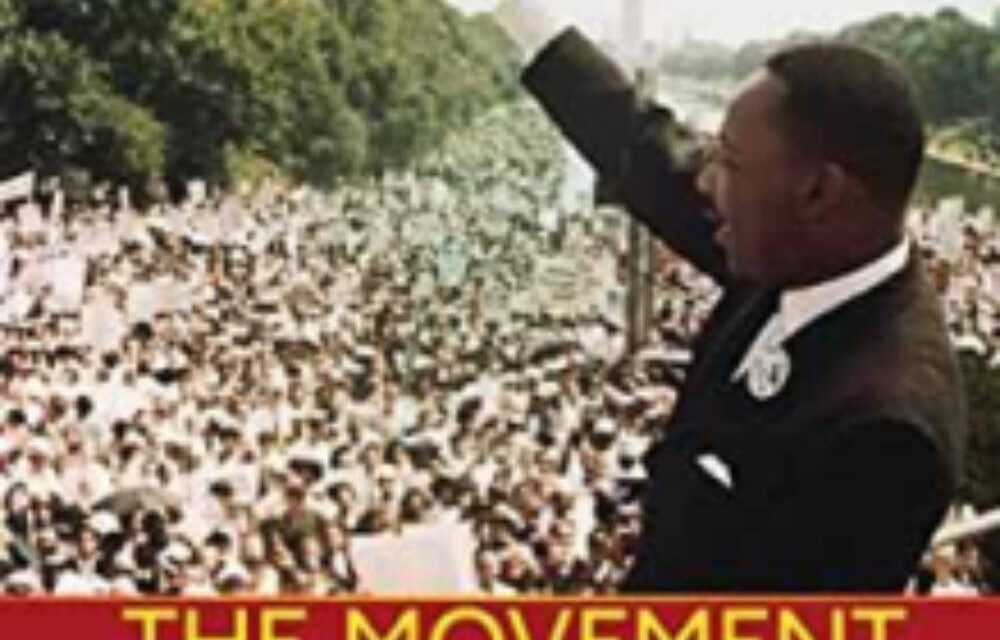

Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke before 250,000 demonstrators for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August of 1963, the largest protest event in American history. He awakened the United States to our constitutional obligations of fairness and justice for all. Sixty years after his speech, his legacy is secure. However, there is less known about Dr. King’s indirect contribution to a rise in Latino awareness of injustices, discrimination, and violence against minorities of color. Here is a part of the Latino historical and legal links to Dr. King’s American dream.

During Dr. King’s generation, Texas and all the Southern States, successfully kept Whites and people of color separated through Jim Crow laws. Jim Crow was a

catch-all term to describe laws and regulations which denied Black children the right to attend the same schools as White children and prevented Blacks from drinking from the same public water foundations reserved for Whites. The laws restricted Black customers from trying on clothes in department stores, sitting at public lunch counters, or drinking from a White restaurant glass. In addition, Jim Crow laws and the racist culture they created, kept Blacks out of most professional jobs and White neighborhoods.

I witnessed the social injustices of segregation as well as the slow transition to greater social inclusion. While some Texas school districts chose to integrate their classes, many schools remained wholly segregated. Some Texas districts desegregated their schools by identifying Latinos as White and busing them to all-Black schools. I attended an integrated high school, Fox Tech in San Antonio,Texas, during the 1960s and prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. I witnessed the segregation policies

that required my Black high school classmates to enter the major theaters in town through a back door located in the adjacent alley. If they rode on the bus, they had to sit in the back seats.

I ran track in high school and on one occasion, after a track meet six of the Fox Tech track team rode together and stopped at the popular San Antonio Pig Stand on Broadway for sodas. The car hop told us that our sprinter, Herple Ellis, who was Black, would have to drink from a paper cup since the restaurant reserved the standard drinking glasses for Whites. One of our Latino track buddies quickly responded, “Bring us all paper cups.” We were caught off guard by the restaurant’s policy since at our high school, which was 99% Latino, Blacks and Latinos all drank from the same water foundation, ate together, and rode the buses together with no distinctions based on race or skin color.

Dr. King fiercely challenged this type of discrimination that. His civil rights activism began with the arrest of Rosa Parks in 1955 for refusing to move to the back of a public bus to allow Whites to sit in the front. Dr. King’s leadership in the Montgomery bus boycott made him a national hero.

Dr. King’s electrifying “I Have a Dream ” speech on August 28, 1963 propelled him to a major leadership position in the civil rights movement. He was instrumental in influencing President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act that banned discrimination in public facilities and private companies such as hotels, movie theaters, and lunch counters. The law also prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

In 1968 a small group of dedicated Mexican American attorneys met in San Antonio for the purpose of launching a Latino civil rights organization. They formed the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund [MALDEF] and selected two San Antonio attorneys Pete Tijerina as director and Mario Obledo as general counsel.

Within months MALDEF had its first case, defending 192 Latino students expelled by Edcouch Elsa High School in Hidalgo County, Texas for boycotting classes with claims of educational neglect and abuse. A South Texas judge agreed that the expulsions violated the students’ constitutional right to protest. It was MALDEF’s first court victory.

In 1973, another San Antonian, Vilma Martinez, was hired as MALDEF’s general counsel and president. Martinez grew up in the eastside of San Antonio, an area with mostly Black and some Latino families. She attended Jefferson High School, The University of Texas at Austin, and Columbia University Law School. Martinez is one of the first Mexican Americans to graduate from the prestigious law school at Columbia. One of her premier tasks as head of MALDEF was helping to secure an extension of the Voting Rights Act to include Mexican Americans among the groups protected.

Martínez also helped obtain a 1974 ruling guaranteeing that non-English-speaking children in public schools could obtain bilingual education. Under Martinez, MALDEF secured an important educational victory– the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1982 ruling in the Plyler v. Doe case that guarantees every child in America a free K-12 public school education, regardless of immigration status.

The civil rights victories of the period 1965-1975 gave Americans of color greater protected rights by ending unconstitutional laws that allowed communities to treat Black and Latinos as second-class citizens. The Chicano Movement protested against poor funding for urban public schools, discrimination against speaking Spanish, unlawful harassment at work places, and unjust deportation of native born Chicano citizens.

Latinos also learned from Dr. King that they would have to remain vigilant in protecting voting rights which once again are vulnerable to political gerrymandering and voter registration restrictions. Although Dr. Martin Luther

King’s “Dream” lives on, the struggles for inclusion, fairness, and justice are far from over.