This year marks the 100th anniversary of the beginnings of the Mexican mural movement. The idea for large-scale public art can be traced to Jose Vasconcelos, the Mexican Secretary of Public Education, who in 1921 commissioned the first mural painting in the building that once served as the chapel of San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City. What followed was monumental. Over the next three decades every state of the Mexican Republic, as well as major arts centers of the United States, France, Germany, and Russia, followed the Mexican model of government support for public art.

Vasconcelos, who was born in Oaxaca, lived for some years in Piedras Negras, on the U.S.- Mexico border. As a youngster, he walked a short distance across the international border to attend an American school in Eagle Pass. He later earned a degree in Law and served as Rector [President] of the National University of Mexico [UNAM].

Vasconcelos is credited for giving the university its popular motto, Por Mi Raza Hablará mi Espíritu [For my Race my Spirit Will Speak]. A brilliant essayist and philosopher, Vasconcelos is also recognized for his four

volume autobiographical books and as the author of La Raza Cosmica, a book in which he expanded his ideas of mestizaje, the blending of Indian and European races.

From the start, the Mexican mural movement attracted dozens of young painters, but by the mid 1920s, three artistic leaders emerged: Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, “Los Tres Grandes.” Rivera and Siqueiros had both studied in Europe. During Rivera’s last years in France, he had been instructed to visit and study the Italian frescos of Rome and Florence. Siqueiros had undertaken a similar artistic journey.

Upon the return of Rivera and Siqueiros to Mexico in 1921, they found highly enthusiastic support of their works in Vasconcelos. As Secretary of Education, Vaconcelos arranged for dozens of Mexican artists to paint murals on public walls. The muralists most often chose the themes of Indigeous civilization, liberation from foreign powers, revolution, labor exploitation, and class struggle. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco both journeyed to the United States either to find support for their work, or in the case of Rivera, to complete major mural projects in New York, San Francisco, and Detroit.

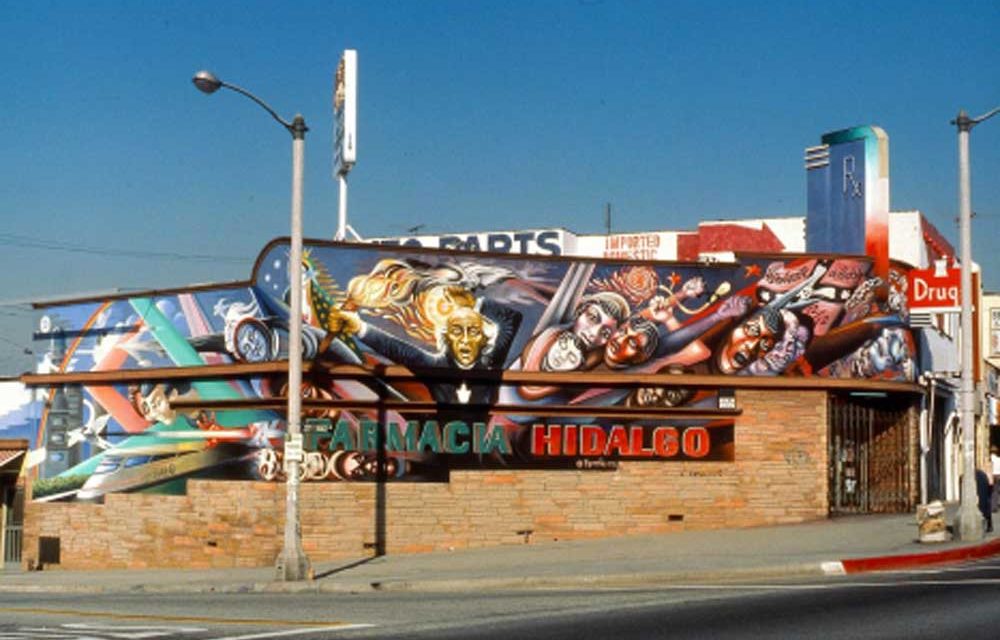

The Mexican muralists shaped the thinking and creativity of the early Chicano artists. Many of the initial Chicano murals paid homage to the intrepid “Los Tres Grandes,” Mexican muralists in the 1920s are credited with enhancing the recognition of Mexican Revolutionary leaders Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata. It is now officially a full century since the inspirational work of “Los Tres Grandes” began in Mexico City, but their legacy lives not only in Mexico, but in the hearts and minds of Chicano artists, young and old.

Mel Casas, one of the best known San Antonio artists, committed to painting as a career following his return to El Paso from military service in the Korean War. He served four years in the U.S. Army and received a Purple Heart for bravery. Upon his graduation from Texas Western University in 1956, Casas enrolled at the University of the Americas in Mexico City.

Casas was one of the earliest Chicano artists to travel abroad for the purpose of studying art. He chose Mexico, home of “Los Tres Grandes.” While Casas was influenced by the works of the Mexican muralists, he dedicated nearly all of his career to canvas painting. In 1961, Casas accepted an art teaching post at San Antonio College and taught art there for 29 years before retiring in 1990.

Casas is best known for his Humanscape series of 150 large-scale paintings [72”x96”] that he began in 1965 and completed in 1989. Gary Keller, author of the book Contemporary Chicana and Chicano Art, wrote that Casas “evinces a Chicano art aesthetic that is committed to a politics of self-determination and, on a visual level, self-representation” or the coming to terms with their Chicano identity.

Casas was one of the founding members of Con Safos, a San Antonio Chicano art collective that included Felipe Reyes and Cesar Martinez. With the assistance of

Chicano writer Tomas Rivera, the Con Safos group organized an art exhibition, the first ever by Chicanos in Texas, that traveled nationally in the spring of 1972. Casas’s Humanscape #38 was recently featured in the MCNay Art Museum’s tribute to Robert Indiana.

Casas’ inclusion in the exhibit Robert Indiana: A Legacy of Love, which opened on October 15, 2020 at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, is unusual. The McNay Director, Dr. Richard Aste and art curator Rene Barilleaux have determined to assure that the McNay presents a diverse representation of contemporary artists. The exhibit includes stunning works by Indiana, the creator of the famous LOVE sculptures, as well as prints by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

The “Love” exhibit, which featured more than 75 paintings, prints, sculptures, costume designs, and digital artwork, also included San Antonians Chuck Ramirez, and Jesse Amado, as well as Californians Ester Hernandez and Richard Duardo. In the past three years the McNay has presented two Richard Duardo exhibits.

Robert Indiana’s first show at the McNay Museum of Art occurred in1968, thanks to the famed patron of the arts, Robert Tobin, who donated a number of Indiana’s works to the young museum. It is fitting that significant and prominent Latino artists’ work is now included in this important pop art genre.

The Mexican Influence on Chicano Art