Diana Molina’s 2020 book, Icons & Symbols of the Borderlands, is a rich compilation of more than 100 contemporary art images and photographs of the U.S.-Mexico border. She notes that the artists, all members of the Juntos Art Association, “explore the region’s animal and plant ecosystem, food and religious culture, and history.” The book is based on an exhibit curated by Molina which opened at San Antonio’s Centro de Artes in 2017 and has traveled to five cities over the past five years.

Molina is no stranger to the borderlands. She lives on a mesa overlooking the Mesilla Valley near Anthony, New Mexico, a few miles west of her hometown of El Paso. She grew up in the Texas border town’s famed Segundo Barrio, a few blocks from the Rio Grande. Her early interest in computers and programming led her to the University of Texas at Austin in the late 1970s where she majored in computer science. Following her graduation from UT Austin in 1981, she joined IBM working in the early stages of robotics and automation.

The high tech world bored the young Latina and she left IBM in 1987 to pursue a career in photography and writing. Molina found work in Amsterdam as a photographer and writer for international magazines including Esquire, Elle, National Geographic Traveler, and Vogue.

In the late 1990s Molina moved back to Texas and dug deeper into her Mexican roots. After learning that her great grandmother had been raised among the Tarahumara in the Sierra Madre, she pursued her idea of learning more about this Mexican Indian tribe known for producing some of the world’s best long distance runners. Over the period 1993 to 2011, Molina spent the winters among the Tarahumara tribes of the Sierra Madre. Several of her photographs from that region are included in the book.

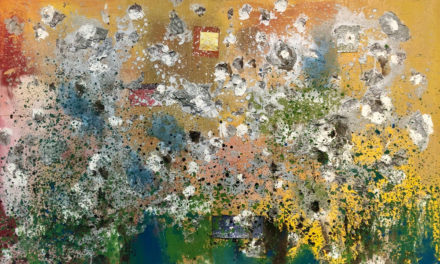

In a Forward for the book, art historian Professor Teresa Eckmann writes that “[w]ith diverse content, style, sources, and materials,” the borderland “artists shape border identity as colorful and dynamic, one full of tension, contrast, and power struggles.” Eckmann, who writes about modern Mexican and Chicano artists, has closely followed the career of several Icon artists, including El Paso native Ricky Armendariz.

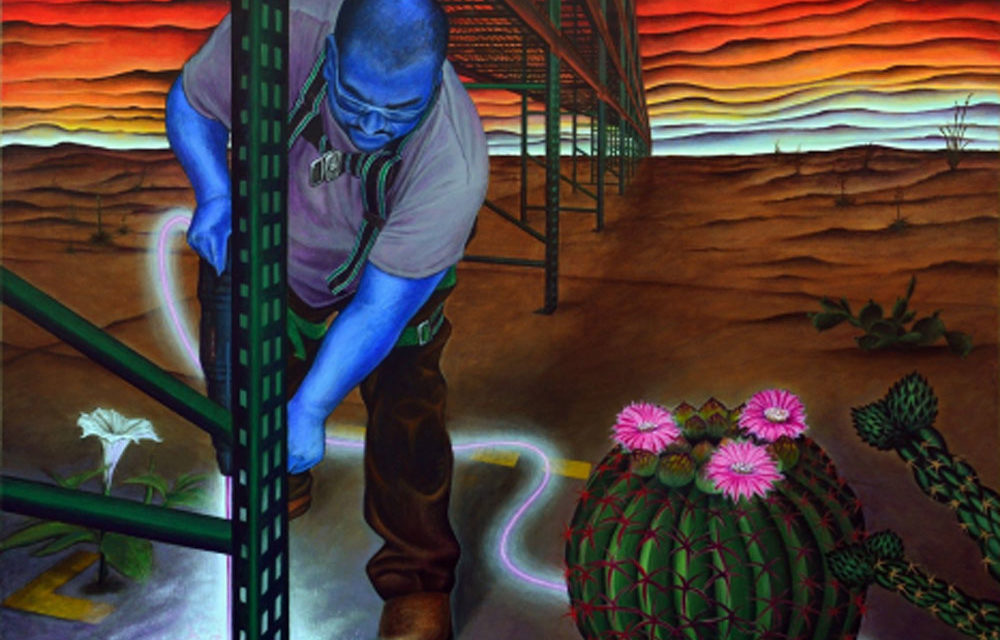

Armendariz uses an electric rotor to carve his drawings onto birch plywood, finalizing his powerful imagery with oil paints. His visual narrative of borderland culture includes wilderness and desert animals, as well as military-like security systems that hunt down immigrants. In one painting of a horse with a machine in his belly, Armendariz explains that he “depicts a horse as a midwife deity ingesting drones and missiles on a dystopian border” [p.54].

Cesar Martinez’s images are recognizable to almost all who follow Chicano art. Martinez was a featured artist in Molina’s curated show at the Centro de Artes in San Antonio in 2017. His digital print, “Hombre que le Gustan las Mujeres” [40 x 32: 2003] is prominently displayed on the cover of Molina ‘s Icon book. Originally painted in the mid 1980s, this popular image has gone through various versions, including a silkscreen print of a similar size produced in the mid 1990s. An oil painting on canvas of a similar image was acquired in 2000 by Chicano artcollector Cheech Marin of California.

Laredo-born Martinez lives in San Antonio and his national reputation was enhanced when he was among a very small number of Tejanos selected for the Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation [CARA] 1990 exhibit in Los Angeles which traveled across the United States. Although his “batos” and “batas” are well known to collectors and museums, Martinez’s art also addresses the borderland environment and the animals common to the region. Martinez captures dust storms, bright suns, as well as jaguars and bulls. Molina’s selection of several of Martinez’s works consciously demonstrates his artistic versatility and brilliant use of color. In 1999 Martinez was the first Chicano artist to have a solo exhibition at the McNay Art Museum of San Antonio, and several of his paintings and prints are currently on exhibit there.

Another portrait in the Icon book is an art piece, “Changing Gears,” by borderland artist Lydia Limas that is based on the difficult lives of women working in the maquiladora industry of the Mexican border towns. In Juarez, Mexico, women work for as little as 55 cents per hour in factories where repetitive work motion competes with daily indignities. Molina notes that “women earn barely enough to support a family and are sometimes subjected to unsafe and unsanitary work conditions.”

I have followed the creative works of many of the artists featured in Icons & Symbols of the Borderlands. I was pleased that Molina included the works of Gaspar Enriquez, an artist I have long admired. Following his career for some 25 years, I have learned much about Chicano and borderland art. Enriquez lives in San Isleta, one of the oldest communities of the United States. His portraits of border people and everyday life in the region reveal the beauty and complexities of the borderlands. His work and that of others in the book should be celebrated.

Molina’s book captures the essence of life along the U.S.-Mexico border and more significantly brings attention to important borderland artists. The Juntos Art Association borderland Icons exhibit opens this May in Carlsbad, New Mexico where it will remain until September, 2021. It is an exhibit well worth seeing.

Diana Molina: The Art of the Borderlands