Growing up in El Paso, Texas “with Juarez, Mexico in my backyard,” Latino artist Richard Armendariz found himself “saturated with a mix of romanticism for the new and old West American cultures and the iconography of an

ancestral past.” The mystique of the border region greatly influenced him, he added, “including mesas, honky-tonks, and big skies reaching as far as the eye can see.”

Armendariz grew up in a bilingual-bicultural world where family and schoolmates freely expressed themselves in mixed English and Spanish sentences. Today, Armendariz utilizes this border language, often referred to as code-switching, to add personal and cultural meaning to his paintings. Examples of his works with bilingual titles include “Ya Me Voy a Therapy,” “Tu Eres O

No Eres Mi Baby, ” as well as “The Way A Mi Corazon Es Un Bumpy Road.”

Armendariz’s interest in art began in the

mid-seventies when he took up drawing in pre-school. His active drawing and sketching continued through his teenage years. As a college student at UTSA, Armendariz knew he was attracted to the field of art, but his initial interests included art history and art therapy. He did not think seriously about making creative art until he began his Master of Fine Arts studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Once Armendariz began to paint, he relied on his borderland experiences as a way of expressing the topics of interest to him. Armendariz strongly identifies with both

American and Mexican cultures. He is especially fascinated with the people and animal life of the Rio Grande, the Mexican Sierras, and the arid landscape of West Texas.

Armendariz, who joined the University of Texas-San Antonio Art Department faculty in 2004, notes that his teaching and work is a result of coupling “traditional

techniques of painting, drawing, and printmaking with non-traditional methods of drawing or carving to achieve my esthetic.”

In 2017 Armendariz was selected as the first

Artist-in-Residence for The DoSeum, San Antonio’s Children’s Museum. Armendariz’s elaborate museum design, “The Dream Keeper,” included the creation of “a space of ‘dreams’ where children would relax and experience the exhibit both as spectators and as protagonists.” With the assistance of a local arts collective, ‘Art to the Third Power,’ that included artists Kim Bishop, Paul Karam, and Luis Valderas, Armendariz created over 50, 8-foot-high prints to build an “external facade with a surprise internal forest.”

On a smaller scale in his studio, Armendariz’s favorite medium is birchwood panels. He works with power tools to carve and burn his images into the surface of the wood as a base for his paintings and prints. He explained to art historian Teresa Eckmann that he has a preference for images “that have a cultural, biographical, and historical lineage.“

Armendariz also acknowledges that “Romanticism for the American landscape and the hybridization of Mexican, American, and indigenous cultures” often informed the content of his work. Examples of this are his large wood-carved paintings of a curandero and the buffalo of

the western plains. There is also an abundant portrayal of birds, rabbits, bears, buffalo, and coyotes carved into birchwood, all representing the past and present of his life in the Texas-Mexico borderlands.

In a stunning woodblock portrait of fellow El Paso artist and early mentor Luis Jimenez, Armendariz created

images painted on Jimenez’s face to tell of major episodes in Jimenez’s life. The bronco structure that fell on Luis Jimenez and killed him appears on the left side of the portrait. On Jimenez’s forehead, Armendariz painted an image of Talaca, a skeleton head representing Mexican-Indian imagery of death. On the bottom of Jimenez’s face is an image of a raven, a pet bird that Jimenez kept in his studio in Hondo, New Mexico. Armendariz, a friend of Jimenez, had visited the studio and had seen the raven, whom he described as quite mean.

Armendariz’s art celebrates the Texas Borderlands, a region that extends 830 miles from El Paso to Brownsville, nearly 200 miles on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico international boundary. Armendariz told art historian Eckmann that his work is “like the Southwest, something that looks like where I came from, a Bordertown.” He is also often drawn to conceptual themes “involving power dynamics, sentimental love, as well as passionate and explosive love.”

Armendariz creates many of his works with historical and contemporary commentary in mind. He noted that one wood-etched “painting depicted a condor and eagle locked in an embrace falling from the sky. In the composition, the birds of prey, symbolizing the United States and Mexico, will rise or fall together.” His romanticism about the West is reflected in one painting with the title “Confessions of a Singin’ Vaquero,” shown at Blue Star Contemporary Art Gallery in 2020.

Armendariz’s “Exodus” woodblock print, diptych ED of 5, 37″ x 85″, will be in the opening show of the new Cheech Museum in Riverside, Ca. in the Fall of 2022. His work is in the permanent collections of the San Antonio Museum of Art, the McNay Art Museum, the Denver Art Museum, and Ruby City in San Antonio, Texas. In addition, his work appears at the Bush International Airport. Armendariz also participated in numerous international exhibits, including Valdivia, Chile; Cuernavaca, Mexico; Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil; Bogota, Columbia; Bethlehem, Palestine; Oaxaca, Mexico; Berlin, Germany; Beijing, China; Sarajevo, Bosnia; and Guatemala City, Guatemala.

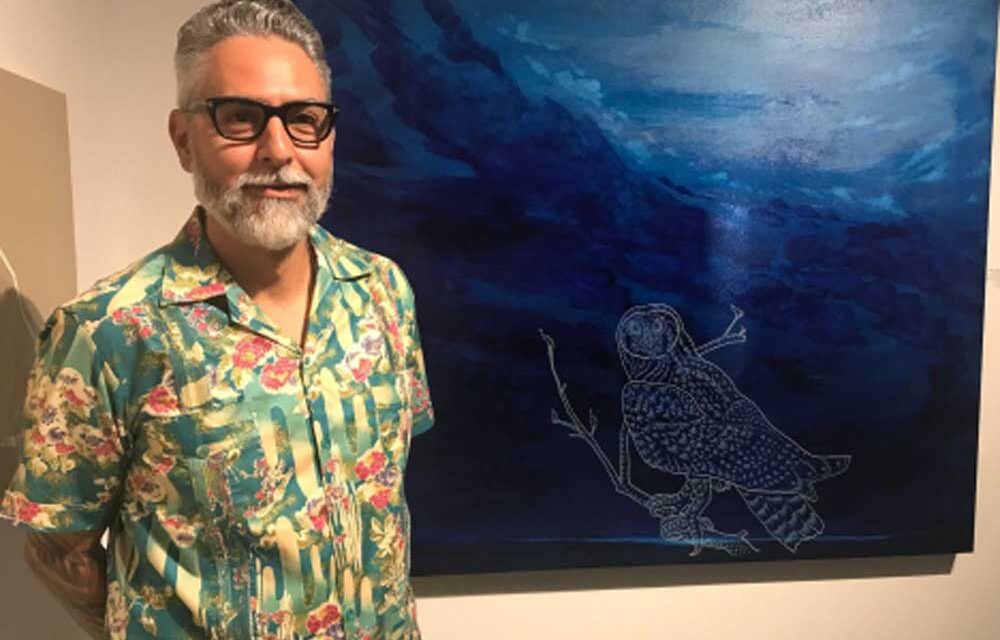

Richard Armendariz: Teacher, Artist, Borderlands Interpreter