In the late 1680’s, New Spain had become alarmed because of French incursions into its northern most undeveloped territory. As such, it organized its forces and sent them to explore and determine to what extent the French had made inroads. In June of 1690, after several attempts to locate the French, Gen. Alonzo de Leon, the younger, discovered the ruins of Fort La Salle in the Matagorda Bay area. As a result, New Spain issued orders to begin the exploration, colonization and Christianization of the Native Americans in their new undeveloped area to become known as the Province of Texas.

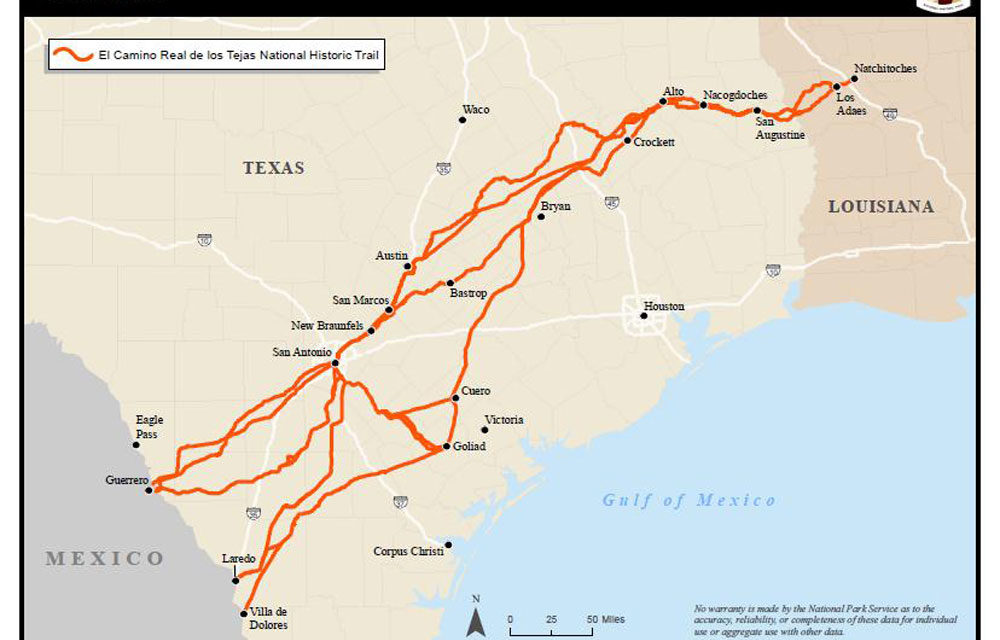

All of the initial and continued expeditions began at the Presidio del Norte and the San Juan Baptista Mission which was fifteen miles below present-day Eagle Pass Texas on the banks of the Rio Grande River. Nearby, there was a natural ford known as “Paso de La Francia”, French Pass. The ford had a solid rock bottom and only about six inches of water running over it. This shallow river condition allowed both men and horses to cross without problems. All of the New Spain forces would begin their treks here and proceed northeast to the Sabine River and other points north.

The commanders of these first expeditions would recruit their troops from the nearby presidios and receive the bulk of their supplies from Monclova and Saltillo Coahuila. All of their men, horses, and quartermaster supplies would arrive at the presidio to begin their departure. The Franciscan Padres would also come for the journey to the new Province of Tejas. Later, the crossing was referred to as the “gateway” to the new province. Years later, Laredo would replace it as the most well-known crossing.

Although initial journeys discovered Indian and animal trails traversing the current counties of Maverick, Zavalla, Frio, Atascosa, and Medina, the first expeditionary forces numbered around seventy-five mounted cavalrymen, a remuda of 500 hundred horses, a mix of two hundred head of cattle and hogs and the remaining quartermaster supplies and other personnel. This resulted in a long military caravan challenged to move in concert through the wilderness to reach its final destination in the east.

Other historians have reported that there were existing animal and Native American trails in the woods that would have made travel easier for the military mission. I submit that these trails would not have accommodated the large and almost unwieldy expeditions that required sufficient space for transportation of the soldiers, animals, and supplies. At best, the native trails would have signaled a way to water and back to the many wilderness areas the natives occupied. Yet, the military would still need to develop strategic maps of travel to its destinations and back along with tactical means to ford rivers, protect against hostile actions and develop roads to provide transportation for its military missions.

The first leg of the expeditions generally crossed the Nueces and Frio Rivers and arrived at the Medina or the San Antonio Riverbanks as a half-way point to presidios and missions in the east. These rivers had good running water and were teeming with fish. The military developed “Parajes”, stopping points to rest, reconnoiter and reassemble its expeditions. Often, flooding of these rivers caused traffic to move further north or south to enable the fording of the rivers. Also, hostile Native American actions contributed to the roads to move further south to avoid combat.

From the Medina “Paraje” the forces would continue northeast and establish “Parajes” at the Guadalupe, Colorado, Brazos, Trinity, Neches, Angelina, and the Sabine Rivers. The original march was to the new Capital of “Los Adaes” in present-day Robine, Louisiana. From these military efforts, some of the trails would be incorporated and improved for travel and other sections of roads would be constructed for suitable transportation. Major stopping points moving east were San Marcos, Austin, Bastrop, and Nacogdoches. Continued military and civilian use improved the Camino Real emanating from the south to the east.

Adding to the increased development of the Camino Reales network, the roads emanating out of the Villa de Bexar, San Antonio, were the roads to Goliad, San Saba, Laredo, and beyond. These roads initially served the presidios and missions in the north and south to the Gulf of Mexico. All of these roads served to provide transportation for troops and supplies to their final destinations.

Ultimately, San Antonio became the hub to supply the far-off presidios and missions. The city still has many remnants of the “Old Camino Reale”, for example, Laredo street still goes to Laredo, Texas, Nacogdoches Street goes to Nacogdoches, Texas. Goliad and San Saba Streets still lead to the old presidios and missions in Goliad and San Saba, Texas.

The Caminos Reales, King’s Highway, was indeed an important part of the original military mission to explore and protect its borders and ultimately served as a transportation network for colonization of the entire province. The first soldier settlers of the Texas frontier who became known as Tejanos were responsible for the construction, maintenance, and use of the Camino Reales. This contribution to the early development of Texas is an important legacy and heritage of the story of the native Tejanos! Also, this road system contributed to the transportation network of the American Southwest. Viva Tejanos!

Caminos Reales/Kings Highways