2024 has been a good year for Latino Art. Museum and gallery shows in Santa Fe and Houston in November and December highlight the deep talent and rich variety of Latino Southwestern artists. First, I call attention to Santa Fe, New Mexico to feature the exciting paintings of Brandon Maldonado.

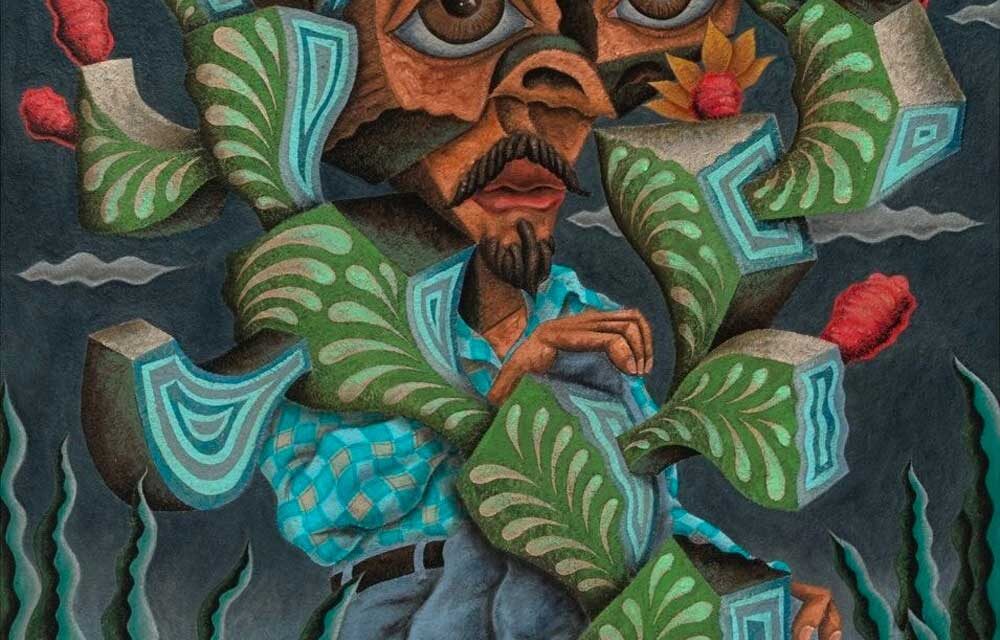

Maldonado’s Hecho A Mano Gallery solo exhibit in Santa Fe opened on November 1, 2024. The paintings presented are a marvelously created Mexican-themed collection of recent works. Maldonado’s creativity is influenced by Mexican artist Guadalupe Posada’s graphic art, the New Mexican retablo tradition, and Pablo Picasso’s abstract cubism. Maldonado noted that he adds a “dash of Picasso-esque cubism sprinkled atop traditional New Mexican retablo folk-art aesthetics like a chef.” His works explore the “ever-present elements from Mexican history and culture.”

The Hecho A Mano exhibit includes a stunning Maldonado Dia de los Muertos piece, “Death of Leroy.” This work memorializes a long-time companion, his dog who passed last year after a long 18-year life. An Indigenous woman holds Leroy’s dead body in a sorrowful pose reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Pieta. The woman’s hair is in a surreal style that mirrors a Mexican Tree of Life candelabra. Harriett and I visited Maldonado’s home studio last year and met the aging Leroy. Last month [October 2024], we visited Hecho a Mano gallery as they prepared for the Maldonado exhibit.

Maldonado grew up in Albuquerque but his ancestral roots are in Northern New Mexico. As a teen, he admired the raw creativity of the graffiti artists who painted his neighborhood’s barrio walls. A self-taught artist, he studied philosophy and religion at the nearby College of Santa Fe. He references these academic influences in his artist statement: “Art merely serves to express an idea; the ideas brought forth by philosophy and religion have always been the realm of the muse for artists, from the earliest cave paintings to the stained glass painted cathedrals.” During the first two decades of his painting career, Maldonado established a regional reputation for Día de Los Muertos-themed images.

Maldonado’s “Still Life” image (at the Border) depicts a border crosser. The migrant tries to camouflage himself behind a nopal [cactus] and remains still, hence the title “Still Life.” However, in reality, Maldonado tells us, the migrant is not an inanimate object. “At his feet are the bones of another migrant who did not survive the journey.” Maldonado’s painting, “Narco Corridos,” is also a work that I am familiar with. It is a painting about cartel violence in Mexico that references the corrido [ballad] songs written about narcos that are popular in cartel culture. A trio of musicians sings a corrido, while a folk saint Santa Muerte [Saint of Death], has a bandolier of cartridges hung across the chest, and holds a victim of drug cartel violence. Two figures in purgatory with chains on their wrists stand below. Maldonado’s Hecho A Mano exhibits closes on December 1, 2024.

In fall 2024, the Art League of Houston awarded San Antonio artist Kathy Vargas a Lifetime Achievement Award in the Visual Arts. The Art League recognized Vargas’s brilliance and her nearly five decades in the arts. Vargas has excelled as an artist, art administrator, mentor, activist, and curator. Her Houston exhibit, Light Needs Shadow Needs Light…, reveals Vargas’s long-time fascination with the themes of life, love, and death. The exhibit challenges viewers to observe Vargas’s four distinct series of meticulously composed, hand-painted, silver gelatin photographs, in which she “weaves together the personal and the political, layering references to fantastical elements from her father’s Mexican folklore and her mother’s devout Catholic beliefs.”

In 2000 Vargas began teaching photography at The University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, and she is recognized for her mastery of the darkroom and photographic process. The Art League commented that in each of her photographs, “the harmonious montage of layered exposures, recurring props, brushstrokes that infuse life into the images, and calculated scratches on the negatives invite viewers to investigate the magic in the in-between.”

Vargas’s professional career as a photographer expands more than fifty years. In 1971, Vargas enrolled in photography classes taught by famed Texas rock and roll photographer Tom Wright at the Southwest School of Art. Over the years 1973-1977, Vargas covered major rock and roll events in San Antonio and South Texas. While constantly on the road, she made time to enroll in art classes at San Antonio College where she met Mel Casas and joined the Con Safo Chicano art organization.

Vargas left Con Safo after a year to spend more time researching Mexican and pre-Columbian myths and literature. Harriett and I met Vargas in the late 1990s when she served as the Visual Arts Program Director for the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio, Texas. By this time she had completed a Lightwork Residency [1995] and an ArtPace Residency [1996]. While at UTSA working in the early 1980s studying with Dr. Jacinto Quirarte, she began working on a documentary project about yard shrines in the barrios of San Antonio and began researching Mexican and pre-Columbian myths and literature. Harriett served on the Board of Directors at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center and knew of Vargas’s outstanding talent. She invited Vargas to be an advisor for an exhibit of San Antonio as a Transnational Community hosted by the Mexican Cultural Center and funded by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation.

In the book Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, author Jonathan Yorba noted that Vargas “draws upon pre-Columbian myths, Mexican Catholicism, Latin American magical realism, and vivid childhood experiences in San Antonio to express the dreams, memories, and nostalgia depicted in her manipulated photographs.” Vargas and Delilah Montoya were among the first Latinas to be included in the Smithsonian Latino art collection.