An exhibit at the Witte Museum in San Antonio pays tribute to Fernando Ramos, a remarkably talented Latino artist and dance performer from the period 1930 to 1970.

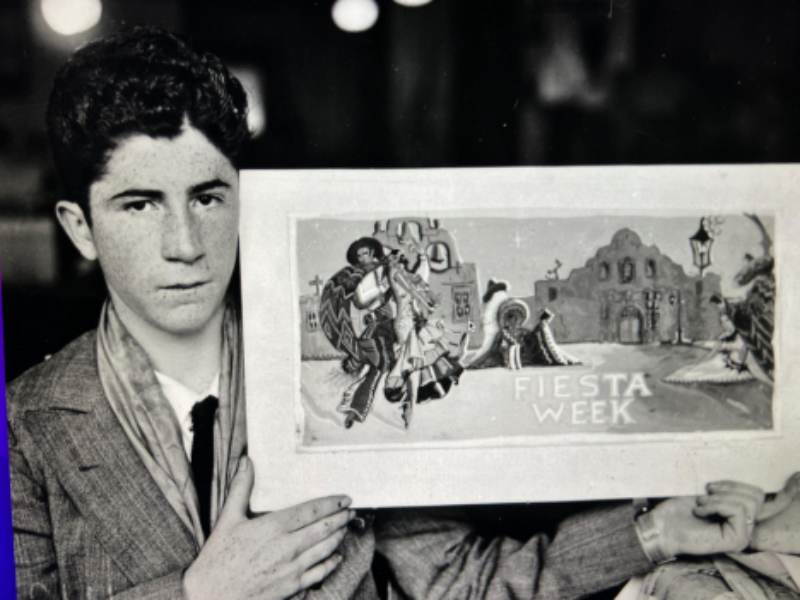

As a fourteen-year-old teen, Fernando Ramos won his first art prize, a citywide poster competition for San Antonio Fiesta in 1929. When Ethel Harris opened her Mexican

Arts & Crafts [MAC] company in 1931, she hired Ramos as her principal designer to add his colorful images of Latino culture to the tiles and other pottery works the company produced. The young teen found time to work part-time at the MAC during his last two years of high school, but he also made time for playing the piano and dancing. In his senior year at Jefferson High School, Ramos won top honors in a statewide high school art competition. Prior to Susan Toomey Frost’s book, Colors on Clay, most Latino art lovers knew little about the brilliant art work of Ramos or his contributions to the work known as San Jose Mission Tile.

Frost documented Ramos’s early years with the MAC and the long-lasting influence his art had on the popular Mexican tile works of San Antonio. Frost noted that as a high school student, Ramos won a national poster award to promote Armistice Day sponsored by the American Legion. By the time of his high school graduation, the young Latino had garnered top awards in city, state, and national competitions, perhaps the first Latino in the U.S. to achieve such artistic honors.

At MAC, Ramos designed scenes of Mexican life, San Antonio traditions and culture, and flamenco dancers for clay pottery, tile table tops, and wall ornaments. His designs dominated the artwork of the pottery company, and Ramos’s contribution was a major reason that MAC pottery and decorative tiles were selected for two different years [1933 and 1934] of the Chicago World Fair. When the Texas Centennial Fair open in Dallas in 1936, the organizers permanently installed a wall of tile made by MAC and designed by Ramos at the Hall of State.

Fernando Ramos and his family emigrated to San Antonio in the mid-1910s just as the Mexican Revolution reached its most violent phase. San Antonio was a haven for Mexican immigrants in the first quarter of the twentieth century as the city absorbed a large share of the one million migrants, or ten percent of Mexico’s population, who fled north to the United States. In 1920, San Antonio had the largest Mexican population in the U.S. with 41,469 Mexican residents. Los Angeles followed with 29,757 Mexican residents.

Not much was known about Ramos’s family or where Fernando Ramos lived when the Frost book was published in 2009. My own research drawn from 1930 U.S. Census data shows that the family resided at 1134

South St. Mary’s Street, just north of downtown San Antonio, a small Mexican colonia not far from downtown Laredito. This would explain why Fernando attended Hawthrone Middle School which would have been close to his home. The 1930 Census notes that Meliton and Refugia Ramos had five children. Fernando was second-to-the youngest. Fernando’s father, Meliton Ramos, is listed as a manufacturer of tortilla machines. Fernando’s older brother, Ricardo, age 18, is listed as working in a tortilla factory. Fernando’s sister, Dolores, worked in manufacturing juvenile clothing, while anothersister worked in a retail store.

Few Mexicans had emigrated to San Antonio before 1910. Immigration had been made easier with the construction of railways leading to the Texas border towns of Laredo and Eagle Pass. Mexico’s growing connectedness to the U.S. contributed to the vast movement–in both directions–of people and agricultural and manufactured products. The Ramos family witnessed the ethnic and demographic transformation of San Antonio. The Mexican barrios of midtown, Southtown, and the Westside began to expand dramatically with the arrival of new immigrants from Mexico. With the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 push factors encouraging migration ushered in a new era for Mexican communities in Texas.

Fernando Ramos led an exciting and interesting life. As a young teen, he studied with the Spanish-Mexican expatriate Xavier Gonzalez, a nephew of Jose Arpa. Arpa, a Spaniard who lived briefly in Mexico, arrived in San Antonio in 1898, and over a thirty-year period had a thriving career as an artist and art teacher. Xavier Gonzalez, also a Spaniard, received art training at the famed San Carlos Academy in Mexico City and at the Art Institute of Chicago. After completing his studies in 1925, Xavier Gonzalez moved to San Antonio where he taught

at his uncle’s art school and also at the Witte Museum. In middle school, Ramos took art classes from Gonzalez, likely in the period 1928-1931. Gonzalez left San Antonio in 1931 to teach in New Orleans.

Gonzalez mentored Ramos well, and when Ethel Harris founded the Mexican Arts and Crafts company in 1931, she found Ramos and quickly offered him a job. She marketed the art created at the MAC at the San Jose Mission Granary compound–a 250-year-old structure with walls two feet thick. The pottery and tile marketed by the MAC was manufactured elsewhere and sold to tourists

visiting San Jose Mission. In the mid-1930s, MAC pottery and tile also became popular with wealthy families in San Antonio. Elite families decorated their homes with San Jose Mission Tile mainly in their kitchens and on outdoor tables.

As an artist, Ramos demonstrated great talent, but the young teen had a passion for dancing, especially Spanish Flamenco dances. In 1934, he walked away from his full-time tile job at the MAC to study dancing in Mexico City. In Mexico City, he met Carla Montel, a native of San Antonio, who made the perfect dance partner and eventually became his wife.

After three years of training, the Fernando and Carla Ramos team toured the U.S. and Mexico with a dance company. In a Mexican newspaper article from the mid-1930s found by Frost, Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas complimented the Ramos dance team “as the greatest interpreters of Mexican and Spanish folk dancing that he had ever seen.” The Ramos dance team also appeared in four movies, including “The Bells of Capistrano” [1942] with Gene Autrey and “The Loves of Carmen” [1948] starring Rita Hayworth.

During the time Ramos was away dancing, Harris copyrighted a catalog of Ramos’s designs with the Library of Congress. Frost noted that the catalog showed Ramos’ drawings of “tortilla sellers and chili queens at Alamo Plaza, colorful carts of flowers and fruit, and a candy seller reading the newspaper La Prensa while waiting for customers.”

Ramos had a remarkably long association with Harris which began in 1931 and continued into the late 1960s. In

their nearly forty-year working relationship, Ramos would return often to San Antonio to make new drawings. Frost told me that on one occasion Ramos was behind in completing an important drawing for a commission, and Harris flew to New York to locate him. Harris managed to corner Ramos backstage at a dance performance and got the drawings she needed. The next day she flew back to San Antonio.

Over a forty-year period of production and sales, the San Jose Mission Tile company utilized hundreds of Ramos’ drawings to produce thousands of tiles and numerous pieces of pottery. The company operated from the early 1930s until its closure in 1977. When Frost published her book in 2009, she did not know when Fernando Ramos died. She later discovered and shared with me a notice from the Los Angeles Times stating that Ramos had passed away in 1969 at age 56. Sadly, there were only two lines devoted to his radiant life in that notice.

Ramos was one of the earliest Latino artists recognized in exhibits and shows of his era. As a performer, he had a brilliant career and was immortalized in several major Hollywood films. While his art can be found in several museums in San Antonio and in various homes and buildings, there is still much to learn about his life and journey to stardom.

Fernando Ramos: The Brilliant Career of an Artist and Dancer