The Art of Jacinto Guevara: Documenting Unique Latino Culture Earth Day, Godfather movies, and disco music fascinated young people. The advent of the computer revolution marked a major change in society.

For Latinos, the decade included significant events as cities across the Southwest experienced school walkouts, and California farmworkers won important union and legislative policy victories. Talented youth introduced Chicano poetry, plays, and film, and universities developed Chicano Studies classes and programs.

Chicano artists who grew up during the seventies witnessed great transformations as they saw for the first time a flowering of their own artistic cultural creations. Jacinto Guevara of San Antonio emerged as one of the fortunate individuals who rode the early waves of this artistic movement. His story provides some important insights into one of the most significant eras of Chicano artistic creativity.

From an early age Jacinto Guevara discovered that art represented an important means of communicating. Guevara came of age artistically during the early 1970s while attending Belmont High School in East Los Angeles. At the time, few Latinos went to museums but most grew up surrounded by commercial art, usually in the form of billboards and posters. Significantly the early expressions of Arte de La Raza appeared in public art.

Chicano art originated with the mural movement in California. Art historians place the birth of Chicano art between 1968-1973. Guevara was a teenager when Chicano artists painted a mural at the headquarters of Cesar Chavez’ United Farm Workers Union in Del Rey, California. Some of the earliest Chicano murals originated in the heart of East Los Angeles, in close proximity to Guevara’s home.

When Joe and John Gonzalez decided to convert an abandoned meat market into an art gallery, they recruited two future Chicano art stars, David Botello and their brother-in-law Ignacio Gomez, to paint what UCLA art historians have identified as the first public Chicano mural in East Los Angeles. Muralism became the most prominent creative development of Chicano art.

Guevara enrolled at California State University Northridge [CSUN] in 1975, a time when colleges throughout Southern California were reaching out to East Los Angeles students. Guevara had seldom gone to the San Fernando Valley, home of the Northridge campus, but he liked CSUN’ s Chicano Studies Program which was in its sixth year. He majored in Ethnic Studies and took classes with famed Chicano historian Dr. Rudy Acuna. Guevara loved music and joined the mariachi band headed by Professor Beto Ruiz. Guevara became a frequent art and cartoon contributor to El Popo, the

Chicano student newspaper founded in 1970.

After graduation from CSUN in 1980, Guevarra painted on a regular basis and also joined several musical bands. During these years, while Guevarra remained an early aficionado of the emerging Chicano murals in his community, he focused on his drawings and canvas painting. He bought one of his first canvases for three dollars and spent a half day cleaning it.

Guevara worked at his art but could not seem to make the right connections to get his paintings in galleries and had a difficult time making a living as an artist. An invitation in 1990 by the established B-1 Galleries in Santa Monica offered him some hope. He was invited, along with several of the leading East Los Angeles artists, including Frank Romero, Wayle Alaniz, and Paul Botello to exhibit his paintings. Although Latino art was gaining in popularity, few of the paintings sold. After that show, Guevara began to think of leaving Los Angeles and was attracted to San Antonio because of the city’s thriving Chicano culture.

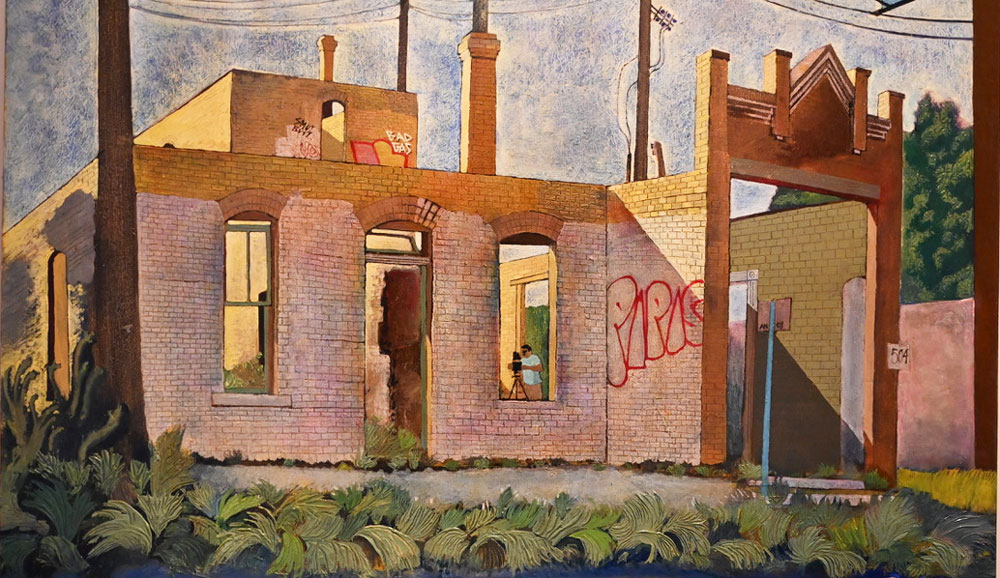

Guevara found the San Antonio weather suitable for his preference of open air painting, or what the French called “plein air.” Some of his favorite subjects included abandoned railroad stations and warehouses. He delighted in finding unique subjects for his paintings, such as icons and buildings in San Antonio that most observers

had overlooked. Many of his paintings reflect the older sections of the East and West side of town. He looked for old houses, residences that did not necessarily catch the public’s attention. These residential structures were simple, but attractive. He told me that these houses “weren’t necessarily pretty.”

In 2016 Lewis Fisher published “Saving San Antonio: The Preservation of a Heritage.” It told a story of the San Antonio Conservation Society’s organized efforts to save historical houses from destruction. Guevara is also “saving

San Antonio” through his paintings. His work captures the essence of the city, areas where not all the houses and buildings are spectacular, but they contain meaning and beauty for their owners. Guevara’s structural portraits, such as that of the 1880s building, “Liberty Bar,” which became a hang out for many Chicano artists, capture a heritage that makes San Antonio unique.