Mexico and the U.S. borderlands have produced many artists; however, the number of photographers who have covered both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border is relatively small. Historically, the field is also relatively new. The rise of borderland photography dates back to 1910 with the broad visual documentation of the Mexican Revolution.

Prior to the advent of the Mexican Revolution, there is little record of Mexican documentary photography. President Porfirio Diaz ruled Mexico with a strong and harsh hand over the period 1876–1911, and photographs showing Mexico’s poor people and the country’s economic backwardness, political ineptness, and economic corruption would never see the light of day. Reflecting on these expectations, scholar Rita Pomade wrote: “As those were the Porfirio Díaz years, the demand was for ‘happy’ pictures. Anything else wasn’t good business for the newspapers. 85% of the public was illiterate, and the public that could read – businessmen, large landowners, and the emerging middle class – didn’t want their sleep disturbed.”

Culturally, President Diaz demonstrated an insatiable taste for European music, art, and businesses. Diaz showed a strong preference for the behavior of Europe’s elite upper-class societies with their customs, style, and artistic expression. While Diaz was determined to turn Mexico into a modern country with Mexico City as the “Paris of the Americas,” the vast majority of Mexicans lived in extreme poverty. The few Mexicans who dared tocriticize Diaz’s policies communicated their displeasure in labor demonstrations and through clandestine small press publications.

In an essay on photography, Carlos Monsivais, the great literary author, explained that the absence of photography in Mexico in the 19th century was a consequence of “priorities and patronage: the nineteenth-century middle class relied on pictures only to eternalize the majority–presumed real–of their exterior, physical features.” Photography, he added, was “not and could not be considered an art since they [phtographers] lacked the power to transform the sitters’ greatness and humanity into universally valid objects.”

With the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, photography in Mexico came of age. Many of the U.S. newspapers covering the turmoil sent correspondents and photographers to Mexico. Mexico also had several outstanding photographers, notably, Agustin Victor Casasola. According to Rita Pomade, Casasola and his team “photographed armies attacking railroad trains, rough-hewed soldiers replacing the upper class in what was once forbidden territory in the better parts of the conquered capital, soldaderas giving comfort and food and fighting alongside their men, and the wasted bodies of the dead strewn haphazardly along the countryside.”

Casasola and his brother Miguel formed the Asociacion de Fotogafos de Prensa [Mexican Association of Press Phtographers], an association of 483 photographers. These photographers covered the Mexican Revolution over its ten-year history. They “photographed groups of armed children, the cold faces of executioners, the last moments of those being executed, and the hardened indifference of the living who had seen too much. They photographed with a clear impartial eye the men doing battle on both sides of the fight.”

[Rita Pomade]

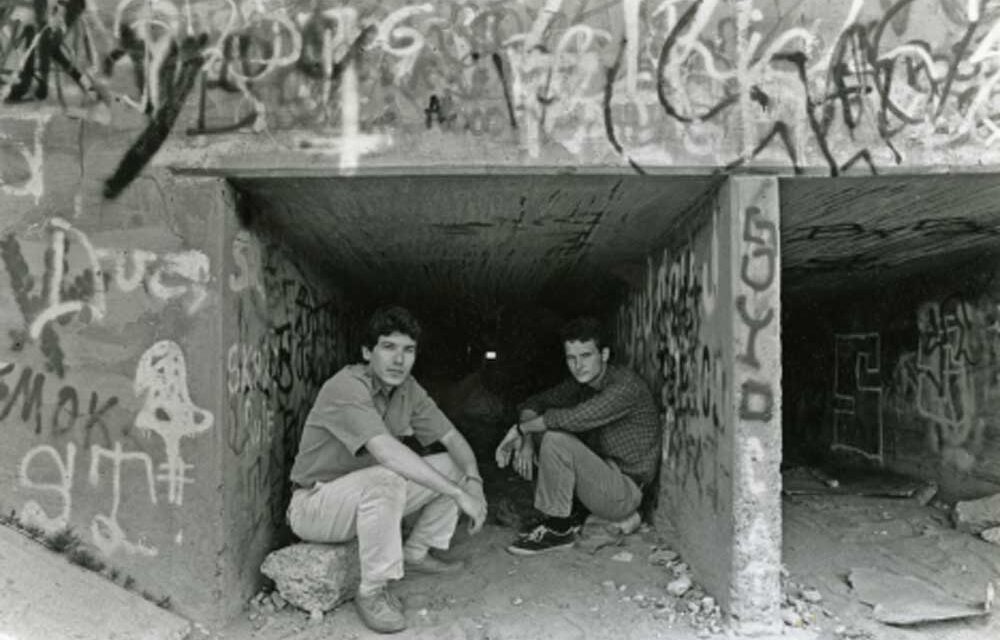

The historical legacies and cultural influences of that monumental revolt can be found in Joel Salcido’s DNA. Salcido, a borderland journalist and photographer from San Antonio, identifies himself interchangeably and with ease as a Mexicano and a Mexicano Americano. Born in Juarez, Mexico, and raised in El Paso, Texas, Salcido has photographed much of the Rio Grande region, including its mountains, towns, and people. His photos cover an extensive area extending along the 830 miles from Brownsville/Matamoros to Juarez/El Paso. A frequent contributor to Texas Monthly and Texas Highways, Salcido is one of the few seasoned Latino photo-journalist commentators of life on the Texas-Mexico Borderlands. A 1908 photo of Salcido’s grandparents shown here is unusual, if not rare, because few Mexican photographers documented la gente del pueblo.

Salcido’s career began with multiple layers of assignments as a photo-journalist with the El Paso Times [1979-1991]. Over his twelve years with the Times, he traveled throughout much of Mexico. He won praise for his documentation of the Tarahumara Indians of Mexico and his coverage of the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City.

Over many years working on the border, Salcido developed an in-depth knowledge of the region’s history, politics, economy, and cultural traditions. In addition, Salcido’s understanding of Latino experiences grew from his assignments for USA Today during the 1980s which took him to most countries of Latin America. As a freelance writer, he is best known for his book on the making of tequila.

In his book, Aliento a Tequila [Spirit of Tequila], Salcido traces the origin of agave plant drinks to the Aztecs. The Aztecs drank pulque which is a fermented product, but not a distilled drink. Once the Spaniards saw that agave juices had potential alcoholic properties then the idea morphed into tequila which obviously requires blue agave and most importantly, distillation which the Spaniards brought via the Moors.

When the Spanish arrived in the 1500s they referred to the agave product as a vino [wine], which of course, was a miscategorization. The Indians of the Jalisco region introduced the Spanish conquerors to the juices from the core or pina of what is known today as the Weber blue agave plant. In Jalisco, there are two regions of growth for blue agave. The highlands are known for their red soil while the lowlands commonly have dark volcanic soil. Indeed the state of Jalisco is famous for its dominance of Mexico’s most famous tequila, 80 percent of which is sold to thirsty American consumers.

Salcido traveled across Jalisco visiting distilleries and artisanal tequileras. He followed the planting and harvesting of agave as well as the culture and traditions of producing the final product. Salcido photographed the entire agave preparation including the mashing of the core or pina of the plant as well as the cooking and fermentation process that turns sugary juices into alcohol.

Salcido continues to photograph the borderlands and is working on an intimate view of the border for Texas Highways Magazine. In addition, he visualizes a long-term project that seeks to find the origins of a popular Texas icon.

Joel Salcido: A Texas Photographer of the Borderlands