The de la Torre Brothers’ art exhibit Upward Mobility at the McNay Art Museum is a breathtaking perspective that combines sensational blown glass, electrifying lenticular montage, stupendously designed wallpaper, the precocious grouping of a lavish dining table, as well as brilliant use of found objects. The focus, according to the artists, is on the “threads of opulence and consumption.”

Einar and Jamex de la Torre apply their thirty years of artistic experience to fabricate this dazzling installation. Raised and educated in Guadalajara, Los Angeles, and San Diego, these brothers are borderland artists who have experienced and witnessed a sense of alienation which they view as a “common predicament in our human condition.”

McMay art curator Rene Barilleaux saw a de la Torre exhibit several years ago and played a major role in bringing Upward Mobility to the San Antonio museum. He described the brothers as “keen observers of the world around them.” Barilleaux noted that their creative approach is additive, “continually combing and expanding meaning using imagery drawn from a range of influences including Aztec mythology, Catholic iconography, German Expressionism, Mexican vernacular arts, and more.”

Harriett and I were fortunate to see a de la Torre gigantic glass tower at The Cheech Museum in Riverside, California last spring. The art column, nearly 25 feet tall, was one of the outstanding artistic pieces in the museum. Two San Antonians, Tomas Ibarra-Frausto and Eduardo Diaz, first introduced the de la Torre brothers to the Chicano art community two decades ago.

The de la Torre brothers divided “Upward Mobility” into four large partitions of McNay’s Stieron Gallery.

The first room is dedicated to the artists’ blown glass sculptures, a craft that Einar [b. 1963] and Jamex [b.1960] first perfected while studying at California State University Long Beach in the early 1980s. The brothers were born in Guadalajara and moved to Los Angeles at a young age. Over the past forty years as artists, they have moved back and forth from their homes and studios in Ensenada, Baja California, and San Diego, California.

In a recent essay, art critic Betti-Sue Hertz commented on the artists’ work which highlights the brothers’ abilities to use their “craft as a means for achieving a levity of humor, a critique of power, and an embrace of symbols and iconography that defies lexicons and canons.” A glass sculpture titled “El Nopalero” and a figure with a lobster head holding a snake titled “The Charmer” intrigues museum visitors. I quickly learned that the exhibit must be seen numerous times because the imagery is vast, complex, and highly ingenious.

To reach the second room, the brothers created a narrow wall passage where both sides are filled with collage wallpaper featuring baroque images. Much like the European artists of the 17th century, the brothers included works for the collage from found objects, mounted deer heads, figurines, and baroque architectural paper images.

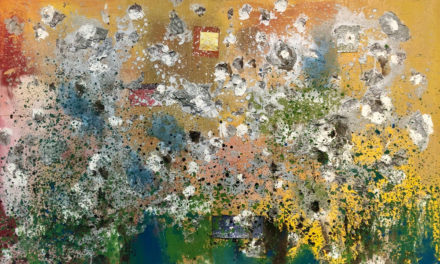

In the second room, which represents the largest part of the exhibit, the artists placed a long banquet table in the middle of the room. The curator described the installation as one reminiscent of a decadent dinner party. The wall description of the installation stated that the artists were disturbed by established aesthetics “being supported by wealth and greed at a time when inequality is reaching frenetic levels.” The artists addressed this theme in their work with an “expression of opulence, angst, and outrage.”

The table is set with elaborate dishware and crystal wine glasses, some spilling over. Several of the elegant chairs surrounding the table are draped with luxurious furs and jackets of the illustrious guests who may have just deserted the table. The celebration appears to have been chaotically interrupted by the mayhem of numerous small animal figures that appear to have taken command of the table.

Several of the works in the second room of Upward Mobility also demonstrate the artists’ baroque theme through the use of vibrant colors, layered textures, and intricate details. Two dynamic elaborate and unusual chandeliers hang over the dining table. The brothers placed a pig figure with a top hat on the table with dollar signs on its belly to support the narrative of society’s reverence of “opulence and consumption.” Several deer heads adorn the walls, and large taxidermied animals walk along the tops of room dividers.

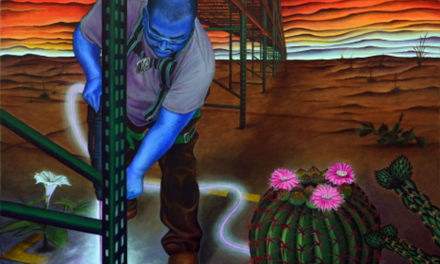

The third room employs two large lenticular prints and a distinct digital visual on the floor supported by an amazing ceiling projection of the Paseo de la Reforma with Mexico City traffic flowing at rapid speed. Visitors to the museum will experience an uneasy sensation walking on the visual as traffic flows endlessly beneath their feet.

On the wall, a lenticular print includes Russian dictator Putin standing on a military tank while over his shoulder is an image of Mexico City’s main cathedral. The Russian leader, with a Frankenstein-like jaw, is shown with intercontinental missiles as the fingers of his hand. A broad highway stretches from the bottom of the painting to Putin’s chest suggesting that violence and destruction seem to lead to the dictator.

In the two main lenticular prints in this room, the brothers continue to follow the baroque tradition in the use of allegory. Their works tell a story and project a message. The art has movement, emotion, and drama in the portrayal of Putin alongside a two-headed Godzilla knocking down the Empire State Building. Images include space aliens, fire, destruction, and chaos– a reminder that Putin, like Godzilla, is set to destroy the civilized world.

The fourth and final room of the exhibit is titled “Colonial Atmospheres“ and visualizes a large Olmec head as a spaceship on the moon. The futuristic story behind this installation is to envision a highly advanced Olmec society that has traveled to the moon. The Olmec head, depicted as a space vessel, features black and white televisions for eyes that follow you around the room and auto hubcaps as landing pads. Worn automobile tires on the floor in various sizes represent moon craters that visitors walk through.

To the left of the Olmec vessel stands the Aztec goddess Coatlicue dressed as an astronaut saluting a weathered flag. The artists explained this scene as one that “reimagines the history of the Mesoamerican people, not as victims of colonization and conquest but as colonizers themselves, taking them to its furthest frontier.”

The images found in the de la Torre brothers’ work are a blend of Mexican, European, and American historical and popular culture that these artists proudly admit to reworking and repurposing. What is new to their recent work is lenticular prints in which the brothers place two central images joined as one. When the viewer moves, one of the images disappears and another image appears when viewed from a slightly different position.

Upward Mobility has many meanings including the brothers’ explanation of a “collision of imagery, themes, and references that are established as our artistic language.” The brothers elaborated, “It is precisely this deep human anxiety and the tenuous balances we keep that we want to express in our works.”