Going to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art [Met] this month is one of the many ways to celebrate National Hispanic Month. The 150 prints in this superb exhibition Mexican Prints at the Vanguard represent two centuries, from 1750 to 1950, of Mexico’s finest visual and cultural history.

Latinos in the U.S. celebrate National Hispanic Month from September 16 to October 12. We are the only country in the world that joins Mexico in celebrating the end of Spanish rule in the Western Hemisphere colony once known as New Spain. In the United States, Latinos combined Mexican Independence on Diez y Seiz de Septembre [September 16] with Columbus Day and extended National Hispanic Month.

This discussion of Mexican prints is based on a virtual visit to the Met and carefully perusing the museum’s publications, Mexican Prints at the Vanguard [2024] and Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries [1990]. Upcoming art trips to Queretaro, Mexico, and Albuquerque, New Mexico ultimately prevented me and Harriett from seeing the Met show in New York City.

Our introduction to the Met’s Mexican print collection dates back to 1990 when Harriett and I visited the Met to view the extraordinary exhibit Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries. In the Splendors exhibit, the Met included prints by early pioneers of Mexican printmaking: Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, Manuel Manilla, and Jose Guadalupe Posada. Several of those prints are included in the current exhibit. By good fortune, when we visited the Splendors exhibit at the Met thirty-four years ago we found a gallery nearby where we bought several lithographs by Mexican artists in the exhibit.

The prints in the current Met exhibition span two centuries, from around 1750 to roughly 1950. The French artist and author Jean Charlot is credited with introducing Mexican prints to the Met in the late 1920s. A Parisian-educated artist, Charlot moved to Mexico City in 1921, at the beginning of the Mexican mural movement.

In 1922, Charlot joined Diego Rivera to complete the first major mural painting at the Escuela Preparatoria [the National Preparatory School in Mexico City]. Soon Charlot started work on a mural of his own. Art historian Karen Thompson described Charlot’s The Massacre in the Main Temple “as the first work of the twentieth-century Mexican mural movement completed in true fresco.” Nearly all the Mexican prints in the Met Vanguard exhibit were acquired through the efforts and advice of Jean Charlot.

The period from 1870 to 1950 was an extraordinarily productive era for Mexican printers. The Mexican broadsides of the Porfirio Diaz era [1876 to 1910] demonstrated printmakers’ creative efforts to defend freedom of thought and expression. The Diaz dictatorship did not tolerate political opposition, and printmakers employed Calaveras [skeletons] to avoid criticism of personal or political attacks. The prints of two of Mexico’s best political caricature artists, Antonio Venegas Arroyo and Jose Guadalupe Posada, are prominent in the Met exhibit.

Posada was a prolific illustrator creating more than fifteen thousand prints covering topics of criminal activity and natural disasters, ballads (corridos) about popular heroes and bandits, and current events. Posada and his contemporaries were highly talented illustrators and insightful reporters who strove to tell interesting stories rather than dwell too much on why the events were newsworthy. The Met catalog describes Posada’s animated skeletons as “engaged in different activities and frequently deployed for satire and social critique, which have played an important role in establishing the global identity of Mexican art.”

This Met exhibit offers a rich array of prints from the Mexican Revolution era. The Revolution began in 1910 as an uprising in opposition to three decades of authoritarian rule of President Porfirio Díaz and lasted ten years. More than a million Mexican citizens immigrated to the United States during the era. Another million Mexicans are said to have been killed during the years 1910-1920.

In the aftermath of the rebellion, printmakers’ artistic imagery revolved around change, “shaping Mexico’s competing politics, identities, and collective memories.” The Met curators saw great value in the Mexican prints’ narratives in an era when Mexico sought to reestablish its earlier democratic traditions of freedom and justice.

The curators note that following the 1910–1920 revolution, “prints came to serve a broad democratic agenda that sought to educate the Mexican people through art. Art and politics became inseparable.” The Mexican Prints at the Vanguard exhibit brings to light significant prints that “addressed key social and political events in Mexico.”

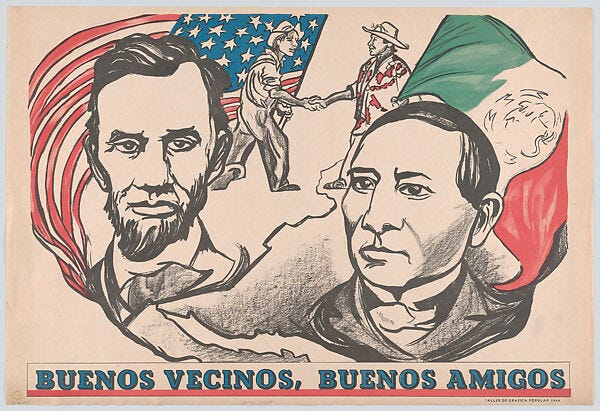

Through the efforts of Jean Charlot, the Met acquired an exquisite collection of Mexican prints from the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP: Workshop of Popular Graphic Art). Under the brilliant guidance of the workshop’s founder Leopoldo Menez, the TGP emerged as the longest-lasting artists’ collective of the twentieth century. First Mendez acquired more than 50 lithographic stones, quality hardwood and linoleum blocks, and a marvelous printing press from Paris, France for the TGP. Next, Mendez recruited Mexico’s top artists, including Diego Rivera, Jose Clement Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Rufino Tayamo, to print with the TGP. According to the Met art experts, the Taller de Gráfica Popular’s “activism and the number of artists involved made it one of the most fascinating groups in the history of printmaking.”

A print example by Taller Grafica Popular founder Leopoldo Mendez. Collection of Harriett and Ricardo Romo.

The Mexican Prints at the Vanguard exhibit reveals that “prints embody Mexico’s political, social, and artistic depth.” The stunning lithographs, woodcut images, and narratives from the post-Mexican Revolutionary period demonstrate that the prints represented a new Mexican political and cultural era. The era embellished modern ideologies of democracy, education, and the avant-garde.

Mexican Prints at the Vanguard captures two vibrant centuries of printmaking in Mexico. Because of Mexico’s rich mural tradition, we know less about the important contribution of the nation’s printers. The Met exhibit indicates that today’s printmaking is inspired by earlier traditions. Chicano printmakers often reference revolutionary heroes, symbols, and themes, and new communities of artists continue to create remarkable posters and flyers for public display and to protest social injustice.