The National Hispanic Cultural Center [NHCC] is located in Albuquerque near the banks of the Rio Grande and is adjacent to the historic Camino Real. Founded in 2000, the Center is supported by the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs and the National Hispanic Cultural Center Foundation [NHCC]. The NHCC’s mission is “preserving, promoting, and advancing Hispanic culture, arts, and humanities.” Since its founding, the center has been at the forefront of presenting the work of Chicano and Latinx artists.

The National Hispanic Cultural Center founders understood that Latino art in New Mexico had long been neglected, frequently “defined by narrow terms, often stereotyped, and at times overlooked.” Certainly that was the case before 1990. In the 1989 Catalog of a New York exhibition featuring Latin American artists, The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920-1970, only one New Mexican-born artist, Eduardo Chavez, was included. The exhibition listed 140 U.S. and

Mexican artists. However, Chavez was born in New Mexico and grew up in Colorado.

As Hispanic, Chicano, and Latino art exhibits appeared in Los Angeles, San Antonio, and Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, New Mexican Hispano artists took notice. Today, the National Hispanic Cultural Center’s permanent collections in Albuquerque exceed 3,000 works. The Director of NHCC is Zach Quintero, a dynamic leader committed to promoting the arts of New Mexico and the Southwest.

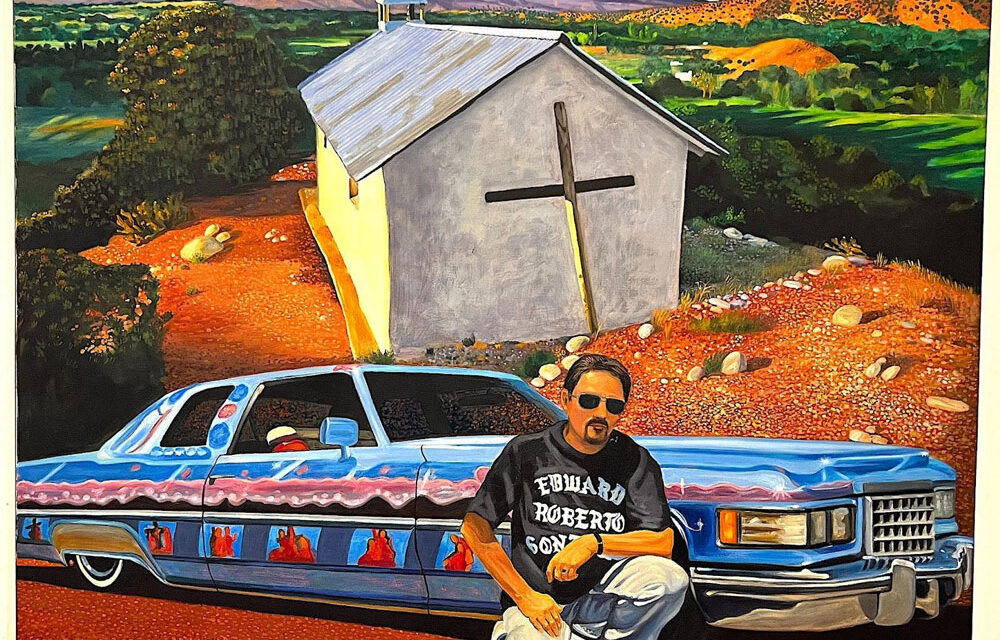

The first exhibit Harriett and I saw upon entering the NHCC museum was ¡Aquí Estamos! New Selections for the Permanent Collection. That exhibit featured mainly New Mexican artists. We were especially captivated by the

work of Edward Gonzales, one of New Mexico’s best-known artists. He is among the few artists to receive an Honorary degree of Doctor of Fine Arts from the University of New Mexico and the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. Gonzalez is a founder of the Organization of Hispanic Artists which succeeded in establishing the Contemporary Hispanic Market in Santa Fe in 1990.

Harriett and I visited the Santa Fe Contemporary Art Market at the end of July and marveled at what has been described as the largest venue for contemporary Hispanic artists in the United States. The Market provides Hispanic and Chicano artists the opportunity to sell art, interact with other Latino artists, and build their resumes.

Gonzalez, a figurative painter, is best known for art based on his own life experiences. His mother’s family came to the United States from Mexico in 1908 and settled in southern New Mexico. His father’s family came to Nuevo México with the founders in 1598. Gonzalez described an interest in creating art “that motivates an appreciation of the culture of the Southwest, expresses the human spirit, and celebrates the beauty of nature.”

The NHCC hosted a new exhibit, “Convergence X Crossroads Street Art,” curated by Rebecca Gomez. The exhibit consists of several museum walls filled with street art, a category not usually viewed inside museums. Gomez notes that street art depicts a “cultural convergence of differing styles” from across New Mexico, Texas, Arizona, and California. She explained that at its core, street art is about “skill and ingenuity, community accessibility, neighborhood reclamation, and peer mentorship and culture.”

The museum gave Shek Vega, a San Antonio native and prolific painter and muralist, a large space to feature two of his mural panels. One mural panel with the words “El Camino” and “Slow Ride” depicts the many attributes of his generation living La Vida Loca [The Crazy Life]. Shek stated that his tios and tias [uncles and aunts] introduced him to what he called the crazy lifestyle, known

by many Latinos as La Vida Loca. One mural panel focuses on the Vatos Locos’ pleasures and vices including hanging out in pool halls, drinking beer, riding the “slow ride” of an El Camino car, and hanging out with women. His mural panel also includes images that portray struggle and violence.

Shek is known for his street art, but his work is seldom seen in museums. He is one of the most prolific muralists in the United States. More than half of the one hundred murals his art companies Los Otros Murals and San Antonio Street Art Initiative created are in San Antonio. The two panels included in the NHCC exhibit are dazzling examples of his superb application of color and space. Shek’s second panel “Neighborhood Watch” is a commentary on the gentrification of his South San Antonio community and the degradation of the Art District in Southtown. He incorporates the words “For Sale” and “Motel” with figurative imagery of greed and deception. Shek suggests that homes were razed so that a motel could be built. The center of the “Neighborhood Watch” panel portrays a naive cartoon mouse adorned with a green bowtie haplessly witnessing the destruction of a Latino community.

Albuquerque artist Nani Chacon’s mural and sketches for the El Paso Museum of Art are featured on a third wall of the “Street Art” exhibit. Chacon, a Navajo and Chicana artist, was born in Gallup, New Mexico, and raised on the Navajo reservation. A large photograph of her mural from the El Paso Museum of Art is centered ten feet above the floor. Below the mural photograph are two preliminary sketches of the murals in the early stages of development.

Chacon’s rendering of a young Navajo woman in a field of flowers with a blue background is stunning. Murals are usually permanent constructions painted on outdoor walls, thus the inclusion of a lifesize photograph of the mural makes the work available to a larger audience.

The largest mural in the “Street Art” exhibit was a collaborative work of Southern California and New Mexico artists. The 3B Collective mural is impressive in scale and imagery. The completion of this mural, which occupies an entire wall of the NHCC Museum, required two creative phases. Three major panels brought from Los Angeles represent the work of 3B Collective artists Adrian Alfaro,

Alfredo Diaz, Aaron Douglas Estrada, Oscar Magallanes, and Gustavo Martinez. The indigenous imagery of faces “smile now, cry later” was painted on the wall with the assistance of Mario Votan Hernandez [Votan-Ik], a New Mexico resident who received his art training in Los Angeles.

An image of a large Olmec head in the 3B Collective mural represents the oldest known indigenous culture of the Americas. Votan refers to the Olmec people as founders of the first nation of the Americas. On the top center of the mural, the artists painted a green nopal [cacti] with red, green, and white ribbons representing Mexican nationalism. An indigenous figure with the words “Dreamers” represents the modern narrative in which Mexican youth in the United States await U.S. citizenship. A Mayan warrior on the left of the mural stands next to a burning Spanish church. The panel offers other imagery that represents Southern California culture.

The NHCC in Albuquerque is reaching out to include Hispanic/Latino/Indigenous artists from across the U.S. Southwest and beyond, exposing viewers to the diversity and depth of Hispanic art and culture. The Center invites Latina/o curators to organize exciting creative and informative exhibits to entice visitors to New Mexico.