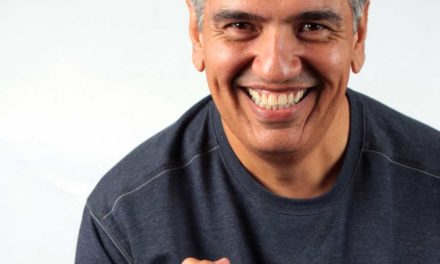

Vincent Valdez had a triumphant return to San Antonio Artpace after an absence of ten years. Now living in Houston and Los Angeles, Valdez presented a new work, “Siete Dias/Seven Days,” his installation at the Artpace “Undercurrent” exhibition, last week to an overflow audience. His previous exhibition, The Strangest Fruit, opened at Artpace in 2014. Over the preceding decade, he has received some of the nation’s highest art awards, including being chosen in the first cohort of the Ford and Mellon Foundation Latinx Artist Fellowships, a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, and residencies in Canada, Vermont, and Berlin.

Vincent Valdez grew up in the Southside of San Antonio, close to two of the city’s historic missions. As a young boy, Valdez admired the artistry of his grandfather and spent his youth drawing and painting. As a young teen, Valdez took up mural painting under the mentorship of another young San Antonio artist, Rubio. Joe Luna, Valdez’s high school art teacher at Burbank High School, whom my wife Harriett and I met recently, described Valdez as one of two “Michaelangelos” he ever met. The term is one of endearment and recognition of extraordinary talent. The other “Michaelangelo” was Jesse Trevino, a classmate Luna knew from Fox Tech High School.

After graduating from Burbank High School, Valdez attended the Rhode Island School of Design where he expanded an appreciation of color and space. After graduating college, some of his early works included three-dimensional wood paintings. His first major oil works on canvas, which he began while in Rhode Island, borrowed from historical themes and incidents as in the case of a painting depicting the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots of Los Angeles. We met Valdez twenty years ago after he completed his studies in Rhode Island and moved back to San Antonio.

We last visited Valdez in the spring of 2017 at his studio in Houston as he completed one of the oil paintings for the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. The New York Times recognized Valdez for his completion of a powerful painting “The City I” depicting a Ku Klux Klan gathering on the outskirts of an unknown metro area.

The KKK series followed earlier paintings he named “The Strangest Fruit” that depicted figures lynched by the Texas Rangers and vigilantes. The “Strangest Fruit” paintings showed young Latino males dressed in regular street clothes, some handcuffed, in a position suggesting they died as a result of being hung by the neck, as were many Latinos and Blacks during the active period of the KKK in the early 20th century in Texas. The title of the series reflects the title of a 1939 song “Strange Fruit” by the famous African American singer Billie Holiday describing the horrible lynching of Blacks in the U.S.

We saw Valdez’s best-known art piece The City I at the Du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac Museum in Paris in 2023. His work accompanied the exhibit “Black Indians de La Nouvelle-Orleans” in a section of the exhibit explaining the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. The heyday of the KKK was in the 1920s, but Valdez’s painting presents a modern version of the dreaded Klan. Valdez’s subjects hold smartphones and stand near a late-model Chevy pickup. The hooded subjects are gathered in contemporary times, a reminder that racism and hate are still evident today.

Writing in the popular art magazine Artnet, Sarah Cascone interviewed Valdez in 2018 when the Blanton Museum of Art at UT Austin acquired the Klan painting. His response to her questions presented a rich understanding of his purpose in painting The City I. He told Cascone: “My work often relates to past events in American history that have been marginalized or silenced or entirely erased.” He described “The City I” as having cinematic features because of the large black-and-white images. Valdez added, “Some viewers may glance at this and assume this is a haunting image of the Klan in 1939 in the American South, but when you look very closely, I lure you in with those details.” The painting completed in 2015 features Klan members holding an infant, canned soda, torches, and banners with an internet tower in the background. He has successfully blurred “that line between past and present.”

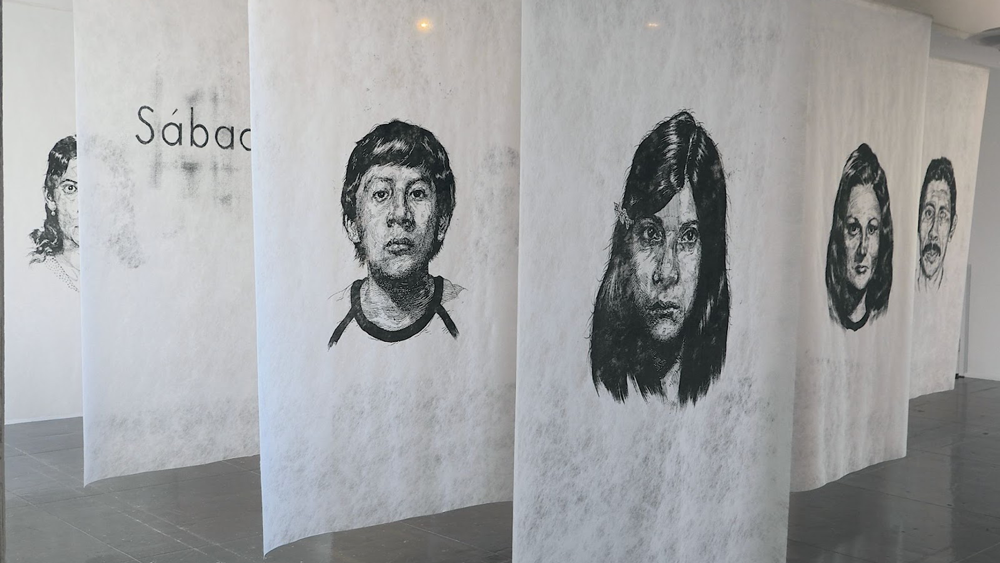

“Siete Dias/Seven Days” is Valdez’s title for his new Artpace installation in the second-floor Hudson Showroom. Guest Curator Zhaira Constiniano of the Art League Houston noted that Valdez’s work “features twenty-one suspended banners depicting haunting portraits of individuals who have disappeared in Central and South America since the 1970s.”

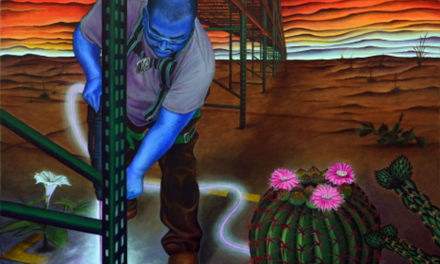

Curator Constiniano offers that Valdez’s figures “are arranged in a chapel-like formation, emphasizing the collective loss and ongoing search for answers surrounding their disappearance.” Seven of the banners have text panels in Spanish representing each day of the week, “serving as a poignant reminder of the passage of time and the enduring absence of these individuals.” On the side panels of the Hudson Showroom space, Valdez displayed works by Luis Jimenez and Rubio, two artists he credits for mentorship and inspiration.

The story of missing persons and “enforced disappearance” is one of Mexico and Latin America’s most tragic realities. In 2023, the International Committee of the Red Cross reported that Mexico’s official number of missing people grew to over 100,000 for the first time. Washington Post journalists researched this alarming tragedy and estimated that since 2006 more than 79,000 people have disappeared in Mexico.

Enforced disappearance is a significant matter in other major countries in Latin America as well. The Latin American Post recently estimated that in the last two decades, at least 200,000 people have disappeared throughout Latin American countries. The vast majority of these disappearance cases go unsolved. In most cases, according to the British Broadcasting Corporation [BBC], the victims end up “unidentified in morgues across the country or buried in clandestine graves.”

Valdez mentioned in his presentation to the Artpace audience at the show’s opening that as a younger artist, he found few art pieces he could identify with in his art history courses until he discovered the work of Chicano artists and the way their work reflected protest, political power structures, and the experiences of Chicano and Latino communities. Valdez graciously recognized the important influences of prominent Chicano artists from San Antonio and Texas who have influenced his work and career.

It is impossible to view the work of Vincent Valdez and remain unmoved by the injustices he presents. The eyes of the disappeared from the portraits of the panels in the installation “Siete Dias/Seven Days” will haunt viewers and hopefully motivate activists and future generations of artists to continue the dialogue.

Latino Artist Vincent Valdez Makes Viewers Aware of Enforced Disappearance