I was born in San Antonio, Texas and grew up on the eastside of SA, basically the predominantly African-American community of the city. We lived in the back of Dad’s barbershop in a small strip center at the intersection of Nolan & Pine Streets. Dad split the rented space in half, the front was the barber shop and the back half served as our tiny home.

Downtown SA was just 9 blocks away. Often Mom & I would catch the Beacon Hill bus to go downtown or walk the distance because according to Mom, “It’s a nice day to walk downtown.”, but mostly as a result of us having missed the bus.

On Nolan Street, closer to downtown and on our walking path was St. Peter Claver Catholic Church. It was a small humble church, built in 1888 along with a convent and school.

The church and school for African-Americans, was founded by Mary Margaret Healy Murphy, an Irish widow from Corpus Christi who had moved to San Antonio. Healy Murphy suffered many indignities and persecution from those opposed to the construction of the facilities located at Live Oak and Nolan Streets. The school and church were to be built in a prominent white neighborhood.

In an upcoming article I will elaborate more on Healy Murphy’s trials and tribulations. The Sisters of the Holy Spirit and Mary Immaculate, the order which Healy Murphy founded, are now seeking her canonization. San Antonio may one day boast of having its own saint!

San Antonio can be proud, because St. Peter Claver was the first Catholic church and school for Black people in Texas. Back then, even the Catholic Church was prejudiced and would not allow African-Americans into churches, those that did, would have a “Negro Section” in back of the church. It was also unheard of to educate African-American children in Catholic schools.

The church was named for St. Peter Claver, a Jesuit saint canonized the same year in 1888. Peter Claver spent his life working to alleviate the suffering of African slaves aboard Spanish slave ships in the New Kingdom of Granada.

There wasn’t a Catholic church Mom could not pass by without entering it to visit and pray. Many times we would stop at St. Peter Claver Church. As always, before Mom walked in, if she did not have her veil, she would place a white handkerchief or kleenex on her head secured by a bobby pin. A sign of reverence before she entered the House of God.

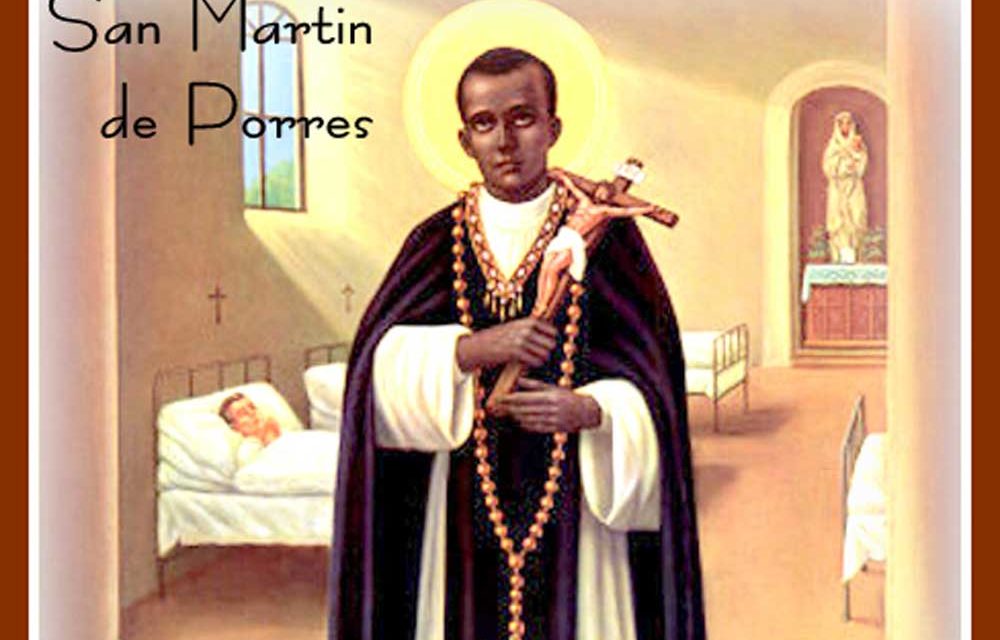

In the back of St. Peter Claver’s Church was a small statue about 2 1/2 ft. high. It was of a black man dressed in black & white robes. At the base was etched, “Blessed Martin de Porres”. Mom would always kneel and pray to him.

I had never seen a statue of a Catholic black person in any church. Mom told me, “Son, this is Blessed Martin De Porres, he is going to become a saint one day.” She’d continue whispering her prayers to him.

In May 1962, as the struggle for civil rights heated up in the United States, Martin de Porres was canonized by Pope St. John XXIII. He was already one of Mom’s favorite heavenly lawyers. One day she brought home an image of Martin and framed it in an old Mexican wood carved frame my grandfather had given her. As I grew older I gave Mom a bust of Martin. Mom’s special devotion to Martin was that he helped people of color and in his early days he was a barber, just like my dad.

Forever the humble San Martin de Porres holds a place of prominence in our home.

I owe a debt of gratitude to my parents for teaching me about my Catholic faith, the communion of saints and especially how to be colorblind when it comes to humanity.

Herewith is the story of San Martin de Porres from Franciscan Media….

“Father unknown” is the cold legal phrase sometimes used on baptismal records. “Half-breed” or “war souvenir” is the cruel name inflicted by those of “pure” blood. Like many others, Martin might have grown to be a bitter man, but he did not. It was said that even as a child he gave his heart and his goods to the poor and despised.

He was the son of a freed woman of Panama, probably black but also possibly of Native American stock, and a Spanish grandee of Lima, Peru. His parents never married each other. Martin inherited the features and dark complexion of his mother. That irked his father, who finally acknowledged his son after eight years. After the birth of a sister, the father abandoned the family. Martin was reared in poverty, locked into a low level of Lima’s society.

When he was 12, his mother apprenticed him to a barber-surgeon. He learned how to cut hair and also how to draw blood (a standard medical treatment then), care for wounds and prepare and administer medicines.

After a few years in this medical apostolate, Martin applied to the Dominicans to be a “lay helper,” not feeling himself worthy to be a religious brother. After nine years, the example of his prayer and penance, charity and humility led the community to request him to make full religious profession. Many of his nights were spent in prayer and penitential practices; his days were filled with nursing the sick and caring for the poor. It was particularly impressive that he treated all people regardless of their color, race or status. He was instrumental in founding an orphanage, took care of slaves brought from Africa and managed the daily alms of the priory with practicality as well as generosity. He became the procurator for both priory and city, whether it was a matter of “blankets, shirts, candles, candy, miracles or prayers!” When his priory was in debt, he said, “I am only a poor mulatto. Sell me. I am the property of the order. Sell me.”

Side by side with his daily work in the kitchen, laundry and infirmary, Martin’s life reflected God’s extraordinary gifts: ecstasies that lifted him into the air, light filling the room where he prayed, bilocation, miraculous knowledge, instantaneous cures and a remarkable rapport with animals. His charity extended to beasts of the field and even to the vermin of the kitchen. He would excuse the raids of mice and rats on the grounds that they were underfed; he kept stray cats and dogs at his sister’s house.

He became a formidable fundraiser, obtaining thousands of dollars for dowries for poor girls so that they could marry or enter a convent.

Many of his fellow religious took him as their spiritual director, but he continued to call himself a “poor slave.”

Martin de Porres is often depicted as a young mulatto friar wearing the old habit of the Dominican lay brother, a black scapular and capuce, along with a broom, since he considered all work to be sacred no matter how menial. He is sometimes shown with a dog, a cat and a mouse eating in peace from the same dish.

Martin de Porres is the patron saint of African-Americans, barbers, hairdressers, race relations, radio and social justice.

Rick Melendrez, is a native San Antonian. Melendrez considers himself fortunate to have been born in San Antonio, just 3 blocks from the San Antonio de Valero mission (the Alamo) at the former Nix hospital on the riverwalk and to have attended Catholic grade school on the southside and on the riverwalk.

Catholic education is very close to his heart. Melendrez attended St. Michael’s for five years (1960-65) and then attended St. Mary’s School on the riverwalk (1965-68) and onto Cathedral high school in El Paso, Texas.

He is the former publisher of the El Paso Citizen newspaper and former chairman of the El Paso County Democratic Party. He writes a page on Facebook titled “Sister Mary Ruler, Growing Up Catholic In San Antonio”. Everyone is invited to read about his San Antonio of the 1960’s.

You may contact Melendrez via email at rickym8241@aol.com or by phone, 915-565-1663 (landline).