The myths behind events leading to the Battle of the Alamo are bigger and brighter than Texas itself. Those myths are being challenged in a new book, Forget The Alamo, written by Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlimson, and Jason Stanford. The authors relied on published books and reputable historical studies to make their case that the popular version of events of the battle of the Alamo “owes more to fantasy than reality.”

Conservatives in Texas are upset about this challenge to their cherished myths and as a result new legislation prescribes how Texas teachers can talk about current events and America’s history of racism in the classroom. According to Texas Legislature Online, Governor Greg Abbot signed the controversial legislation HB 3979 in mid June, weeks after the book arrived at bookstores.

The Texas Tribune also noted that the “version signed by the governor also bans the teaching of The New York Times’ 1619 Project, a reporting endeavor that examines U.S. history from the date when enslaved people first arrived on American soil, marking that as the country’s foundational date.” The authors of Forget the Alamo tell a compelling story of the role of slavery in the founding of the Texas Republic, an account that many Texas politicians would rather not acknowledge.

The Burrough, Tomlimson, and Stanford book received a publication sales boost following a cancellation, with only three hours notice, of a historical panel discussion of their publication at the Bullock History Museum in Austin. Right-wing conservative radio talk host Lt. Governor Daniel Patrick took full credit for shutting down the event.

I was born in San Antonio and first learned about the battle of the Alamo as a 7th grade student attending a middle school in an Anglo neighborhood experiencing the first influx of Mexican American students–a total of about 20 of us in a school of 500. I took two buses from my Mexican American neighborhood to get to school.

A film on the battle of the Alamo was shown one day, depicting honest looking farmers seeking to emigrate and being turned away at a border station. The next major

scene of “the Battle of the Alamo” showed the worst of the stereotypical dark characters attacking women and children defended by the valiant Travis and Bowie. There were many chilling scenes, and I turned away for most. Studying for my Ph.D. in history at UCLA years later, I turned my attention to California history and honestly, forgot about the Alamo.

Several years ago, however, I decided to write an essay on Juan N. Seguin, a major Mexican-Tejano figure of that era. With the arrival of my copy of the Forget the Alamo book, I took a special interest in the authors’ discussion of Juan N. Seguin. I searched for insights into how Seguin adjusted to political change and managed different allegiances to Spain, Mexico, the Texas Republic, and the State of Texas.

Juan Seguin was perhaps the most notable, if not the most controversial, of the early Mexican-Tejanos. Seguin, for example, was one of the first Mexicans to befriend Stephen Austin. It appears Seguin saw benefits in Austin’s colonization project. Austin needed a friend like Seguin who was already a political force in San Antonio while still in his twenties. During the Mexican period of Texas, 1821-1836, Juan Seguin served as alderman and as San Antonio’s alcalde, the top office in the city.

In the 1830s Texas had its share of many small

battles, skirmishes, and arrests, including the arrest of Jim

Bowie, a slave trader and grifter. Bowie teamed with LaFitte brothers Pierre and Jean, notorious pirates and slave smugglers, in their efforts to import slaves into Texas from New Orleans in the early 1830s. Slavery was illegal in Mexico. President Vicente Guerrero, Mexico’s first chief executive with Mexican and African heritage, had banned slavery in 1829.

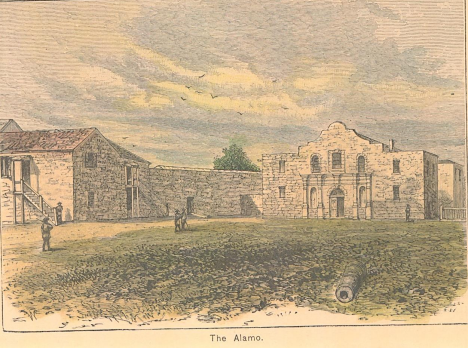

When Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna became president in 1833, he created a Centralist government with almost dictatorial powers. Seguin’s opposition to the centralist Mexican government structure led him to side with the Anglo Texians. He joined William Travis, Jim Bowie, and David Crockett in the Alamo as Santa Anna’s army was arriving in San Antonio. While in the Alamo compound, Seguin was selected as a messenger to covertly seek help from the Texian militia in Gonzales, Texas.

After the fall of the Alamo in 1836, Juan Seguin joined forces with Sam Houston, organizing a Tejano unit to fight in the battle at San Jacinto. Following their victory at San Jacinto, Seguin returned to San Antonio where he won election to the Texas Senate.

Seguin served three terms in the Texas Senate and was instrumental in having all laws printed in both English and Spanish. Seguin stepped down when he was elected mayor of San Antonio in 1841. While mayor, he also chose to fight again in Mexico, assisting the Mexican Federalists in Northern Mexico fighting against the Mexican Centralists’ party. Seguin’s engagement in Mexico’s internal conflicts led to resentment and jealousy among the newly arrived American settlers.

Seguin resigned his post as San Antonio’s mayor in 1842 frustrated with constant confrontations regarding issues of property losses among his fellow Tejanos. That same year Mexican forces attacked San Antonio once again in hopes of undoing the military loss of territory. Although the Mexicans troops were driven back by the Texas forces, Seguin was accused of betraying the Anglo Texians. Fearing for his safety, Seguin fled to Mexico with his family.

Seguin returned to San Antonio after the end of the Mexican War in 1848 and served as a Bexar County constable in the 1850s. Seguin left San Antonio during the Civil War years and settled in Laredo where his son Santiago lived. He died in Laredo in 1890 at the age of 83.

The book Forget The Alamo highlights the role of Mexican-Tejanos like Sequin in Texas history, a history long overlooked. Seguin is one of many Mexican-Tejanos who played significant leadership roles in the founding of Texas. Kudos to the authors of Forget the Alamo for writing an exceptional book that reads well and offers an inclusive and factual account of Texas history.

Latino History Long Neglected in Texas Studies