By Dr. Ricardo Romo

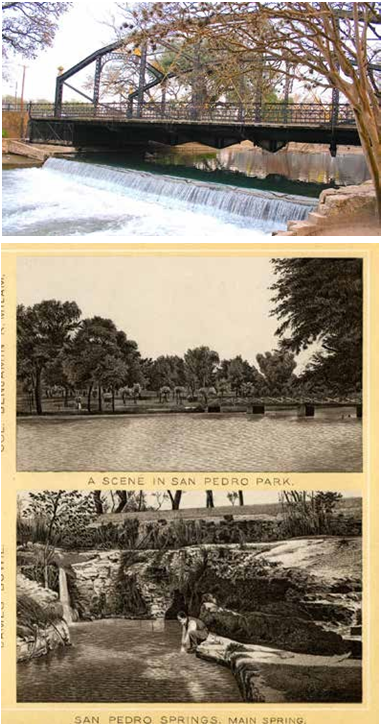

The abundance of fresh water in San Antonio brought the first people to its springs and rivers more than 10,000 years ago. Historian W.W. Newcomb, Jr. writes that “the San Pedro Springs was “the focal point of three or more affiliated Coahuiltecan bands known as the Payayas.” To the Southeast of the Payayas, between the San Antonio and Guadalupe Rivers, were the Aranamas. Authors Sam and Bess Woolford wrote: “Time and the river have stayed on in the green valley. Only the people have come and gone.”

Thus long before Spaniards “discovered” the springs which they called San Pedro and the river they named San Antonio, indigenous people had lived along its banks. The indigenous population of the San Antonio region lived in temporary dwellings which they moved with the seasons. In the 1690s when the Spanish friars and soldiers explored Texas with the purpose of establishing missions and presidios, they identified the presence of fresh water as a major condition for settlement.

Thus long before Spaniards “discovered” the springs which they called San Pedro and the river they named San Antonio, indigenous people had lived along its banks. The indigenous population of the San Antonio region lived in temporary dwellings which they moved with the seasons. In the 1690s when the Spanish friars and soldiers explored Texas with the purpose of establishing missions and presidios, they identified the presence of fresh water as a major condition for settlement.

The Spaniards planned their missions carefully, and they designed the construction of five missions along the San Antonio River to give the mission Indians access to water for irrigation purposes. The acequias (irrigation ditch- es) can be found in numerous sites adjacent to several mis- sions. In Albert Curtis’ book “Fabulous San Antonio” the author writes that “seven acequias or irrigation ditches serviced old-time San Antonio and her four outlying mission farms, and with such success that San Antonio soon became known as ‘the garden spot of Texas’.” Scholars have made note that the first site of the Alamo near San Pedro Springs failed be- cause of persistent floods along the creek. Historians Jesus de la Teja and John Wheat documented one of the first major floods in San Antonio of the nineteen century in an article they wrote in an edited book. They noted: “The disastrous flood of July 1819 strained the community resources beyond capacity. Flood waters swept away fifty-five dwellings, hitting especially hard in the Barrio del Norte.” The flood claimed nineteen lives, most of them women and children.

However, there is a romantic aspect to water as well. The famous Westside high school, Sidney Lanier, is named after the Georgia poet who arrived in San Antonio in 1872 in search of better climate for his consumption. Green Peyton’s “San Antonio: City in the Sun” in- forms us that Lanier “occupied himself by taking long walks beside the river and working on a fifteen-thousand-word sketch of the city.” One might conclude that the river that flowed through San Antonio inspired Lanier.

Until George Washington Brackenridge arrived in San Antonio in the 1850s, no one had ever considered owning the river, more importantly, its headwaters. Brackenridge moved to San Antonio after the end of Civil War and opened a local bank. He also became president of the San Antonio Water Works Company that had a contract to supply the city with drinking water.

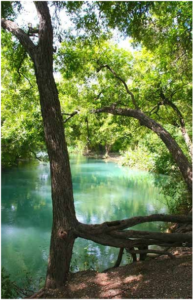

Brackenrige bought the river headwaters and the land surrounding that area of the San Antonio River and by 1883 he held a controlling interest in the Water Works company. He was both generous and vision- ary about San Antonio. His donation of nearly 300 acres of land at the headwaters of the San Antonio River is a great legacy. Brackenridge Park is currently part of that donation. The headwaters, also known as the “Blue Hole” because of its clear blue waters, are located on the campus of Incarnate Word University on land that Brackenridge sold to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word

Brackenrige bought the river headwaters and the land surrounding that area of the San Antonio River and by 1883 he held a controlling interest in the Water Works company. He was both generous and vision- ary about San Antonio. His donation of nearly 300 acres of land at the headwaters of the San Antonio River is a great legacy. Brackenridge Park is currently part of that donation. The headwaters, also known as the “Blue Hole” because of its clear blue waters, are located on the campus of Incarnate Word University on land that Brackenridge sold to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word

One of the most famous San Antonio River stories of the early 20th century concerns the disastrous flood of 1921 which claimed fifty deaths. Much of downtown San Antonio shut down as more than eight feet of water inundated the streets and caused millions of dollars of damage. In the aftermath of the flood, the business community undertook new construction in sixteen blocks of downtown altering the river’s path and cre- ating an island in the center of town. The “island” extends for several city blocks and can only be seen adequately from the air. Plans to alter other sections of the river led to the creation of the San Antonio Conservation Society which pledged to protect the river’s integrity.

The 1921 flood convinced city leaders that the San Antonio River had to be tamed. That year construction of Olmos Dam began as engineers designed 1,941 feet of concrete across the valley between Ol-mos Park and Alamo Heights.

The flooding that had plagued the North Side and Central San Antonio ended with the construction of Olmos Dam in the 1920s. However, other parts of the city were not as fortunate. I grew up in the Westside and the seasonal rains often brought storms and heavy flooding that caused significant damage to property and lives.

Much of the flooding was a result of three major creeks over-running their banks. Mary Beth Rogers’ in her book, “Cold Anger: A Story of Faith and Power Politics” summarizes the disastrous impact of flooding in the Westside. She wrote that during the 1960s when she lived in San Antonio, “someone drowned in a flood almost every time there was a torrential downpour.” The flooding, according to Rogers, affected more than 100,000 West Side families, many losing their lives and homes.

Ernie Cortes, who grew up in San Antonio’s Westside, recalled the many deaths due to flooding as well as the damage to homes and streets associated with the lack of drainage and adequate sewer lines on the Westside. He organized a community based group in the 1970s to address issues resulting from political neglect and discrimination. Cortes enlisted the help of Father Edmundo Rodriguez, a prominent Catholic church leader in the Westside, and the two became the leaders behind the “power politics” that Rogers refers to in the title of her book. They called their organization Communities Organized for Public Service–“COPS.”

Westside parrish members who joined COPS were provided with training by Cortes and Rodriguez. The organizers taught community members how to research city hall records, government documents, and minutes from public meetings. The research paid off when a team of COPS volunteers discovered that the city of San Antonio had approved bonds for drainage improvement in 1945 and Rogers noted: “Not a penny of that money had ever been spent on the West Side!”

Westside parrish members who joined COPS were provided with training by Cortes and Rodriguez. The organizers taught community members how to research city hall records, government documents, and minutes from public meetings. The research paid off when a team of COPS volunteers discovered that the city of San Antonio had approved bonds for drainage improvement in 1945 and Rogers noted: “Not a penny of that money had ever been spent on the West Side!”

Following a presentation by COPS to the mayor and city council, the city agreed upon a $46 million bond issue that would make good on the 1945 agreement. I interviewed Ernie Cortes in the 1980s and he re- called that Westside residents gained political confidence with the success regarding the drain- age issue. For the first time in

the history of San Antonio they felt empowered. Moreover, community members’ efforts to prevent future flooding from the San Antonio River and the Alazan, Apache, and Zarzamora creeks led to the development of a stronger community organization that advocated for improvement in numerous areas to benefit the Westside for years.