By Dr. William Elizondo

In the ‘60s, it was evident that we were entering an era of great change. If you don’t see people like yourself in leadership positions then you don’t feel a part of that soci- ety. If your children don’t see people who look like them in positions with clout, or people with surnames such as theirs, then they can’t relate to that leadership or see themselves ever getting there. Nowhere was the status quo more entrenched and resistant to change than in the city’s electric utility, City Public Service (now CPS En- ergy). It was city owned, but was actually controlled by an unelected five-man board. The board was supposedly answerable to City Council, but in reality it was account- able to no one but itself. And “itself’’ was also all-Anglo. This arrangement would be a target for reforms by me publicly and by many other fair-minded citizens of San Antonio privately. Since the 1960’s, publically, nobody has attacked the CPS. After I set up my optom- etry practice in San Antonio in 1959, I joined the Junior Chamber of Commerce. I be- came a member of its board of directors. I soon found out that many junior chamber members were CPS employ- ees who had been recruited out of high school, some not even from San Antonio schools. These anointed ones got a college or trade-school education compliments of CPS and had a job waiting when they graduated. None of these fellows were Mexi- can American. I obtained a City Public Service Board flow chart of its leadership in 1967. Of the top 172 em- ployees on that leadership chart, only one had a Mexi- can American surname. For a city whose population was half Mexican American, that was unacceptable. Meanwhile, I knew intel- ligent young Hispanics who had applied for CPS jobs — unsuccessfully. Rohen Alaniz, brother of state Rep. John Alaniz, had a degree in petroleum engineering from Texas A&M, but CPS couldn’t find a position for him. Robert took a job in California and stayed there. A local lad who might have become a CPS executive and a top-flight citizen in his hometown had to take his talents to California to find a successful career. This in mind, I met and spoke with O.W. Sommers, the CPS general manager, 1960 and told him his util- ity wasn’t hiring Mexican Americans for jobs they were qualified to fill. He told me, essentially, there were no Mexican Americans coming out of local high schools who could implement policies within CPS. But, he added, if I would identify qualified Hispanics to him, he’d give them serious consideration for CPS jobs. Of course Sommers’ explanation was nonsense, but I knew two bright women who could challenge his reasoning: Stella Garza and Nora Cabal- lero, who worked in my own optometry practice. In fact, they were my only employ- ees. I urged them to apply at CPS and, lo and behold, they were hired. Either Som- mers was a man of his word, or he was trying to silence my complaining, but Stella worked at CPS till she quit to raise a family and Nora stayed at CPS for nearly 40 years. Apparently she was a good and valuable employee, and her success proved there were solid individuals of Mexican descent who could and should fill good jobs at CPS. It was a good sign, but the Caballero-Garza hires turned out to be exceptions then, not the rule. In 1967, the five-man CPS Board of Trustees – banker Leroy Denman, Joske’s De- partment Store President John H. Morse, businessman Albert Steves Ill, lawyer John R. Locke and San Anto- nio Mayor Walter McAllister – gave us,their customers, an opportunity to make them answerable to us. The board asked City Council for ap- proval to obtain $30 million worth of bonds. I felt that if these bonds were sold it would rubber stamp the board’s policies, including the hiring and promotion practices we’d complained about for several years. I went before the City Council and asked it to DENY the bond request – and allow CPS ratepayers to vote on the bond issue. I also advised City Council that job dis- crimination existed at CPS and CPS should change its hiring policies. Meanwhile, to initiate more credence, LULAC Council No. 2 unanimously passed a resolution. It said, among other things, that the CPS Board in no way rep- resented the average home- owner or gas and electricity consumer in San Antonio; that CPS customers were paying exorbitant and out- of-proportion rates and; that the average local consumer paid more per kilowatt hour than the national average of other public utilities even though San Antonio had the dubious distinction of being classified as a low-wage town. LULAC also resolved that discrimination against Mexican Americans had been freely practiced by the CPS Board for 25 years in both employment and pro- motions. I had appeared before City Council in the past on other issues such as the national vision programs, and I could relate to the council mem- bers. My voice resonated with some of them and others respected me. I’m sure they wanted to appease me, so the council, in a consensus precipitated by the mayor, decided to appoint a com- mittee, which they did, to investigate the alleged job discrimination at CPS. Baugh and his committee went at it hard. I appeared at one of the panel’s first meet- ings and asked the CRC to agree that we had a serious problem at the CPS Board, namely that the board al- lowed the exclusion of Mexi- can Americans in many job categories and that it had the indices of panern discrimina- tion. We identified about a dozen Mexican Americans who said, anonymously. they had applied for a job at CPS and were told, in effect, “We don’t hire Mexicans.” Another two-time CPS Job applicant, Carmen Aguilar, obviously a brave woman, put her testimony in a letter: “I reapplied for a posi- tion and was again told they didn’t hire Mexicans. Of course, then I told the clerk personnel, ‘What happens when a cashier can’t speak Spanish and a customer can’t speak English?’ The reply was, ‘We just collect for utility bills. They have to bring someone who speaks English.’ To this date, I don’t see how our money is any different, yet we cannot get positions because we are Mexicans. I believe in a city like this, especially in city offices, employees should speak both languages. “ Weekly CRC meetings that fall and on into 1968 dis- closed more about the CPS Board’s hiring practices than the utility company probably wanted disclosed. For example, Mexican 23 de Diciembre de 2018 La Prensa Texas SAN ANTONIO 5 Americans held only 2 per- cent of the white-collar jobs at CPS; there were no (zero) Americans of Mexican an- cestry even in mid-level jobs (i.e., electricians, line- men, machinists, carpenters, meter readers, cashiers, as- sistant general bookkeep- ers – some 40 job cat- egories in all); that 80 percent of the Mexican American hires were laborer jobs; that of the 400-500 CPS jobs that came available each year, many were filled by people recruited from outside Bexar County; that in some work classifications, there were no Mexican Americans in jobs that required only a high school diploma; and, to cite one such job category, of 230 work- ers in the electrical dis- tribution department, not a single Mexican American. Mexican Americans were afraid to climb telephone poles, one CPS fore- man explained. In Feb- ruary 1968, the CRC announced there was discrimination in the CPS Board’s hiring and promotion practic- es. Baugh’s committee offered recommenda- tions aimed at rectify- ing that discrimination, among them: The CPS Board should include Mexican Americans trustees in proportion to their share of San Antonio’s population; that CPS should seek out and promote Mexi- can Americans who had been bypassed through the years and; that the CRC should report the progress in achiev- ing the CPSB ‘s goals every 30 days. In a letter to City Coun- cil, CPS Board Chairman Leroy Denman spat on the critics, calling the CRC’s work a “report,” not what it was: actual findings Den- man added: “The facts show that in jobs leading directly to advancement to super- visory positions twice as many Mexican Americans as Anglo Americans were added to the board payroll from 1963 to 1967.” A big fat lie. Denman’s response contended that “this record speaks for itself and clearly demonstrates that unproven charges of discrimination are false.” A few months later, the Federation for the Advance- ment of Mexican American leaders recommended me and engineer George Ozuna as candidates to fill the next vacancy on the CPS Board. Meanwhile, we recommend- ed grocer Eloy Centeno as a third possibility. In the spring of 1969 a vacancy occurred. On May 28, City Councilman Pete Torres, an ally in our battles with the CPS trustees, and I met with Den- man and dis- cussed ques- tions about filling the va- cancy. Den- man refused to meet with a group called the Ad Hoc C o m m i t t e e for La Raza, which want- ed to suggest possible Mex- ican Ameri- can candi- dates for the CPS board.

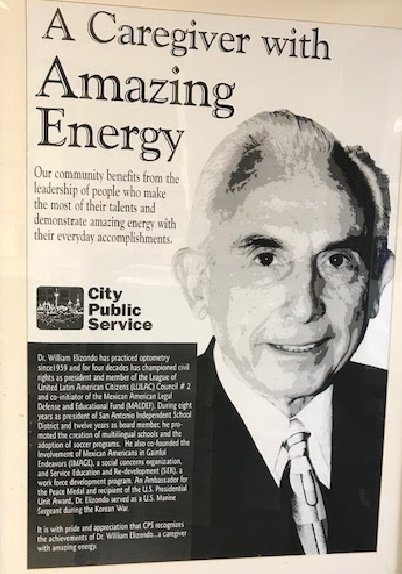

On June 19, 1969, in an arrangement orchestrated by Mayor McAllister, the CPS Board chose Mayor John Gatti to fill vacancy. Tor- res said the seat should have gone to a M e x i c a n A m e r i c a n and called the board’s move “a slap in the face to many people.” The Sunday Sun ran a long story on March 30. 1969, under the headline “Dr. Elizondo serves community,” that praised me for taking on the big boys in the big institutions. The Sun story called me the “instigator of the movement to investigate discrimination with- in the City Public Service Board,”(CPSB) and noted that the Community Relations Commission had found “discrimination existed in the CPSB against Mexican Americans and Negroes,” and; Eloy Centeno was named to the CPS Board on Jan. 31, 1970, replacing Den- man, whose term expired. Centeno was the first Mexi- can American on the CPS Board. It was announced that he would “train” for his place on the board, something Gatti wasn’t required to do. While Eloy’s appointment was good news, it was a long time coming. The board should have better represent- ed the community all along. Putting a Mexican American on that hidebound board was real progress. A Mexican American had finally won a seat in one of the San Antonio’s most exclusive clubs. It made the city a fairer, more inclusive city, one where all citizens could hope for a better job and a better life, a better place to live, work and raise a family. I am proud of what we accomplished. While members of the CPS Board seemed to loathe and fear my intervention into board activities in the late ‘60s, decades later in 2004 at a public event, CPS called me “a caregiver with amazing energy,” noting that “our community benefits from the leadership of people who make the most of their talents and demonstrate amazing energy with their everyday accomplishments.”

This design is wicked! You definitely know how to keep a reader entertained.

Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start

my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Fantastic job. I really loved what you had

to say, and more than that, how you presented it.

Too cool!