Decades ago, we were warned that the insidious contamination of the food web by rampant pesticide could soon rob the world of birdsong. “On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices,” Rachel Carson wrote of this possible future in 1962’s Silent Spring, “there was now no sound.”

The birds are still with us, but the song is much reduced. The number of adult birds has collapsed to the tune of 3 billion birds—that’s one in every four birds—in the span of 50 years.

While Carson’s work helped slow the destruction, the decades that followed have been anything but forgiving. We are in a moment of biodiversity collapse, with our rampant consumption and deforestation debated on international stages along the accelerating climate crisis. Pesticides are still doing damage, as is the loss of habitat to industrial farming and urban sprawl. Cats allowed to roam outdoors in the United States may kill as many as four billion birds per year. And, less discussed, are our lights. Between several hundred million to 1 billion birds die in the US each year due to collisions with buildings and their disorientating lights.

In 2017, building lights lured nearly 400 migrating songbirds, who navigate by the light of the stars, into a skyrise on Galveston Island. The tragedy set in motion a range of responses, including a rapid-response network that today alerts major building managers in Galveston and Houston when large nocturnal bird migrations are approaching.

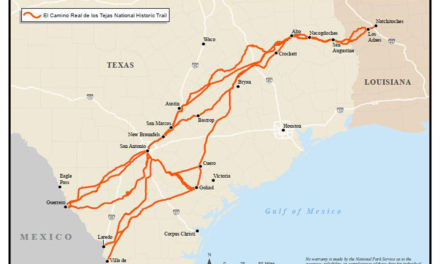

After Galveston renewed interest in their work, scientists at Cornell University ranked Texas cities Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio in 2019 among the Top Ten most treacherous flyways. “Now that we know where and when the largest numbers of migratory birds pass heavily lit areas we can use this to help spur extra conservation efforts in these cities,” one of the researchers said.

In the last two years cities like Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin, and others, responded to this research by passing “Lights Out” pledges. In Dallas, the iconic Reunion Tower dialed back its lighting and the Omni Hotel has been going dark through fall migration.

San Antonio, believed to see far more birds than Dallas, hasn’t made any changes.

A spokesperson for Mayor Ron Nirenberg directed us to a 2020 proclamation recognizing World Migratory Bird Day but didn’t respond to questions about actual policy changes. Prior to unanimously passing the proclamation, Council members commented that the action, which helped facilitate recognition in turn of San Antonio by Texas Parks & Wildlife Department as a “Certified Bird City,” could lead to more dollars from bird tourism at “zero cost.”

The lights have not dimmed. Walking downtown in the early hours this spring and fall, volunteers from Bexar Audubon bagged one-third of likely strike victims in the shadow of a brightly lit Frost Tower.

Last month, the City of San Antonio flipped the switch on their annual holiday River Walk lights display two weeks early, cutting into the end of fall migration. The same night an estimated 60 million birds were flying south across the United States—millions of them through Texas and subsequently, we hope, over the Gulf of Mexico.

A recent investigation by Deceleration shows deeper issues at work in the city. In 2019, City and USDA staff demolished a decades-old rookery at Elmendorf Lake because of concerns expressed by the U.S. Air Force about a potential risk to pilots. But Parks Department staff continued to harass the migratory birds with lasers and pyrotechnics in 2020 even after the birds struggled to rebuild their nests miles further away from the airfield.

“Lights Out” isn’t the first or last word when it comes to what is needed to help birds reestablish their populations. But dimming the lights may be the very least we can do—even if that means delaying the holiday lights until after Thanksgiving.

Mitchell Lake Audubon Center provides an important lesson when it comes to understanding the limits of our ability to repair the damages we’ve unleashed on the birds. Staff there relocated many of likely hundreds of egret nests from Elmendorf to the Southside preserve in the off chance they would be reclaimed by the birds. They were not. They’ve since decayed.

“It was an experiment,” one MLAC staff wrote us, “and it showed that you can’t make birds nest where you want them to nest, even if you give them a head start with a nest.”

Greg Harman is the founder and co-editor of Deceleration.news, a nonprofit online journal responding to our shared ecological, political, and cultural crises.

Texas’s Largest Cities Turning Their Lights Out For The Birds ‘Certified Bird City’ SA Holds Out