Joe Lopez is known for his portrayal of everyday life in the barrios of San Antonio. His oil paintings displayed at a new Spring exhibition at the Centro Cultural Aztlan are about Mexican American life in a poor Southwestern city where the street vendors pitched their goods in Spanish and accepted only cash. A painting of a vendor with a small cart selling ice cream and frozen paletas and a teen street musician waiting for a song request reminds us that everyone worked, and adult work was often tedious and hard.

Lopez draws upon his memory of days as a teen when ice blocks were delivered to his home and those of his neighbors to keep their foods fresh. Everyone on his block had ice boxes rather than refrigerators. Refrigerators and telephones were viewed as luxury items that few could afford. Growing up, Lopez’s family did not have a phone, but their gracious neighbor lent their phone to them and several other families in the surrounding residential area.

I grew up in a similar barrio, miles from the Lopez family, but in the same city. Perhaps for that reason, Lopez’s paintings strongly resonated with me. I met Joe Lopez nearly 25 years ago, and over the years we have talked often about our barrio life experiences. We both agreed that although we were poor, we did not think much of it or dwell on it.

Lopez grew up in one of the smallest and most isolated Mexican barrios in San Antonio. The barrio earned its name when the Lopez clan were visiting with friends from another barrio. When Lopez described his neighborhood, someone said– “Oh yeah, it is a hidden barrio–El Barrio Escondido.” The Lopez Barrio was next to the famous enclave Cementville where Mexican workers employed by the giant cement factory lived with their families. That Cementville neighborhood disappeared in the 1970s when the plant closed and developers turned the plant into the Quarry Shopping Center.

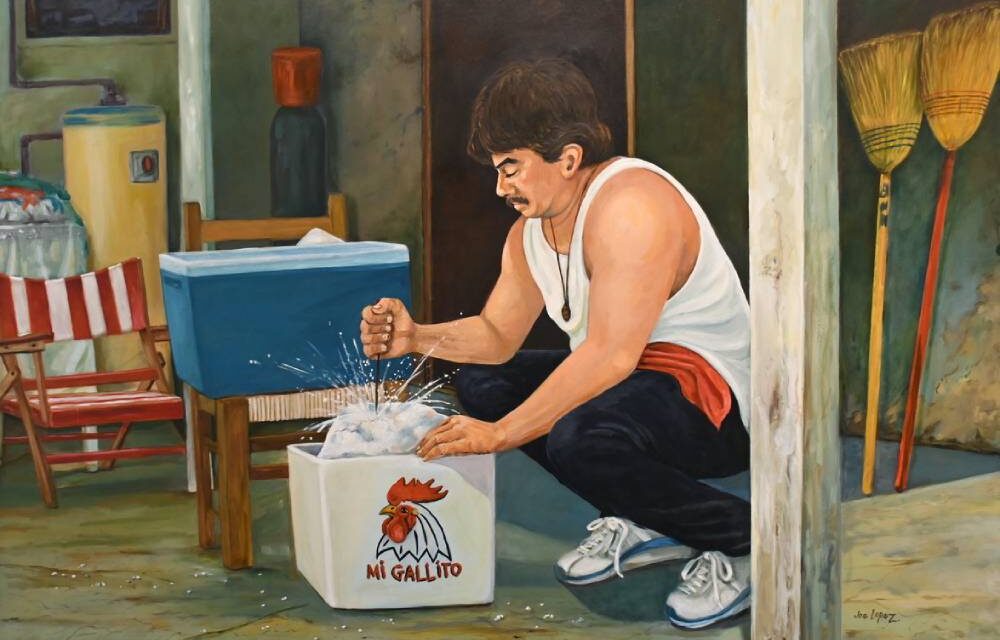

Lopez remembers Barrio Escondido as only one full block. In the 1940s and 1950s when he was growing up there, his community had a rural feel to it. Residents grew corn and vegetables on their properties, and some families in the neighborhood raised chickens and roosters. Lopez

was especially fond of roosters, or Gallos as they are called in Spanish. For the Spring exhibition at Centro Cultural Aztlan, Lopez included numerous paintings that draw upon his memories of life in an earlier era.

Lopez was born with only one hand and a lot of determination and grit. As a young boy he developed an interest in drawing and painting, artistic activities that he enjoyed and that gave him confidence. His teachers took notice of his creative talents and encouraged him. In the 8th grade he earned recognition in a city-wide art contest. One of his teachers, a Catholic nun, convinced the art teacher at the Witte Museum to take Lopez as a scholarship student, noting that Lopez would be willing to clean the studios after other students left. His teacher at the Witte had a full-time job teaching art at Alamo Heights High School where Lopez eventually attended after several summer classes at the Witte. After high school graduation, Lopez also took art classes at La Villita School of Art and San Antonio School of Art through the Texas Rehabilitation Commission.

Over the next two decades Lopez’s occupations earned him a living but did not involve art and proved less than satisfactory. He worked as a gardener, and later found work stocking goods and wares in a small department store specializing in household products.

Then he landed a job in the advertising department at a Dillards department store where he began using his creative skills. Although he enjoyed his work there, he left to handle grocery advertising design for the Centeno Supermarket, one the Westside’s top-selling grocery stores.

Lopez worked in the grocery store for nearly twelve years, finally leaving for a better paying job in a small

advertising agency. During his brief time at the agency he learned to use a computer, a key skill that prepared him for his last major job as a graphic computer specialist with Fort Sam Houston Army Base. After 21 years, Lopez retired from his government job and turned to making art on a full time basis.

In the late 1990s, Joe Lopez and his wife Frances opened Gallista Gallery and art studios on South Flores Street in Southtown. At the gallery they hosted art events and invited artists to exhibit their work. Lopez met nearly all of the major Latino artists in San Antonio and South Texas and credits them with educating him about new art trends while introducing him to Chicano poetry and performance art.

The entrance way to Gallista Gallery exhibited paintings and folk art crafts by local artists. Over nearly two decades, Gallista Gallery hosted monthly art exhibitions, including altars during the Day of the Dead celebrations. Lopez maintained his own painting studio at the Gallery and rented exhibition and studio space to many Latino artists. Although Lopez’s style and techniques evolved during this time, he continued to paint mostly about his Mexican American culture and heritage.

Work is a major theme of Lopez’s new exhibition. A large painting of a bricklayer dominates the center of the show at the Centro Cultural Aztlan. Lopez paints the Latino bricklayer high on a scaffold to demonstrate that work was not only hard, but also perilous. Lifting bricks up to the scaffold was not an easy task, and everyone knew that such work was more suited for younger workers. Many construction workers from the Westside retired before their 50s and took up less strenuous work. Perhaps the man Lopez painted selling watermelons on the side of the highway once engaged in harder work as a younger man.

In the daily lives of the Lopez family, work held a premier value for those young and old, male and female. In some instances, the family created goods through their labor, as in the painting of “Nopalitos,” where women are gathered around a table cleaning nopales grown in their backyard. The nopales might be added to a family meal or

sold at a corner street stand. To Lopez, this represented an example of work as well as a moment when family members helped one another. Two other paintings of agricultural workers picking spring crops capture an earlier era when Latinos who could not find work in the city accepted farm work in nearby cotton, strawberry, or lettuce fields.

Lopez mentioned to me that in Barrio Escondido everyone worked. His mother took in laundry and numerous neighbors worked cleaning houses in the nearby affluent neighborhoods of Alamo Heights and Olmos Park. The painting of a woman seated by herself cleaning nopales or the image of a cook preparing cabrito [a young goat] at a restaurant are but examples of his many observations and memories related to the working class. A painting of a woman waiting for the bus suggests that she is Joe Lopez has returned to his family homestead, but he has added a studio and gallery to the front of the house. Lopez’s preliminary sketches and Gallista Gallery bulletins and notices are archived by the prestigious Smithsonian Archives of American Art in Washington, DC, which is also collecting his memorabilia. Today Lopez continues to paint beautiful cultural works and sells postcards and tee shirts with his Gallista brand images. As for future plans, he revealed: “It is great to be in the barrio where I grew up, and I’m happy to be painting full time.”

Images of the Chicano Barrio: Artist Joe Lopez at Centro Cultural Aztlan