In my fifty years of academic life, I have interacted with hundreds of scholars and graduate students. When I first met Americo Paredes I knew I had encountered a true “Renaissance man.” Don Americo’s career included journalism, radio broadcasting, scholarship, and college teaching. He spoke and wrote Spanish and English with ease and was among the first to author scholarly books about Texas-Mexican Borderland folklore and Mexican American anthropology. He published several novels as well as books on his poetry. He sang and played the guitar exceptionally well.

I first learned of Americo Paredes’ outstanding books, in particular, With His Pistol in His Hand, when I began teaching Chicano History in 1970. In the fall semester of 1970, I was hired to teach history for the Chicano Studies Department at San Fernando Valley State College in Southern California. The department, founded by Dr. Rodolfo Acuna, was but a year old and thanks to Acuna’s excellent teaching, enrollment in the Chicano history classes more than doubled. Paredes’ With His Pistol in His Hand was one of the more popular books that Dr. Acuna suggested.

I initially became familiar with Americo Paredes’ reputation when I attended UT Austin in the early 1960s. Several of my friends, including Raymund Paredes and Jose Limon, took his classes, but I never had that good fortune. At the time UT Austin’s two best-known Mexican American professors were Americo Paredes who taught English, Folklore, and Anthropology, and George I. Sanchez, a distinguished education professor. Carlos Castaneda, perhaps the first Mexican American to earn tenure at UT Austin’s College of Liberal Arts, taught full-time in the History Department over the years 1946-1958.

My personal interactions with Don Americo, as he was known to many of his friends, began in 1977. That year I was teaching at the University of California San Diego [UCSD], and I received a small grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to sponsor a conference on Mexican American Studies.

I asked Americo Paredes and Tomas Rivera to serve as mentors and principal discussants at the conference.

In preparation for this conference, I invited Don Americo to the UCSD campus where I served as a member of the history faculty and Chair of Chicano Studies. Over his three-day stay, Don Americo and I toured the campus, visited Chicano community organizations, and explored Tijuana, Mexico where we had lunch. Our in-depth conversations began that day. Professor Paredes shared with me his thoughts about the borderlands, noting, for example, some of the differences between South Texas and the Southern California border of Tijuana-Mexico. One difference was that the border town of San Diego in the mid-1970s still had a large Anglo population which numbered nearly 600,000 of a total population of 700,000. Latinos were estimated at slightly less than 100,000 or just under 20 percent of the San Diego border population. In contrast, Mexican Americans comprised the vast majority in all the Texas-Mexican border towns stretching from Brownsville to El Paso.

Don Americo was born in the Texas Borderland town of Brownsville in 1915. He grew up speaking Spanish and hearing corridos and border stories from his father. His community was nearly 90 percent Mexican-American during that era as it is to the present day. As a high school student, young Americo won prizes for his poetry and published poems in La Prensa. He attended the local

community college and worked as a reporter for the Brownsville Herald.

Paredes told me that in the 1930s he also hosted a radio show where he was spontaneously called upon to sing songs listeners requested. When I asked him how many songs he had memorized, he responded–over 500. Many were the border ballads and corridos that he had learned growing up. He also recounted a story about meeting the Tejana singer Chelo Silva on the radio show. They had a brief courtship and married soon after.

Don Americo served in the military following the 1941 attack on U.S. ships at Pearl Harbor. The Army put his literary skills to good use assigning him to write and edit the Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper. Don Americo and Chelo Silva divorced during the war years due to the difficulties of separation from home for

extended periods. After the war, Paredes remained in the service and was stationed in Japan with a new assignment–covering Japanese war crimes.

On numerous occasions, Don Americo mentioned the story about meeting his future wife Amelia at the USO in Toyko. He was intrigued by her knowledge of the Spanish language. Her language skills were a result of her father’s diplomatic assignment in Uruguay before the war years. While in Montevideo, her father had met and married Amelia’s Uruguayan mother.

Don Americo and his new wife returned to Texas and moved to Austin. He enrolled at UT Austin where he finished his BA, MA, and Ph.D. in six short years. His first teaching post was in El Paso, but after a year at UT El Paso, he was offered a job in the English Department at UT Austin.

In 1979, Don Americo invited me to apply to be the director of Mexican American Studies at UT Austin, a program he had started in 1970 with education professor Dr. George I. Sanchez. Don Americo sent my resume to the UT History Department with hopes that they would interview me. The Department faculty responded with a request for an interview with me and in 1980 the Department hired me. I became only the second Latino,

after Dr. Carlos Castaneda, to teach in the more than 80 member UT Austin History Department.

Over the decade of the 1980s, as I taught History of the Southwest, Civil Rights, and Urban History, I visited on a regular basis with Don Americo. In the late 1980s, we made an informal pact to have coffee together once a week. We were often joined by Latino professors from other departments including Rolando-Hinojosa-Smith, Ramon Saldivar, David Montejano, and Manuel Pena. The Paredes family also hosted small dinners for the Mexican American faculty, and we became friends with Amelia and her mother who lived with them.

It was in those informal settings that I learned first-hand about Don Americo’s life and his journey to becoming one of the most respected Mexican American scholars in America. Don Americo retired in 1984 but remained connected with colleagues in English and Anthropology. Excellent works on his life have been published by professors Jose Limon, Ramon Saldivar, Ben Holguin, and Manuel Medrano.

Don Americo passed away in 1999 at the age of 83. At the request of the family, I arranged a Despedida at a large conference space on the UT Austin campus. The commentary by his colleagues and friends proved that Don Americo Paredes was more than a “Renaissance man”–he was a beloved human being, scholar, mentor, and teacher.

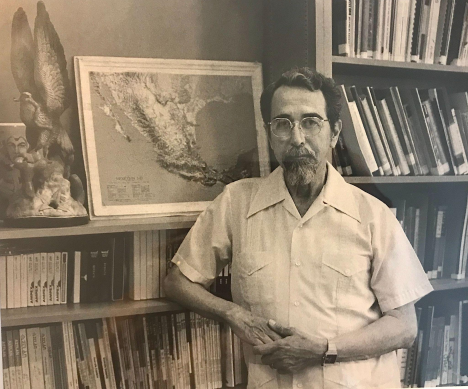

Americo Paredes: Scholar, Poet, Musician, Teacher, and Mentor