February 2 is the anniversary of the end of the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846 and marks the signing of the peace treaty known as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The Centro Cultural Aztlan commemorates the 176th anniversary of this treaty with an annual exhibition by Texas artists.

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is one of the moast important treaties ever signed by the United States government with a foreign nation. The agreement, also known as the Treaty of Peace, included articles that emphasized U.S. citizenship rights for Mexicans choosing to remain in the annexed areas and stressed friendship and accord.

Under the treaty’s terms, Mexico surrendered 525,000 square miles to the United States, including the land that makes up all or parts of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and the southwest corner of Wyoming.

The treaty had a special provision for Texas which had been annexed by the United States before the war in 1845. Historians agree that the war started in 1845 when U.S. forces crossed into disputed Mexican territory on the Rio Grande River. The Southern States wanted to expand slavery and succeeded with the admission of Texas as a slave state in 1845. Southern politicians sought to extend slavery to California, but that effort failed.

When the Republic of Texas came into the Union in 1845 the U.S. Congress accepted the Texas version of the state boundary extending to the Rio Grande. Mexico never agreed to the annexation and placed Mexico’s northern boundary at the Nueces River, about 100 miles north of the Rio Grande. The U.S. Army entered the disputed territory and Congress passed a declaration of war.

As a result of the Treaty ending the war, Mexico gave up all claims to Texas which the United States had annexed, [illegally according to the Mexican Congress], and recognized the Rio Grande as the U.S. southern boundary. By the Treaty’s terms, Mexico relinquished 55 percent of its territory and received a payment of $15 million, or five cents per acre.

The Treaty was signed at Villa de Guadalupe Hidalgo near Mexico City on February 2, 1848. The Treaty allowed Mexicans living in the conquered territory to be given one year to choose to remain or leave the territory previously belonging to Mexico. If they left, they could retain their property. Mexicans remaining in the U.S. territory were entitled to US citizenship including “free enjoyment of their liberty and property, and secured in the free exercise of their religion without restriction.” Of course, freedom of religion came with U.S. citizenship, but the question of language or the right to speak Spanish was not addressed.

Those Mexicans who remained in U.S. annexed territory became full U.S. citizens. Of the majority of Mexicans living in the conquered area, an estimated 90 percent chose to remain in their respective communities. Some of these communities, such as Santa Fe [1610] and San Antonio [1718] were older than the U.S. Republic.

The Mexican War and the subsequent Treaty of Peace led to renewed political conflicts over the question of slavery and eventually contributed to the American Civil War. The U.S. Congress assured that the new states, principally California, would not join with the slave states.

The Treaty of Peace also clarified issues of disputed boundaries between Mexico and Texas. The United States initiated the war with Mexico over these boundaries to fulfill what it termed the U.S. “Manifest Destiny” to occupy all the Southwest territory extending to the Pacific Ocean. The extension of citizenship for Native Americans and slaves living in the annexed territories was excluded from the Treaty of Peace, but the Treaty made it illegal to purchase “any Mexican, or any foreigner residing in Mexico, who may have been captured by Indians” or to purchase any property stolen by Indians.

In the Treaty of Peace, Native Americans were described as “savage tribes” and were considered combative non-citizens. Immediately after the War of 1846, the U.S. Army established military bases in the newly conquered territory and began a forty-year battle with Native Americans within the conquered territory. The violence directed at Native Americans ended in 1886 with the capture of the great Apache Chief Geronimo. American Indians living in the conquered territory were denied citizenship status until June 2, 1924. In 1948 Native American WWII veterans sued to gain full citizenship. As a result, Arizona and New Mexico granted voting rights to Native Americans.

For nearly 120 years, few Latinos paid much attention to the Treaty. However, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo became a rallying cry for Hispanics in New Mexico in the 1960s. On June 5, 1967, Reies Lopez Tijerina and his La Alianza followers raided the courthouse in Tierra Amarilla demanding a return of Spanish and Mexican land grants they claimed were stolen in the aftermath of the Mexican War of 1846.

When high schools and colleges across the Southwest began offering Mexican American and Chicano Studies classes in the late 1960s, students studied the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. When I taught high school Mexican American history classes in East Los Angeles from 1969-1970, we spent a week reviewing the 1848 Treaty. The celebration of the signing of this peace treaty is known as Segundo de Febrero by Mexican Americans and Chicanos.

San Antonio’s opportunity to recognize and discuss the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo came about with the first Segundo de Febrero exhibit at San Antonio’s Centro Cultural Aztlan in 1977. With the appointment of Ramon Vasquez-Sanchez as Director and Ricardo Jasso as curator, the exhibit became a first in the nation as a thematic art show focused on the Treaty.

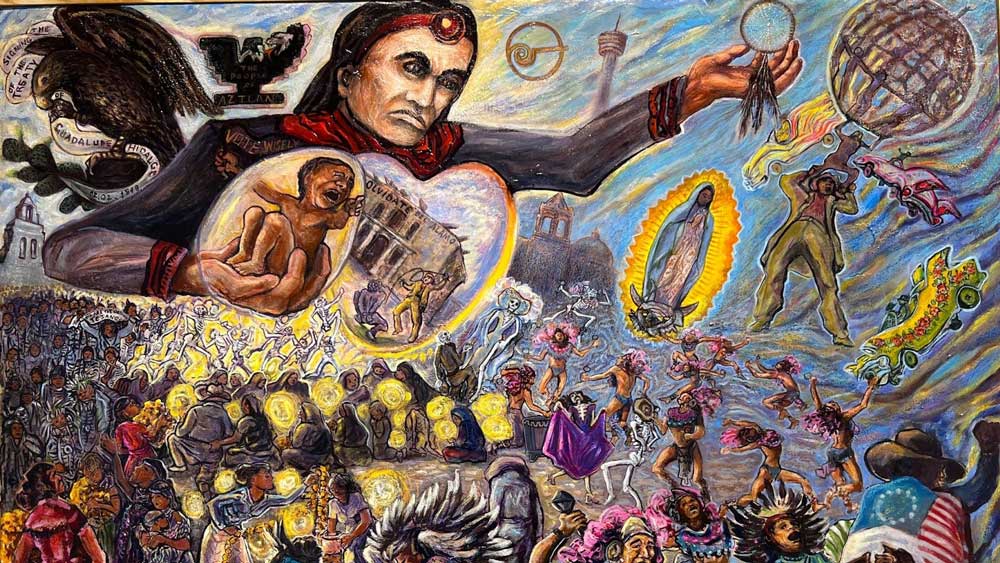

The 47th Segundo de Febrero exhibit at the Centro Cultural Aztlan includes lead artist Mauro Murillo and 15 additional artists. Veteran artist Raul Servin’s painting “The Dream Catcher” is one of the more elaborate and complex pieces in the show. The Servin painting shows a Mexican eagle on the top left corner with a document in its claws noting the signing date of February 2, 1848. In the top center, a Mexican figure holds a child, perhaps a reference to the birth of the Mexican American. Also in the center is an image of a slaveholder whipping a chained slave. Behind the slave owner is a building with the sign “Olvidate del Alamo,” [Forget the Alamo].

One of the newcomers to the Segundo de Febrero annual exhibit is Ricardo Zamora from McAllen, Texas. Zamora creates thematic wire sculptures. For the Centro exhibition, Zamora placed the religious figures Joseph and Mary helping Baby Jesus climb the border wall. The U.S.-Mexican War divided communities and families who lived along the border. We are reminded by Zamora’s sculpture that immigration is an important political issue in the 2024 presidential election. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo gave the U.S. Congress and the U.S. President sole authority to govern the border with Mexico. Governor Gregg Abbott appears to have never read the important articles in this Treaty.

The Segundo de Febrero Exhibition: Seguimos commemorates the 176th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The Centro Cultural Aztlan is located at 1800 Fredericksburg Road, Suite 103. The Opening Reception is scheduled for Friday, February 2, from 6-9 pm. The exhibit is free and open to the public until February 29, 2024. For information call the Centro at 210-432-1896.