One hot summer day in 1947 in San Antonio’s Westside, twelve-year-old Jose Esquivel knocked on the door of Porfirio Salinas, one of Texas’ leading landscape artists who was already a bright star among emerging native Latino artists of Texas. The young boy had been sent by his dad to Salinas’s home to cut the grass and help with other yard chores. Esquivel had never met an artist before, and he was immediately struck by the bluebonnet landscape canvases piled up in Salinas’s living room–a studio of a true master of Texas nature painting. Esquivel returned to the Salinas home many times to help with the yard work and other house chores. In the process, he also learned about art by talking to Salinas.

When Esquivel enrolled at San Antonio Technical and Vocational High School three years later, he made the decision to study art. The vocational schools of that era around the country taught only commercial art, but students were also encouraged to learn about fine art. [I know that school program well since I also attended Tech High School]. Esquivel excelled in commercial art, and following his graduation he received a scholarship to study at the Warner Hunter School of Art in San Antonio’s La Villita district. Hunter personally assisted low-income students with scholarships. Esquivel studied with Hunter for five years learning line drawing, watercolor, and oil painting.

In 1968 Esquivel joined a collective of ten San Antonio artists who chose to identify themselves as Chicanos. Esquivel documented this art movement, including the preparation of the first Chicano art exhibits in Texas and the Midwest.

In their meetings, the members frequently debated identity issues of being Mexican, Mexican American, or Chicano. They also debated what kind of art represented La Causa, and how best to make their purpose and ideas known. Smithsonian curators with the Latino Museum recently connected with Jose Esquivel requesting all of his papers for their archives, as well as examples of his art. Esquivel’s artistic journey is an important part of Chicano art history.

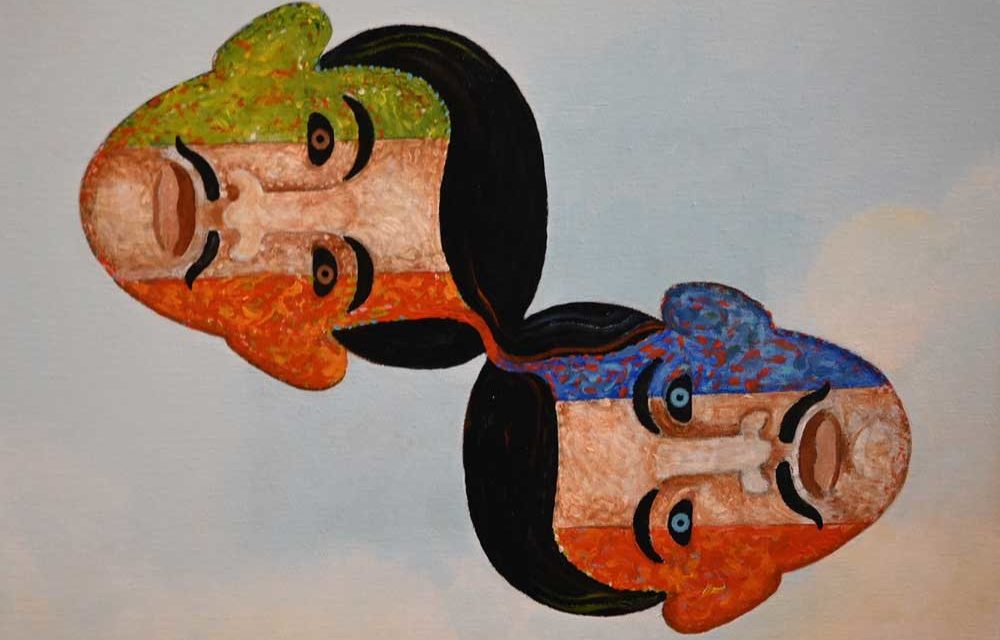

Esquivel’s art at the Centro Cultural Aztlan, principally of the past 25 years, aptly shows his creativity and exceptional ability to interpret the Chicano experience in America.