The borderland artists of the El Paso-Isleta-San Elizario region, known as the Mission Valley, represent nearly 350 years of history and tradition. Spanish colonizers first arrived in that region in 1598 when Juan de Onate and 129 soldiers and families crossed the Rio Grande on their way to conquer the current territory of New Mexico. Sixty years later, a Franciscan, assisted by Manso Indians, led the construction of the Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe Church in 1659 on the southern banks of the Rio Grande in present-day Juarez. The church paintings and architectural motifs represent the first Latino art renderings of the borderlands.

The Pueblo Indians residing near present-day Albuquerque and Santa Fe resisted the Spaniards from the start and fought them for decades before driving them out in 1680. When the Spanish military defense fell to persistent Pueblo Indian resistance, the Spaniards fled New Mexico toward the Rio Grande. The Tigua Indian allies followed the Spanish colonists. Together they settled in the Mission Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe in Juarez and the Corpus Christi de Isleta Mission south of El Paso.

The exodus from New Mexico resulted in desperation and fear, and thus we know relatively little about the actual construction of the Isleta Mission. Nonetheless, this mission served as a haven for Spaniards and Tigua Indians until the 1690s when the Spaniards returned to successfully reconquer New Mexico.

El Paso’s Mission Valley is significant to the origins of Latino art and culture. Latino art and architecture of the Valley were a vital part of the construction of Corpus Christi de Isleta in 1680, a mission serving perhaps the oldest religious community in Texas. Latino artists, initially Mestizo craftsmen from Mexico’s northern regions, created multiple forms of art devoted to religious themes. The art included retablos, religious paintings, church statues, sculptures and architectural motifs incorporated in the missions. To date, we know little of the identity of these pioneering artisans and masons who lived and worked in seventeen-century Juarez, Isleta, and nearby San Elizario.

San Elizario, founded in 1788 as a military fort, had a strategic military purpose. Spanish and Mestizo soldiers defended the caravans that traveled along the Camino Real from Chihuahua to New Mexico and south toward the missions adjoining the pueblo of present-day Presidio. Today San Elizario is a small community of 14,000 residents where the presidio chapel continues to serve as an active Catholic parish.

Prior to the twentieth century, the artists of the Mission Valley toiled in obscurity. Although most religious objects have been preserved, other material artifacts such as pottery, leather saddles, and carved metal spurs have been lost. The disappearance of so many historical artifacts illustrates why the current efforts by Latino artists in San Elizario of the Mission Valley are so important.

Gaspar Enriquez is San Elizario’s best-known artist and cultural ambassador. Several of his works have been recently acquired by the Smithsonian’s American Museum of Art. Enriquez was away in Riverside, California the week I visited El Paso [June 15]. He participated in the opening of “The Cheech” Museum where his work is among the Chicano art collected by Cheech Marin, the famed actor. Enriquez’s work can also be seen at the El Paso Museum of Art, where a twenty-five-foot portrait of the El Paso “Cholo” culture titled “Color Harmony en La Esquina” by Enriquez welcomes visitors entering the first floor.

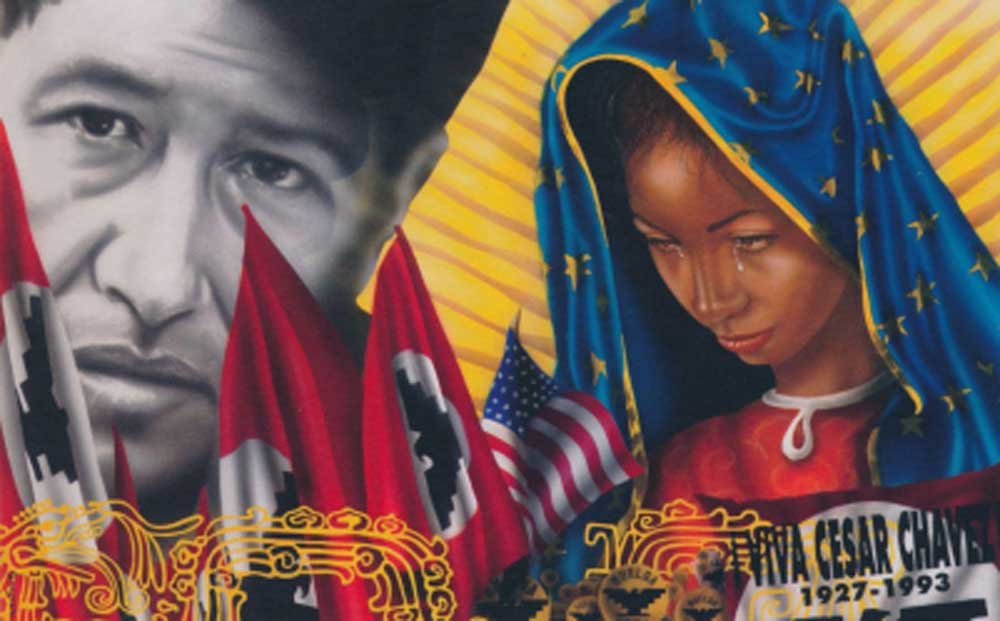

The main exhibition hall of the El Paso Museum of Art features Enriquez’s 12 paintings titled “Elegy on the Death of Cesar Chavez. The paintings include a portrait of Chavez leading union workers on strike, imagery that captures the arrest of farmworkers on strike, and portraits of children whose death was attributed to the use of DDT sprayed on the crops their families picked. Several images show families and young people who aspire to a better life. During the height of Chavez’s organizing efforts in the 1960s and 1970s, most children did not finish high school, and farmworkers had a life expectancy of 49 years, far below that of average Americans.

Enriquez was born in El Paso’s famed Segundo Barrio. After graduating from high school, he followed the path of many young men from that barrio who migrated to California. California offered better-paying jobs and educational opportunities for Latinos from Texas. Enriquez worked as a machinist and took evening classes at East Los Angeles Community College. He returned to El Paso in the late 1960s and earned a B.A. in Art from the University of Texas-El Paso [UTEP] in 1970. He credits three El Paso native-born artists, Manuel Acosta, Mel Casas, and Luis Jimenez for inspiring his artistic development.

Following his graduation from UTEP, Enriquez found an art teaching position at Bowie High School, aka “La Bowie.” At La Bowie Enriquez found the subject matter that mirrored his early experiences in El Segundo Barrio. Myrna Zanetell of El Paso Inc. described that imagery as “unsmiling faces, ‘shades,’ tattoos, crossed arms or legs, belligerent stances–all are the components of the ‘barrio attitude’ that Enriquez so successfully captured in his art.” When asked why their attitude was so confrontational, Enriquez replied, “You wouldn’t smile if you did the things those kids often have to do just to survive.” [Zanetell]

Enriquez taught at Bowie High School for 33 years, retiring in 2002. Over those three decades, his art evolved. In the 1980s he gave up using the traditional paintbrush and began painting with an airbrush. In the 1990s Zantetell wrote that Enriquez utilized the air-brushing process to create “cut out life-sized individual portraiture rendered in black and white explaining that this monochromatic palette characterized life in the barrio conditioned by deprivation, lack of hope, and difficulty in achieving their potential.”

San Elizario is seventeen miles south of El Segundo Barrio. While some residents date the town’s origins to 1598 when the conquistador Juan de Onate crossed through El Paso del Norte, historical evidence places the town’s founding after nearby Corpus Christi de la Isleta in 1680. San Elizario is an old colonial town with much history. Enriquez, whose studio and art gallery is located in a restored colonial building in the Placita Madrid, has joined other Latinos over the past 20 years in the restoration of the historic colonial town of San Elizario. His art and commitment to the community keep the borderlands’ history and culture vibrant.

Latino Borderland Artists In El Paso’s Mission Valley Keep History and Culture Vibrant