Several years ago I wrote about Liliana Wilson, a remarkably talented Latina immigrant artist who has spent her entire adult life in Texas. I wrote that Wilson represents the quintessential ideal for International Women’s Day, a day when women are recognized for their achievements “without regard to divisions, whether national, ethnic, linguistic, cultural, economic or political.”

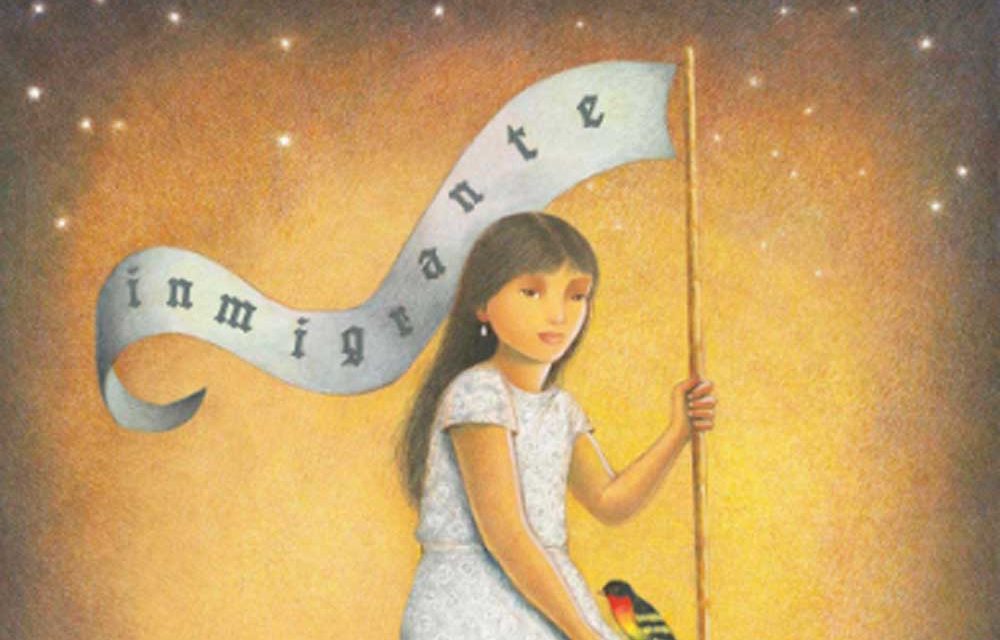

Liliana was born in Valparaiso, Chile, and lives and works in Boerne, Texas. She is known for portraying immigrants and working-class people in her art. As a first-generation Latina immigrant, she addresses her concerns for the plight of humanity by looking at global issues: migration, climate change, and social justice. She reminds us, for example, that immigration is not just an American issue, it is a worldwide phenomenon and the media provides daily evidence of tragic events affecting migrants. Every continent and most countries of the world are affected by the large-scale movement of people.

I spent a summer in Chile in the mid-1960s thanks to a student exchange program sponsored by the University of Texas–Austin and the U.S. State Department. I have returned to Chile on several occasions in the last few decades, re-visiting Santiago, the capital, and remote towns in the northern region. The greatest disappointment of my Chilean visits was the relatively small number of native artists in their museums and in the major art galleries. In contrast, Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina have a far greater number of internationally known artists.

That Liliana did not study art in Chile is of no surprise to me. She would have found few art role models, and fewChilean women in the art world, especially during her teen and young adult years. Liliana developed artistically while living in Chile; however, her interest during her young adult life lay in the study of law. After finishing legal studies, she chose to emigrate to the United States.

During the 1970s Liliana witnessed the exodus of thousands of Chileans, the majority seeking refuge in Europe and North America. Liliana’s working-class background sensitized her to the struggles of low-income workers. She was raised in a family that struggled to support the family’s five children. Nonetheless, she persevered and managed to study law. Her excellent educational background and professional attainment enabled her to emigrate to the United States in the late 1970s.

Much changed for Liliana after moving to Texas in the late 1970s. In Austin, she befriended Cynthia and Libby Perez, two sisters who are known for their social activism and appreciation of Latino artistic creativity. In the late 1980s the Perez sisters emerged as vocal champions and exhibitors of local Latino art and the creators of La Peña, a Latino non-profit arts organization. With the encouragement of Cynthia Perez, Liliana began to paint again. Her initial works captured the horror of Chile’s tyrannical government and the abuse of power by the military in Chile.

In Austin, Liliana also met Sam Coronado, then one of America’s leading Latino art printers. Coronado was also an artist and art instructor at the Austin Community College where Wilson studied with art instructor José Treviño. Coronado saw great talent and creativity in Wilson and offered her assistance in the creation of several serigraphs at his art studio, Coronado Studios. Her serigraphs include images of women struggling with identity, lack of inclusiveness, and their demands for equality with men.

Coronado Studios was located in the barrio of East Austin and served as a cultural oasis for artists like Liliana. There, in the small but cozy Coronado workshop, Liliana met and worked alongside other artists from the United States and Mexico. With the assistance of these barrio printers, Liliana began her serigraphic experimentation. She has now achieved international status and returns to work with other local artists as a mentor and collaborator. Sam Coronado, who passed away seven years ago, noted to me that Liliana was among several artists working in the studio who dedicated themselves to exploring third-world themes related to poverty, inequality, and injustice. One of her limited editions from this studio, “Mi Niña Triste,” shows a profile of a young girl sitting alone with her head bowed in her hands, suggesting solitude and even hopelessness.

In less than twenty years, Liliana has emerged as a major contributor to Latino artistic expression in theAmericas. Her work has always championed social justice and opposition to oppression and violence. Today, she continues to touch on global themes and one finds in many of her works compassion for the poor, the hungry, and those living under oppressive political regimes. Trinity University professor Norma E. Cantu [Editor of Ofrenda: Liliana Wilson’s Art of Dissidence and Dreams] published an excellent collection of essays in 2014 on Liliana’s artistic journey.

Wilson is unique in the world of Latino art. As a native of Chile, she represents a small minority among a rising and dynamic Latino population. While she seems driven by a desire to speak for those without access to power and wealth, Liliana’s work also shows a desire to understand the common individual’s struggles with despair, fear, and hopelessness. As she moves among different themes and mediums, Liliana inspires young Latina artists across the wide divide of North and South America and beyond. Her art is destined to be appreciated for years to come.

Liliana Wilson: An Immigrant Latina Artist