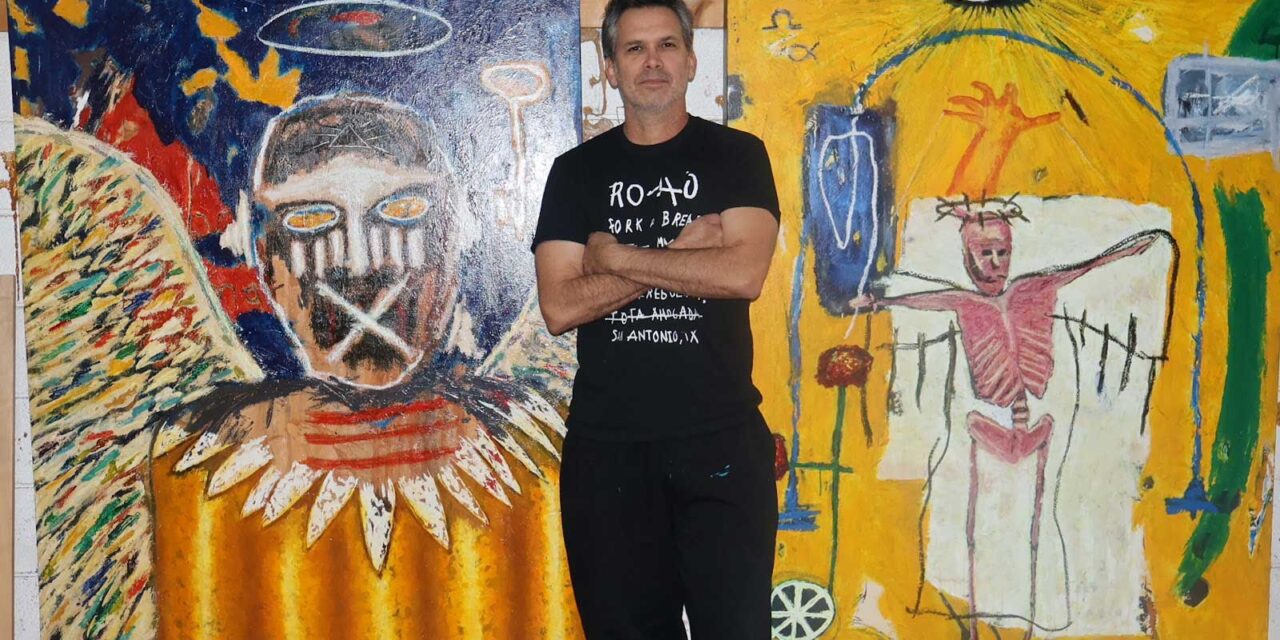

On February 15, 2024, La Universidad Autonoma de Mexico [UNAM] opened Jorge Rojo’s stimulating exhibit “Trece Años en San Antonio,” [Thirteen Years in San Antonio]. The title is a reference point for Rojo who views his 2011 arrival in San Antonio as transformational. His search for a new career led him to study the culinary arts, open a restaurant, and cultivate an untapped passion for painting.

Jorge Rojo grew up in Guadalajara, Jalisco, one of Mexico’s most beautiful and artistic cities. His mother Maria Teresa Orozco was a painter and introduced Jorge to the arts. He recalled that as a young child, his mother called on him to take notice of what she was painting. He credits his mother with teaching him how to observe.

Rojo’s family also encouraged him to visit Jalisco’s museums and learn about the Mexican historical painting tradition. Guadalajara, founded in the mid-1540s, is Mexico’s second-largest city with a metro population of nearly five million. Rojo reminded me that one of Mexico’s most famous painters, José Clemente Orozco, resided in Guadalajara for much of his life and today several of Orozco’s most famous frescoes are located in buildings around the city. [Rojo’s mother has a distant kinship to José Clemente Orozco]. A visit to the Guadalajara would not be complete without seeing Orozco’s famous fresco at the Cabana Hospice, a former 19th-century orphanage now a UNESCO World Heritage site and home to one of Orozco’s most famous murals, “Man of Fire.”

Rojo left Guadalajara in 2001 and opened a restaurant in Leon and Cuernavaca. While he was in law school, he had a well-paying but uninteresting job with the City of Guadalajara serving in the City’s Morgue’s legal department. His daily work with the dead led to a near career burnout and left a mark on his life. He arrived in San Antonio in 2011 to study culinary arts at St. Philip’s College in San Antonio. Upon completing his culinary degree in San Antonio, he enrolled in the Fine Arts program at St. Philip’s to fulfill a long-time desire to explore painting.

After Rojo completed his two Associate Degrees at St. Philip’s, he decided to remain in San Antonio and open a Mexican restaurant. His restaurant, Ro Ho, located north of downtown near the International Airport, specializes in pork and bread similar to that prepared in Rojo’s hometown of Guadalajara.

Rojo wrote, “Running a restaurant in the United States leaves little free time, but the desire to create serves as a guiding force in finding at least some free time.” On one of my visits to Ro Ho, Chef Rojo had just finished baking several trays of freshly cooked “Birote salado” [baguettes]. Emperor Maximilian I introduced the baguettes to Mexico Maximilian I served as Emperor of the Second Mexican Empire from 1864 until his execution by military forces under Benito Juarez in 1867.

In the Ro Ho restaurant, Chef Rojo has two of his paintings, one of Maximilian and the other of Juarez facing each other. The words “Fi Fi’ are painted on the Emperor while “Chairo” is painted on Juarez’s portrait. The phrase Fi Fi is a political reference currently used for the Mexican elites, and Chairo is a name reserved for the humble working class.

Rojo’s paintings at the UNAM exhibit present a historical overview of the period from the pre-Columbian era to the present century. One painting, an Olmec head, adds a new twist to a popular Mexican ancient sculpture. The artist placed flowers in outer spaces around the ancient Pre-Columbian object. Giant stone Olmec sculptures are originally found in the Veracruz jungles. These colossal sculptures made of basel stone range in weight from six to fifty tons. In addition to the artistic incorporation of flowers, Rojo added red-colored lips to the Olmec face in his painting. Many viewers of these original mammoth objects in Veracruz’s museums may have assumed the sculptures were a tribute to a warrior or god, but the red lips in Rojo’s painting make us rethink these assumptions.

The powerful image of the Conquest portraying an Aztec warrior in hand-to-hand combat with a Spanish soldier, merits a thoughtful and comprehensive viewing. In the aftermath of the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521, European artists portrayed the battles with the Aztecs as one of David vs. Goliath with the Spaniards as the underdogs fighting much larger armies. These early paintings always depicted Spaniards winning over the Indigenous forces. In Rojo’s painting, the Aztec warrior appears to be nearly victorious in battle.

Rojo adds humor to many of his works as in the painting of a calavera [skeleton] with a basket of baguettes balanced on his head on his way to make a bread delivery. The delivery boy is aided in his journey by an angel figure riding on his front handlebars while a devil figure rides on the back of the bike. Rojo is a bike enthusiast who has built his bikes and I am certain he has hoped he would ride with an angel when he speeds along in San Antonio traffic.