Luis Jiménez, a trail blazing artist of the U.S. Mexico borderlands, grew up in El Paso learning as a young boy how to spray paint, weld, and mold glass. His father’s electric sign company, located a few short blocks from the Rio Grande, specialized in neon signs, a trade and business that the senior Jiménez hoped to pass on to his talented son. The Jiménez family home was also located in the historic ”Segundo Barrio,” a large Mexican American neighborhood only blocks from the international border and Juárez, Mexico.presents and preserves our culture, traditions and talents of yesterday and today.”

Jiménez grew up in a Spanish-speaking household, one of the many in El Paso’s bicultural and bilingual community. In the 1960s El Paso and Juarez were often described as one of the “twin cities” of the border. The interconnectedness of the two communities gave both cities a unique borderland flavor. The U.S.-Mexico border entry gates were less intrusive in the mid 20th-century and families and visitors from each side of the border crossed easily. The elder Luis Jimenez conducted his sign business on both sides of the border. Customers paid him in pesos as well as in dollars. The younger Jiménez crossed the border often to catch a bull fight or listen to mariachi music in Juarez’s many colorful cantinas. These borderland experiences influenced his later art.

After completing high school, Jiménez made a

monumental decision to study architecture at the University of Texas in Austin with the intent of seeking a different career path from that proposed by his father. His interest in architecture waned and by 1964 when he graduated, he had decided to become an artist. His interest extended beyond painting and drawing, but unsure of what medium to pursue creatively, he applied to study in Mexico City.

Jiménez arrived in Mexico just as the city had learned of its selection to host the 1968 Olympic Games. In Mexico City, the leading art capital of Latin America, Jiménez found himself surrounded by a vibrant artistic culture. On the UNAM campus where he studied, bold and colorful murals by David Alfaro Siquiros dominated one of the entryways. Juan O’Gorman’s mosaic tiles on the entire exterior of the UNAM famed library stood as an artistic tour de force.

While in Mexico City Jiménez also made a point of

studying the murals of Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco as well as visiting the Aztec pyramids. In later years Jiménez applied some of the historical themes he discovered during his days in Mexico. His painting of “Southwest Pieta,” for example, shows the influence of Mexican mythology with the portrayal of an Azteca maiden in the arms of an Aztec warrior. In the background, Jiménez included Mexico’s two tallest volcanic mountain peaks.

After his stay in Mexico City, Jiménez journeyed to New York City where he joined a highly dynamic art scene heavily influenced by pop art. Jiménez was one of many struggling artists living in New York City during the late 1960s. During the day he worked in the Bronx teaching art to young people of color who could not afford a traditional art education. In the evenings, Jiménez constructed brightly colored fiberglass and epoxy sculptures that criticized “the dominant culture and the effects of racism.”

Jiménez challenged traditional notions of beauty arguing “the Media seemed determined to exclude anyone of color. The Mexican American or anyone who is not blond and blue-eyed is super aware of it, because he does not fit this image.” Jiménez, art historian Eva Cockcroft wrote, like [Mel] Casas, “attacked racial stereotypes in his art not only through subject matter, but indirectly through a style that glorified the kitsch in Chicano artifacts and color preferences.”

Numerous controversies arose regarding Jiménez’s art, and, as is often the case with abstract art, various interpretations questioned the meaning of his art. While living in New York, Jiménez constructed a seven-foot-tall Man on Fire bronze sculpture. Jiménez acknowledged to the University of Arizona Museum of Art staff that the piece had been influenced by one of Orozco’s most famous paintings, Man of Fire, completed at the Hospicio Cabanas in Guadalajara, Jalisco.

Jiménez, relying on a legend that Aztec Chief Cuauhtémoc had been tortured by the Spaniards in the midst of the conquest of Mexico, created a man on fire sculpture. Reviewing an exhibit of Orozco’s work in England catalog authors wrote that Orozco’s “Man of Fire” figure was “hard to read” in that it was “both disintegrating and seems to rise like a phoenix from the ashes.” Orozco’s “Man of Fire” mural is in part a metaphor for the theme of social struggle—the central theme of Jiménez’s work.

Jiménez’s comments to writer Jonathan Yorba, in a Smithsonian publication, Arte Latino, reveal that there is more complexity to the meaning of the sculpture Man on Fire. Jiménez told Yorba that his sculpture “memorializes the disproportionately large numbers of Chicanos who were drafted into the military and sent to Southeast Asia.” Jiménez was influenced by “watching television in horror as Vietnamese monks set themselves on fire in protest to the war.” Jiménez explained that the sculpture, “on a universal level, serves as a visual symbol of courageous action in the face of oppression.”

Jiménez left New York for New Mexico in 1972 following a commission he received from the Donald B. Anderson and Roswell Museum and Art Center to complete two large

sculptures titled Progress I and Progress II. The seventies were productive years for Jiménez as he received two awards from the National Endowment for the Arts. With a NEA commission with the City of Houston, Jiménez produced the Vaquero sculpture. The controversial Mexican vaquero held a large six-gun pointed in the air. The decision to place the sculpture in the center of a Hispanic park sparked resistance from residents who opposed guns. Jiménez’s Vaquero was moved to Washington, D.C. where it greets visitors to the entry of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Another sculpture produced with a NEA award with the City of Albuquerque, Southwest Pieta, also generated controversy as the community chose not to place the sculpture in Old Town, a historic part of the city. The sculpture was moved to another neighborhood in Albuquerque known as Martineztown, a short distance from downtown.

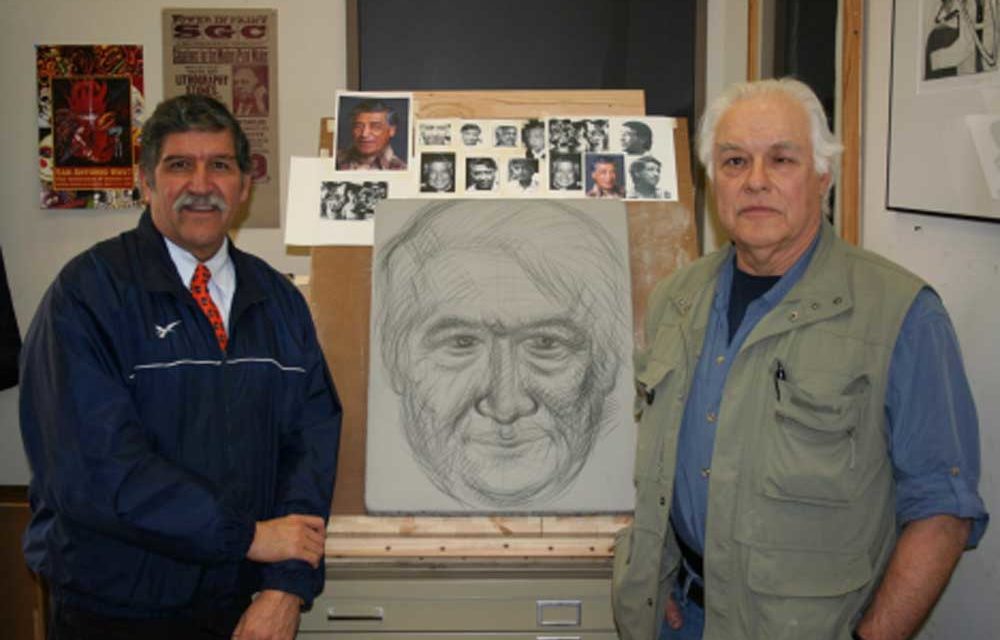

Jiménez worked the last quarter century of his life in New Mexico where he converted a school as his studio. On occasions Jiménez spent time in Texas, notably with Adair Margo’s art gallery in El Paso that handled his art sales. I had the opportunity to write about him in 1984 in Humanities Texas magazine when he exhibited at the Laguna Gloria Museum in Austin. Over the next twenty years Jiménez and I saw each other on an annual basis and I visited with him in San Antonio as he completed his last lithograph print, a portrait of Cesar Chavez, several months before he died. He was working on a large mustang sculpture for the Denver Airport in his studio in Hondo, New Mexico. On June 13, 2006 the massive 50 foot mustang slipped off a rope and fell on him crushing him to death.

The work of Jiménez lives on in his numerous sculptures, paintings, and lithographs on view in museums, and public spaces, as well as in numerous publications about borderland artists.

Luis Jiménez: A Latino Legacy of Borderland Cultures