gallery in La Villita, and the art collective began taking shape. They formally organized when Felipe Reyes joined them the following year. Initially calling themselves Pintores de la Nueva Raza, the members invited San Antonio College art professor Mel Casas to join. Casas proposed that they call their art collective Con Safo. Chicanos in most barrios of the Southwest used the con safo symbol, aka C/S, as a type of king’s x–an understanding or declaration surrounding protection or a shield from personal harm.

In their meetings, the members frequently debated identity issues of being Mexican, Mexican American, or Chicano. They also debated what kind of art represented La Causa, and how best to make their purpose and ideas known. In 1971 Mel Casas, the leader of the group, assigned himself the task of writing a “Brown Paper Report” about the discussions and arguments that the group presented about the meaning and direction of Chicano art.

Esquivel has carefully preserved his notes from the Con Safo meetings as well as documents related to their efforts to exhibit their artwork. At his home, Esquivel showed us dozens of notebooks that documented a full and broad range of debates and discussions about Chicano art. He carefully preserved the flyers, brochures, and photos of their early exhibits, a remarkable documentation of the period 1968-1974. Esquivel’s involvement with Con Safo has now been well documented by Ruben C. Cordova, the author of Con Safo: The Chicano Art Group and the Politics of South Texas. [UCLA: 2009]. This period in Chicano history and the significant role of Con Safo in bringing attention to Chicano art and Chicano artists is not well known to art historians.

Tomas Rivera, a pioneering writer of Chicano literature, assisted the Con Safo art group with an exhibition that he arranged to travel to several cities of the Midwest in 1972. That year, several Con Safo members were also invited to participate in an art exhibit at Trinity University honoring Cesar Chavez. Art historian Jacinto Quirarte met with several Con Safo artists in San Antonio in 1971-72 for his research on Mexican American art. Quirarte, an art professor at UT Austin in the late 1960s and early 1970s, interviewed Casas and several members of Con Safo for his pioneering book, Mexican American Artists [1973].

After Esquivel left the Con Safo group in 1974, he also drifted away from what he called political art. For a time he painted Texana art. His priorities shifted, and he devoted his artistic energies to art that would give him financial stability and enable him to send his children to college. His art sold well, and he was proud to support his son’s education at the Pratt Institue.

The dozens of old photographs in Equivel’s home studio reveal much of his artistic journey. Over the years he met many Chicano artists from across the country. The art in his home, principally of the past 25 years, aptly shows his creativity and exceptional ability to interpret the Chicano experience in America.

Jose Esquivel: Chicano Art Pioneer and Barrio Visual Interpreter