October 12th is recognized in many US states as Indigenous People’s Day, which is celebrated on the second Monday of October. Indigenous People’s Day traces its origins to a United Nations conference in Geneva in 1977 where attendees promoted the principles of “Indegenous sovereignty and self-determination.” Thirty years later, the United Nations gave formal recognition in its United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was adopted in September 2007.

Many scholars also trace its American origins to 1991 when Berkeley, California activists first celebrated an Indigenous People Day. History.Com. notes that as of 2020, “the holiday is observed by the states of Minnesota, Alaska, Maine, Louisiana, Oregon, New Mexico, Nevada and Vermont, as well as South Dakota, which celebrates Native Americans’ Day.”

There is a growing Indigenous population in all of the Americas, most notably in Central America, Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru. In the United States, according to the 2010 Census Bureau, Native Americans numbered 5.2 million people. Today there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States which includes American Indian and Alaska Native, either alone or in combination with one or more other races.

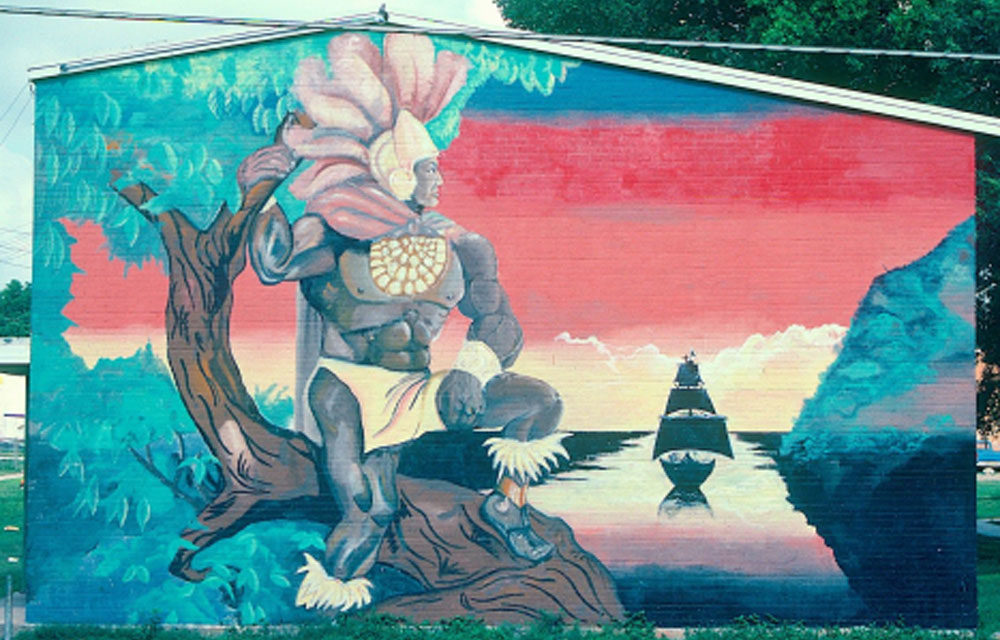

Among the first Europeans to engage the North America Indigenous population were shipwrecked Spanish sailors who arrived by sea landing in Texas with Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca in 1528. They had been shipwrecked near Florida and had crashed their make-shift raft on the beaches of the Gulf of Mexico near present-day Galveston. De Vaca was initially separated from his fellow seaman and was immediately captured by the Karankawas, a coastal Indian tribe of that region.

After six years of living with the Karankawas, de Vaca slipped away in the middle of the night and luckily came upon friendly Avavares Indians nearby. With the help of the Avavares Indians, De Vaca met up with two other companions, including Estevan, an African slave who had originally traveled with de Vaca when they sailed from Cuba to the Gulf of Mexico. They were assisted by the Avavares until they crossed the Rio Grande and pressed forward in their journey walking more than a thousand miles west, then south to find Spanish settlements in the interior of Mexico.

The estimates for the number of Indigenous People in Texas in pre-European years vary, from a low of 50,000 to a high of one million. Most Texas historians believe that it was surely in the hundreds of thousands and documented their presence in every part of the state. Anthropologists have identified 218 Indian bands or “nations” in South Texas. There were at least 55 different bands that spoke the Coahuiltecan language.

The Spanish Crown waited more nearly 160 years after De Vaca’s travels into Texas before deciding to colonize its northern provinces. Don Domingo Teran de los Rios, the first governor of the Spanish province of Texas, traveled to Indigeneous Tejas in 1691 and left us rich details of the land and people in his diary. The native people, he noted, called themselves Peyaye [Payayas] Indians and lived in what he called “rancherias.” There were hundreds of rancherias in this region. Among them lived the Coahuiltecan Indians who lived in a vast area extending from present-day Central Texas to the northern Mexican state of Coahuila.

European settlement of Texas began soon after when Mestizos and Indians from Coahuila in Northern Mexico arrived to build the missions in East Texas and later San Antonio. These early settlers included Indians workmen who were related by language and similar DNA to Indians living in San Antonio.

The Texas Indian rancherias or communities disappeared by the middle of the 19th century as new settlers from North America claimed vast sections of land. While Indians resisted both Mexican and Anglo intrusions into their lands, they were ill equipped to fight with bow and arrows when western Europeans came with large guns, rifles, and cannons.

Today it is common to find families in southside communities surrounding the missions whose ancestors played an important role in the construction of the missions and chapels of that era. Many can trace their heritage to the first Americans and they are proud of their Indigenous roots and Mestizo culture.

As Indigenous People across America strive to improve their welfare and health, while also preserving their culture, they come into daily reminders of past injustices. A New York Times story on October 13, 2020 noted that President Theodore Roosevelt had been quoted as saying that “it would be better if almost all Native Americans were dead.”

Into the 20th Century many history books sided with Roosevelt’s racism and legitimized the actions of Anglo pioneers and settlers who destroyed the homes of Native Americans in the Western territories as the Federal government policies took their land and resettled the Native Americans in reservations. Indigenous Day celebrates a past when Native Americans were free from colonization and warfare.

Indigenous People And Latino Mestizo Culture