The exhibit, Traitor, Survivor, Icon: Legacy of La Malinche, an extraordinary selection of art, opened on October 14, 2022 at the San Antonio Museum of Art [SAMA]. The seventy works of art represent a rare combination of art, history, identity, mythology, and caste. The exhibit succeeds profoundly in its purpose–to examine the story of Malinche, an Indian woman linked to the fall of the Aztec Empire and to the eventual conquest of Mexico. Malinche embodies a broad range of evolving identity and change in our understanding of the political, social, and cultural movements of the past 500 years.

The Legacy of La Malinche explores the way in which Malinche’s story has been told and interpreted over the past five centuries and includes paintings, sculpture, photography, drawings, textiles, mixed media works, and installation pieces. The curators divided the show into five thematic sections: The Interpreter; The Indigenous Woman; The Mother of a Mixed Race; The Traitor; and Chicana/Contemporary Reclamations.

In February of 1519, Hernán Cortés sailed from Santiago de Cuba to Havana and then on to Cozumel, an island on the southern portion of the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico. The distance from Cuba’s Cape San Antonio to the island of Cozumel was less than 50 miles. Cortés sailed with eleven ships, 530 men, 16 horses, and several packs of dogs.

Cortés also brought with him a Maya from Yucatan named Melchor who had been taken to Cuba by an earlier Spanish expedition that had landed in Yucatan the previous year. Initially, Melchor would serve as an interpreter for Cortés. Soon after landing at Cozumel, Cortés’s good luck improved when a canoe arrived carrying Geronimo Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, two Spaniards who had been shipwrecked on the islands years earlier. Aguilar was an ordained priest anxious to be rescued; Guerrero had no such intentions. Fully tattooed, Guerrero identified as a native Mayan and rejected leaving his Indigenous family and three children–the first Mexican-born Mestizos. All of this occurred before Cortés met Malinali–known to us as Marina or La Malinche.

There are many myths surrounding the life of Malinali. One of the myths is addressed in the section of the exhibit, “La Madre del Mestizaje/The Mother of a Mixed Race.” Officially, Malinche’s union with Cortés gave us MartinCortés, the most famous of the offspring between Spaniards and Indian women. But the title of first Mestizos belongs to the three children of Gonzalo Guererro of Yucatan, mestizos who were born some five years before Cortés landed in Mexico.

In the first battle with his Mayan adversities, Cortés’ interpreter Melchor disappeared in the confusion of battle and was later found to have aided the Maya natives. In the next battle with the Chontal Maya, Cortés brought out horses–which so frightened his Indian adversaries that they lay down their weapons. As a symbol of their loss, the Mayan Chief gave Cortés 20 young women slaves. Among the 20 slaves was the young Nahua girl, Malinali.

Cortés certainly had good fortune. The highly intelligent Malinali spoke Nahuatl and Maya. She proved the ideal “Indigenous Woman” having learned Nahuatl as a child and later Mayan while in captivity with the Chontal Maya. Cortés arranged for the 20 women to be baptized, and Malinali became Marina. With the assistance of the newly rescued friar, Geromino Aguilar, who spoke Maya, Marina learned Spanish and became an invaluable interpreter for Cortés as he marched to Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire.

In his letter to the Spanish King, Cortés mentions Marina’s value as “mi lengua,” my tongue. After the conquest of Mexico, the friars, working with Indian artists, produced several codices that placed Marina next to Cortés in almost every important event. The SAMA exhibit includes copies of various documents portraying the conquest of the Aztec Empire.

Marina’s importance is documented in Lienzo de Tlaxcala–when the powerful Tlaxcala nation, enemies of the Aztecs, aligned with the Spanish. Marina is shown translating the conversation between Cortés and the Tlaxcalan leader [43]. The Florentine Codex reported that “a woman, one of us people here, came accompanying them as interpreter.” The Spanish came to Mexico with 530 men, but with the alliances of the Tlaxcala Indians, their army grew by the thousands.

No one knows exactly when Marina became characterized as a traitor to her Indian community, and to an extent, a traitor to Mexico. Nor do we know for sure when and how she came to be called La Malinche. She was one of Cortés’ first mistresses, but he left her shortly after the birth of their son, Martin. Marina later married a Spanish soldier and died relatively young. Lisa Sousa, one of the authors of the exhibit catalog, suggests that “Sixteenth-century Indigenous histories and images emphasized Malinche’s roles as translator, co-leader of the Conquest, and evangelizer.” Thus, in the first 100 years after the Conquest, there was no stigma associated with her role in one of the world’s most dramatic conquests, a remarkable clash of cultures and societies.

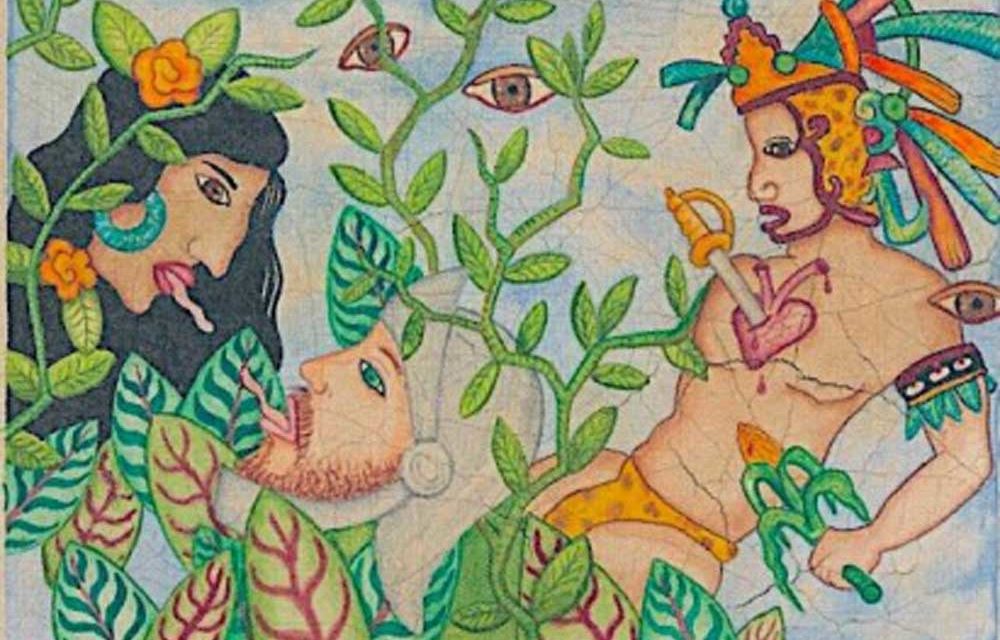

Two major artists of the post- Mexican Revolution era, Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco, gave Malinche new fame in the 1920s and 1930s. The murals of Rivera and Orozco are perhaps the most famous ever done in Mexico. These artists portrayed the Conquest of Mexico as one of the most monumental events in Mexican history. In their paintings, they portrayed Marina next to Cortés. At the beginning of the 20th century, she was one of Mexico’s most famous women figures. She is easily recognizable with her huipil dress, long black hair, and Indian jewelry.

Artists made her famous, but writers took aim at her persona. Octavio Paz, Mexico’s first winner of the Nobel Prize in literature, paid special attention to Marina, whom he helped to popularize as La Malinche, or the mother of “los Chingados” [the screwed]. In Paz’s essay, “The Sons of La Malinche” in The Labyrinth of Solitude and the Other Mexico, Paz is sadly misguided in his interpretation of the Conquest. He wrote: “It is true that she [Malinche]

gave herself voluntarily to the conquistador, but he forgot her as soon as her usefulness was over. Marina becomes a figure representing the Indian women who were fascinated, violated, or seduced by the Spaniards.”

Writing in the 1950s, Paz somehow had not

considered that for centuries Mexican women, especially Indian women, had been enslaved, raped, and oppressed. Beginning in the 1970s, Chicanas took the lead in challenging the Paz narrative about Marina. Chicana artists also began reinterpreting the imagery–from one of a fallen woman to one more associated as a survivor. Catalog authors Victoria I. Lyall and Terezita Romo note that these Chicana writers “saw themselves in the images of this woman, who had survived as best she could, despite the violence, trauma, and abuse she suffered at the hands of others.” The exhibit includes works by well-known Chicano artists including Cesar Martinez, Santa Barraza, Cristina Cardenas, Terry Sandoval, and Vicente Telles.

La Malinche is a complicated story, as it should be given its five hundred year history. SAMA curators added that “Malinche and her life story have shaped contemporary discourse on gender politics, Indigeneity, mixed-race identity, and language in the Americas, most notably in Mexico.” San Antonians must see the exhibit and hear the impressive presentation provided by SAMA Curator Lucia Abramovich Sanchez. I also encourage everyone to read the excellent essays in the beautiful exhibit catalog, La Malinche published by Yale University Press.

La Malinche Exhibit Challenges Historical Interpretations Interpretations